Halldór Úlfarsson Interview

"There is a kind of magic to feedback"

Feedback is fundamental. It brings life to otherwise static systems, introducing a balancing act of change and adaptation umbilically linked to the amplifying or stabilising forces of its inputs. When used in musical instruments, the musician becomes the system’s guide, not as master but rather as equal participant.

Halldór Úlfarsson’s halldorophone gives us the chance to engage in the loop, tailored to the “tactile perception” of the human experience. While we can study and perceive feedback in nature or mathematics, here we can reach out and touch it.

No wonder then that the halldorophone has become an object of fascination. By amplifying the vibrations of a cellos’ strings, it generates a distinctively stirring yet unstable sound that calls out to composers and musicians. Its inherent appeal has been fuelled with considerable oxygen from high-profile use in Hildur Guðnadóttir’s Academy Award-winning score for Joker and recordings from drone metal lords Sunn O)))—rarely does such an innovative new instrument reach such broad attention.

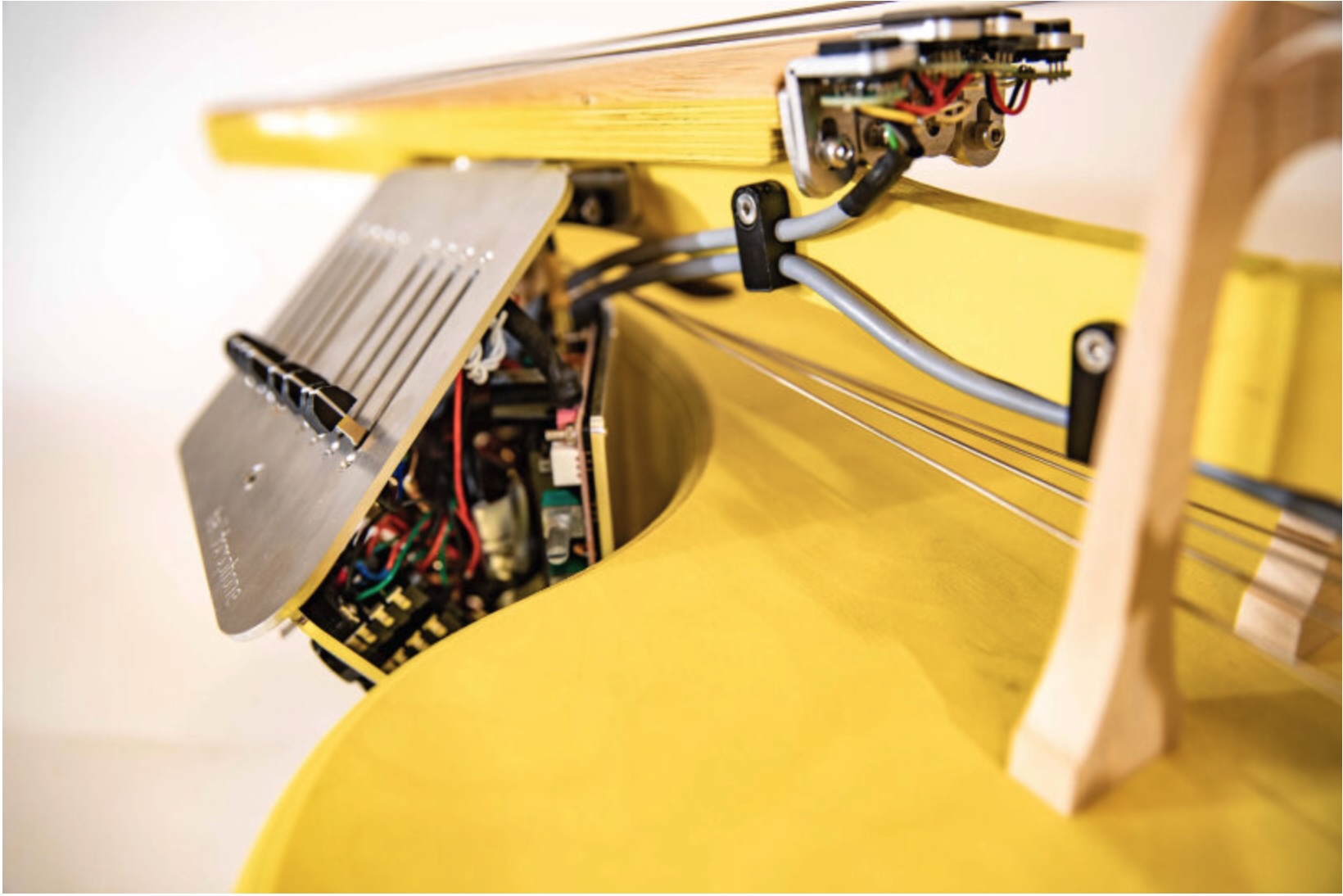

Various iterations of the halldorophone have been augmented by the Bela Mini, introducing a ream of new possibilities that can either invisibly support the instruments’ inherent properties, or open a Pandora’s Box of real-time digital processing. In conversation with Úlfarsson, we unpack the questions raised by introducing embedded computing to the halldorophone: do we disappear behind its existing character while providing increased stability and performance options for the user? Or use it as a starting point for DSP-based composition? We also cast an eye on the various processing techniques being explored by halldorophone users while covering the development of its fabrication over time and the ideas underlying its evolution and ideas.

Halldorophone 2024 model

You’ve always said that you came at music from “the outside.” In the formative period before and as the halldorophone was taking shape, what was your “inside?” Product design? Art?

It’s a blend. I studied fine art in Helsinki, Finland, from 2003 to 2006. So I enrolled in the Academy of Fine Arts, which has now changed name. There was a department called Time and Space, which I was enrolled in, which basically is a fancy way to say new media, including video art, performance art and sound-based art.

So the palette of materials, methods, and inspirations was big. We had sound artists, experimental musicians and visual artists interested in sound art tutoring us. I like to say that I was not a very good art student, which is maybe not entirely true because I was kind of active and tried a lot of things. There was also a very lively experimental music scene in the city at the time with a healthy overlap of people between the Sibelius Academy. This is the Academy of Music, the prestigious one, and it had a small number of experimentally minded, open-minded composers and players who wanted to do something off the beaten track.

