Sjoerd Leijten Interview

"You can't look away from sound"

The instruments and sound installations of Dutch artist Sjoerd Leijten emerge from the friction between experimentation and environment—between sound and the structures that shape it, whether social, physical, or conceptual.

Trained as a composer but drawn to the raw immediacy of DIY electronics, Leijten’s instruments and sculptures take many forms: bicycles repurposed as sonic machines, watchtowers transformed into resonant chambers, and wearables that translate electromagnetic waves into sound through movement. In short, his practice continually challenges how and where music is made and experienced.

Here, he discusses sculpting soundscapes in fjords, the technical underpinnings of wearable instruments, and how tools like Bela have become not just components but collaborators in an evolving dialogue between body, space, and signal.

Sjoerd Leijten.

Tell us a little about your background. Where are you from, and when did you start making music? How did your interest in creating instruments and installations develop?

I’m originally from the Netherlands but based in Antwerp. I studied music composition and technology at Utrecht School of the Arts. Initially, I focused more on score writing. While I took classes in C++ and SuperCollider, I wasn’t particularly interested in programming at the time. It was only after graduating that I started integrating electronics, particularly SuperCollider, into my practice.

A pivotal moment was attending an intensive SuperCollider workshop with electronic musician Jeff Carey. Around that time, while living in Amsterdam, I started experimenting with turning bicycles into instruments. We used a Panda Board and an Arduino to translate the speed of bicycles into sound and visuals, creating a radio-based proximity sensor for the bikes. This evolved into Volle Band (which means “full tire” in Dutch), an artist collective organizing guerrilla bicycle performances and expeditions. The project combined screenings, performances, and art interventions across Amsterdam, with bicycles functioning as mobile PAs for musicians and a cargo bike carrying projectors for site-specific visuals.

This experience revealed the possibilities of artistic DIY strategies, electronics, and electroacoustic music within urban environments. We often performed under train viaducts, incorporating surrounding city sounds into our compositions.

When did you first start using Bela?

I came across Bela about four or five years ago. Initially, I experimented a little but was still using Raspberry Pi for another project. It was really with Watchtower that I started using Bela more seriously, and later with Aether Arcer. Now I’m also using Bela in a project called The Booth, where we installed a phone booth in schools. Teenagers step inside, respond to playful question prompts, and have their voices resampled in real time. Bela acts as a sampler, slicing their voices and playing them back over a rhythmic beat. The software detects onsets—the moments when a word or sentence starts—and aligns them with a beat to create rhythmic compositions.