Halldór Úlfarsson

It’s hard for me to fully connect with how musicians scaffold their knowledge. I don’t really have any good sense of musical structures or patterns. But when I played with feedback, it was a stream you could modulate. It takes away the personal responsibility of having to know how to think and plan musically. Then if I involve strings, I have something tactile and inherently musical as the string feedback almost always sounds harmonic.

Musical instruments hold a kind of power. And if your intention is to capture attention and imagination, the narrative surrounding them beyond their function or musical usefulness is very strong. In the beginning, there was this idea of creating something that looks and feels considered, as a “real instrument,” to see if I could pull a fast one and get composers and players to engage with it as such. So I realize that has a cynical twist to it, which is no longer the case. We can almost call it performance art, the game I was playing. If I could sneak something in, create this flurry of engagement and create this, I don’t know, like a theatre of a new instrument coming into the world. But quickly there started to come in little confirmations that feedbacking strings are of real interest to musicians which walked me away from that almost cynical intent.

I have come to realize there is a kind of magic to feedback in that it feels almost natural. It almost mirrors complex systems and how ecosystems behave. Nature has voluptuous examples of positive and negative feedback loops on a micro and macro scale. But we don’t perceive them so immediately in our human experience and especially not bracketed to our kind of tactile perception, like something immediate you can feel and shape. The halldorophone and other feedback instruments, I think, benefit from this—there is an underlying logic that is weirdly familiar and make an interesting premise for musical instruments.

How do you get from this point to being involved in instrument and product fabrication?

As the halldorophone became the project I was most interested in, I enrolled in a second master’s program which was called Applied Art and Design in another university in Helsinki (TAIK which is now part of Aalto University). This was based on the understanding that for the most part, centimetre accuracy in terms of fabrication is good enough for visual artists, but instrument designers need to think in millimeter and submillimeter accuracy. So I enrolled in this program to focus on developing the halldorophone.