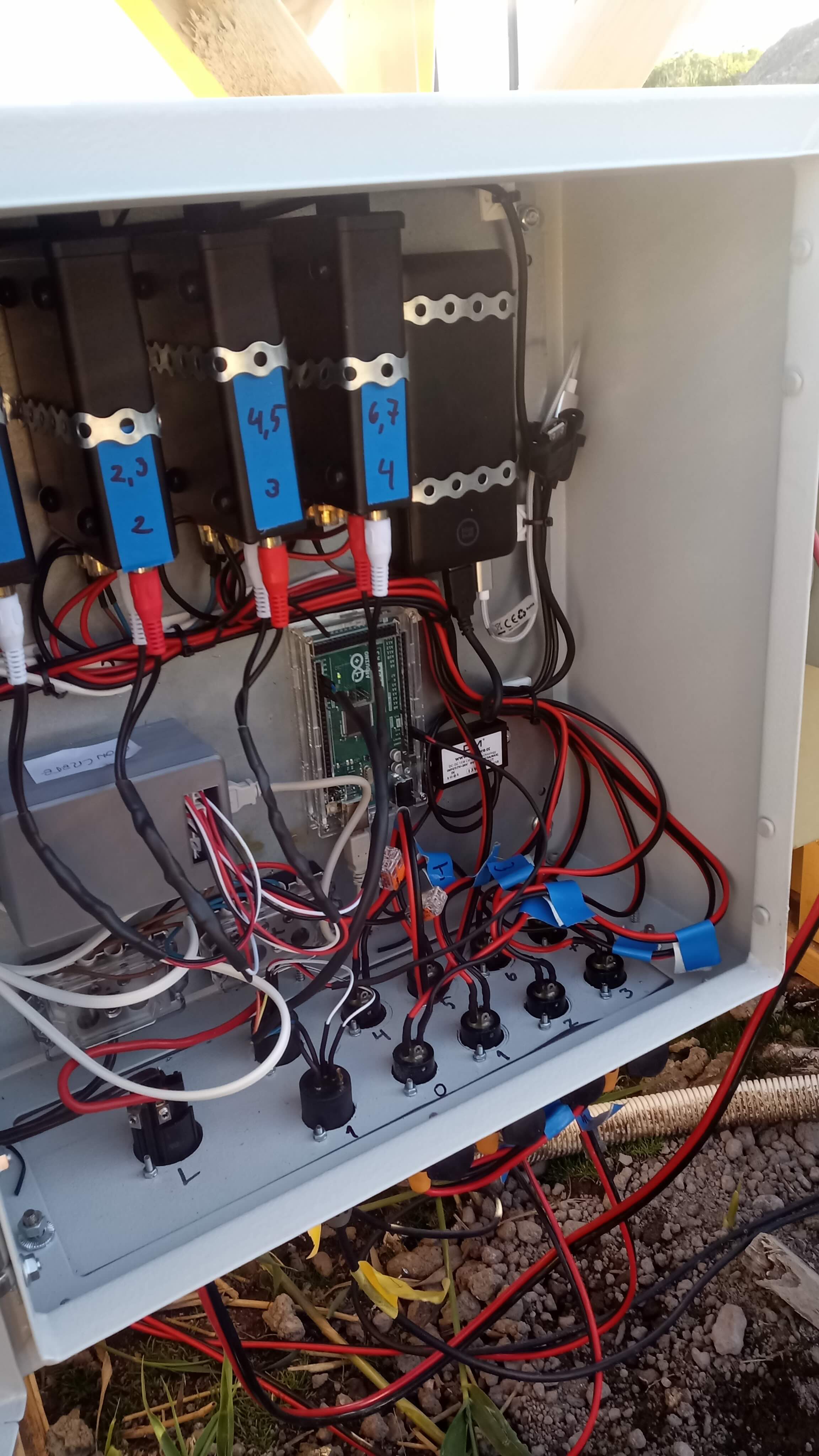

Left: Watchtower. Right: the inners of Watchtower including a Bela board.

Let’s talk about Watchtower. What is the project, and how does Bela fit into it?

Watchtower is a series of sound installations in a landscape, a collaboration with artist Johannes Bellinkx. The first installation was in Fredrikstad, Norway, designed as a hiking route with seven installations. A new version is set to be presented in Copenhagen, Denmark later this year.

Watchtower installation focusing the listener on the trees above.

Each installation detects a person’s presence and triggers an 8-channel composition. Exciters positioned close to the ears create intimate, tactile vibrations, while bass resonance speakers in the supporting beams add a bodily sensation of low frequencies. Additional speakers hidden in the landscape subtly blend artificial and natural sounds, such as FM synthesis mimicking seagull calls, ensuring a seamless acoustic integration.

Watchtower installation focusing the listener on the lake.

Thematically, the project questions traditional watchtowers, which symbolize human dominion over landscapes. Instead of looking over the landscape, these installations immerse the listener within it, often nestled in reeds or bushes. The installation site was a fjord next to an artificial island made from waste, part of a circular waste-processing facility—a juxtaposition between industrial development and pristine nature.

“You can’t ‘look away’ from sound. Our installations played with this, directing attention toward industrial sites while overlaying natural sound elements, subtly questioning how we perceive and frame our environment.”

Deepening connections with space is central to your work, especially in your wearable instrument Aether Arcer. How did that project come about?

Aether Arcer is a collaboration with wearable sculpture artist Daphne Karstens and stems from my fascination with radio and electromagnetic signals. I’ve worked with pirate broadcasting, own a collection of FM transmitters, and previously developed a radio beacon project that transformed electromagnetic signals into music in real time.

Inspired by Salomé Voegelin’s concept of “sonic sensibility,” I started thinking about “electromagnetic sensibility”—how these invisible, inaudible signals can destabilize our perception of the world and reveal new possibilities. Aether Arcer became a way to physically interact with electromagnetic waves, using granular synthesis and microtonal tuning. It’s a form of both embodied listening and embodied composing.

Sjoerd Leijten performing with Aether Arcer.

Why did you choose granular synthesis and microtonal tuning for this project?

Initially, I considered presenting raw electromagnetic sounds, but as a composer, I naturally wanted to shape them. Granular synthesis allows me to manipulate tiny fragments of sound in real time, while microtonal tuning creates a structured yet expressive musical dialogue between the performer and environment.

Sjoerd Leijten performing with Aether Arcer.

How did you collaborate with Daphne Karstens on the design?

I started with basic e-textile experiments using Trill Craft. While I could prototype the electronics, I needed a professional designer to refine the aesthetic and ergonomic aspects. Daphne helped develop arched flexible PCBs that wrap around the body. We scaled up Trill Flex sensors into large arcs following the body’s natural lines, ensuring both wearability and responsiveness.

Sjoerd Leijten performing with Aether Arcer.

How does movement play a role in the performance?

Though I’m not a dancer, every movement has intent because it directly controls the sound. We’re considering working with choreographers or physical theater practitioners to explore this further.

What are the next steps for Aether Arcer?

Right now, I’m focused on making the instrument more robust for touring. Once that’s done, I want to develop a full performance and explore collaborations with mime or physical theater artists to refine the movement-sound relationship.

For more on Sjoerd Leijten’s Work: https://www.sjoerdleijten.nl/