Yellow series of the Halldorophone

That was a product design course with fairly open-ended parameters, intentionally flexible in the kind of projects accepted. People focused on different materials and methods. To summarize I took my, let’s say, self-taught skill set of fabrication and design and stepped into a more formal environment where I could up that sensibility. So fabrication became a part of how I thought about the instrument, how to make material choices and work on it. Another potential path would have been to enrol in a more traditional lutherie course, but I am pleased with the choice to acquire a more general design skillset.

It appealed to me to use digitally assisted tools and a variety of materials. Looking at the halldorophone now, you’ll see that it has details in industrial materials. Aluminium paneling with a nice kind of origami touch and other modern materials, stainless steel for the pin and part of the nut for the upper strings, etc. The part of my working life where I became the fabrication tutor for the Design Department at the Icelandic University of the Arts was based on this skillset. I’d moved back home to Iceland and needed a stable income and an environment to continue my own work. I was hired because I had focussed on CNC and 3D modelling. It was around the first real intentional push in that school to involve 3D printing, laser cutting and CNCing in the workflow for students. So I built the then new workshop with this in mind, developed a curriculum to standardize workflow between CAD and CAM and did that for five years.

Fabricating halldorophones

In the last years you’ve developed a workshop in Athens—is it based purely around making iterations of the halldorophone?

Yes. Around the time I bought the workshop, Hildur Guðnadóttir created a big splash in popular media. That gave the halldorophone a very favourable wind, which gave me the opportunity to fast-track development with repeatability in mind and build that workshop. It became easier to get grants. Some commissions came in.

I would say that I probably spent around four years doing more work than I did in the previous 10 years in that workshop. Previously, the halldorophones I had built were very much one-offs. My blind spot on this project is that I’m not strong in developing electronics. So I found a collaborator who I have developed the electronics with since then, Orfeas Moraitis, who is an in-house developer for Dreadbox in Athens. Then I also found the luthier, Konstantinos Tsopelas, who builds the sound boxes for the halldorophones.

I’m curious about the initial decision to bring DSP into the halldorophone. If I’m reading between the lines of some of your earlier interviews, it seemed like you were well aware of how digital processing can undermine the immediacy or comprehensibility of an instrument. How did you find a balance between exploring the possibilities of digital augmentation without compromising the halldorophone’s soul?

It’s a good question. The halldorophone is a moving target in terms of features and organisation around the core function of feedbacking strings. It has this, let’s say, novel twist on the ancient interface of strings, which are an exceedingly old musical interface for humans. Strings appear in many kinds of patterns of instruments, including in terms of tuning and ergonomics, but regardless. The halldorophone presents something new having the premise of being an instrument for feedbacking strings.

In the early days, musicians would assume it’s a cello-like thing. But then they would find that, if you approach it from the perspective of a cello, it impedes your intent. The feedback is not very linear. It’s contingent on the given setting, even atmospheric pressure, the room you’re in, et cetera. So they realise they have to react to it. The feedback becomes this thing that they negotiate with. This is a core function that is central to the halldorophone.

So by staying a little bit conservative and skeptical of the potential new control functions that early users would suggest, often DSP, even if I was not super conscious of it in the beginning, the driving intent with the halldorophone became about almost puritanically distilling feedback as the core identity of this thing. There were many undoubtedly good ideas about what new functions could be useful. But that’s why, for example, I didn’t develop an EQ for each channel representing a string or the master mix.

Yellow series of the Halldorophone with Bela Mini

Once me and Orfeas started the development push together we created a simple breakout function. So in the newest models, you can break out the clean signal of every string at line level. You can take that into an audio interface, mixer, or whatever, which gives you further mixing possibilities for live performance or recording. It also gives you the possibility of introducing your own DSP, if you so choose. So we leave it open, not prescribing any DSP as a core function but giving you options to implement what feels useful.

In the latest halldorophones you also have two mix groups (with every string assignable to one or both), which you could, for example, route into two pedals that then come back into the instrument to complete the feedback circuit. Ergonomically, this is a kind of low cognitive load method to organize control over the eight string total. It also leaves your fingers free, which means you can bow, fret, pluck, and let your feet take care of the thinking about how intense the feedback is. This then also becomes an easy pathway for DSP experiments (pedals and such).

With the Bela being a wonderful prototyping and invention tool, it allows you to do stuff fast and at low cost. You’re not building circuits. You’re not adding hardware. You have this wonderful little brain in there. We now have a “research halldorophone” at the Intelligent Instruments Lab with a Bela onboard and in that very rich environment of people who have the mindset and technical ability they can very quickly make halldorophone compositions using some little DSP tweaks that they’re interested in and just try them immediately. And that’s wonderful.

Chris Kiefer with an augmented cello

There’s a paper you authored with the composer and double bassist Andrew Pultz Melbye about augmenting a feedback double bass with a Bela, which eventually became the FAAB (feedback-actuated augmented bass). How did this process of building a cohesive relationship between digital processes and feedback play out?

Adam and I met in the kitchen of a neighbour after he slept off a gig the previous night somewhere in the UK. We started chatting and we kind of realised that we had a lot to talk about.

From my side, I always had the thought that feedbacking strings would sound great on a double bass. But the size is prohibitive so I went one size down to the cello to inform the pattern for the halldorophone. So Adam and I start talking and we decide to collaborate and got a production grant to build an instrument. The instrument is inherently Adam’s—there’s been like a couple of iterations and he’s continued developing the electronics and the code.

So I modified the bass to house a speaker cone in the back of the sound box and Orfeas built a power circuit for feeding the Bela and the power amp. We plop in a little control interface with a slider per string. But from moment one, the idea is this was to be a hybrid, electroacoustic digital instrument. Adam has never, to my knowledge, been interested in playing it without a DSP. It’s totally ingrained in how he plays it, how he thinks about it, how he composes for it. And the thinking behind the DSP is all his. His coding skills and way of thinking are absolutely the heart of that instrument.

So this is where automatic gain control and adaptive filtering come into it. What other techniques have composers been using when working with the halldorophone?

For example. My colleague at the Lab Victor Shepardson threw together a composition recently—he didn’t really want to name it, he felt it was insignificant, but it’s super good. In his words, it’s a homeostat. So it kind of monitors the gain of each of the strings. And if the gain goes high on one string, which means that the feedback wants to settle in a high resonance and become kind of predictable and dull, it knocks down the gain on that string and picks out another lower one and turns it up. So in this dynamic system, it creates this nice kind of flowing, droning harmonic feeling that stays pleasantly evolving. It doesn’t get stuck in like something super predictable, and it’s not very aggressive.

As you said, dynamic filtering of various kinds, or any type of gain control is so integral to the feel of the feedback, how it flows and crescendos and ebbs and flows. Monitoring how the power hones in on certain frequencies. Pitch tracking and transposing has been something to think about, too.

Thor Magnussen had this idea that bandpass filtering may allow us to jump between harmonics that want to feedback. Our colleague Federico Visi spent two months at the Lab with his own interesting string instrument called the Sophtar, which has many functions built in, including a little feedback transducer, smaller in power rating than what the halldorophone is rocking. He caught this idea on the fly and built it in.

It was a weird moment of synchronicity because one of my old friends and colleague of ours at the Lab, Davíð Brynjar Franzson, who is a Los Angeles based composer, started working with the same idea at the same time. He’s been working with the halldorophone for years.

And so this very simple trick of bandpass filtering to focus on harmonics seems like a powerful, fruitful thing to build in.

So having a bandpass filter in the feedback loop extends upon the possibilities of something that’s already happening natively in the instrument.

Right. So instead of just passing the string directly into the main mix that perpetuates the feedback circuit, you bandpass to bring certain harmonics to prominence. It gives you a creepy amount of control over the harmonics. So that’s something that I have thought about adding to the control panel of the Lab halldorophone. We would build a circuit and then give you some sort of control through and addition to the interface, possibly with Bela’s Trill sensors, which I’ve been curious to tinker with but have not had the time. It’d be something that would allow you to do the gain mix and choose a harmonic setting with some visual confirmation of which harmonic you want to bring out per string.

I’d say out of all of these kinds of experiments, some of which would fall squarely in the category of compositions implemented as code, this feels like a function that is germane to this kind of instrument and would be worth adding to the interface. Purely because it relates to a real, physical thing, the natural vibrational modes of the strings.

Huge thanks to Halldor for the interview. See also our previous blog post on the Halldorophone: https://blog.bela.io/halldorophone/.