Stacco interview with Nicola Privato and Giacomo Lepri

It's almost like training your body to 'feel' the algorithm

Nicola Privato and Giacomo Lepri’s instrument, Stacco, merges tactile design with a deep sense for improvisation and aleatoric processes. Drawing on influences from traditional musical instruments and media archaeology, the duo have created an interface that’s both a magnetic playground and an experimental sound engine. Stacco’s design, equipped with Bela’s low-latency processing, provides the real-time responsiveness needed for embedded synthesis and precise gestural control — no computer required. However, connected to a laptop, players can also interact with spherical magnets using neural audio synthesis, navigating an AI-trained multi-dimensional soundscape that responds to touch and movement.

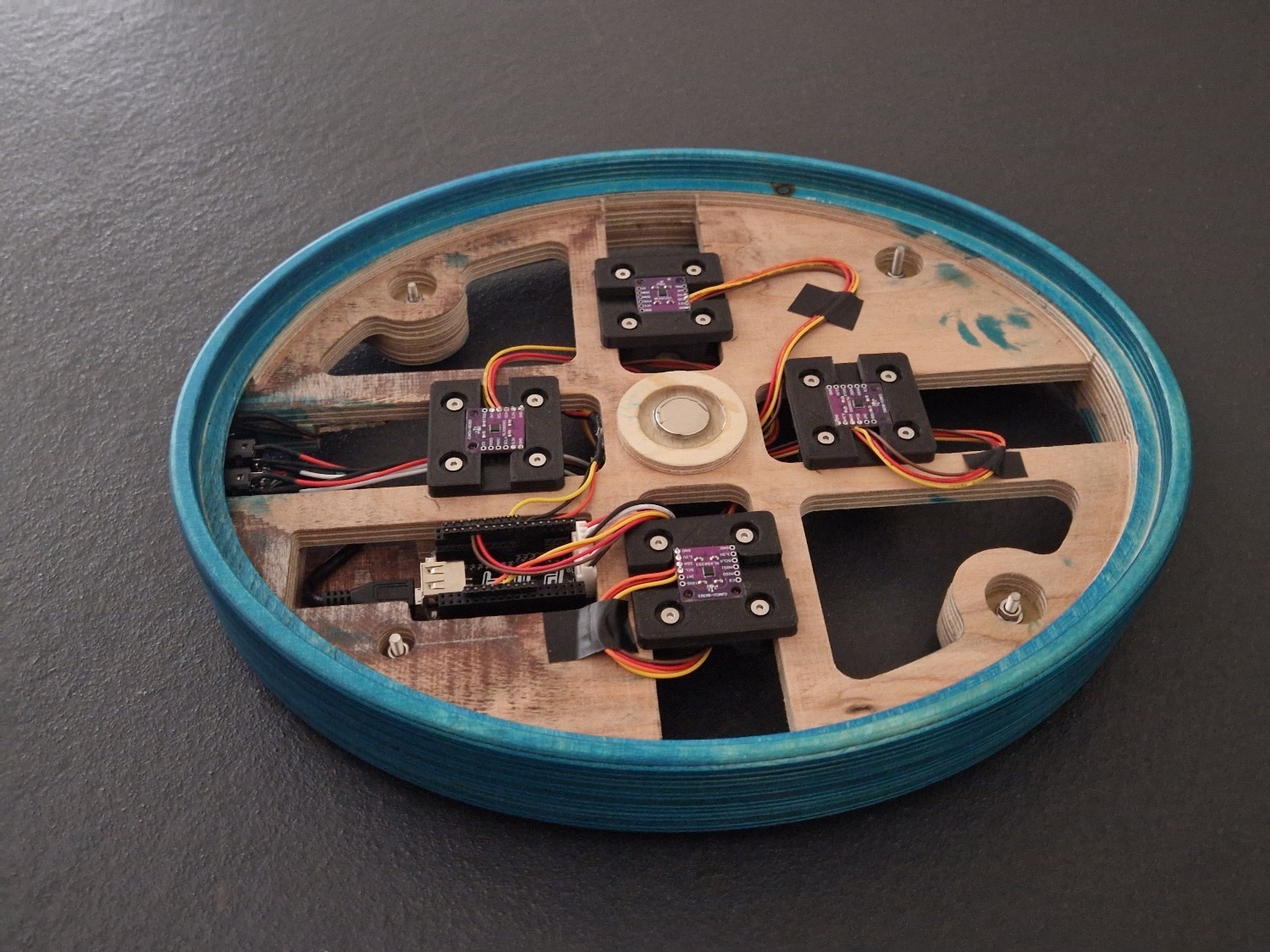

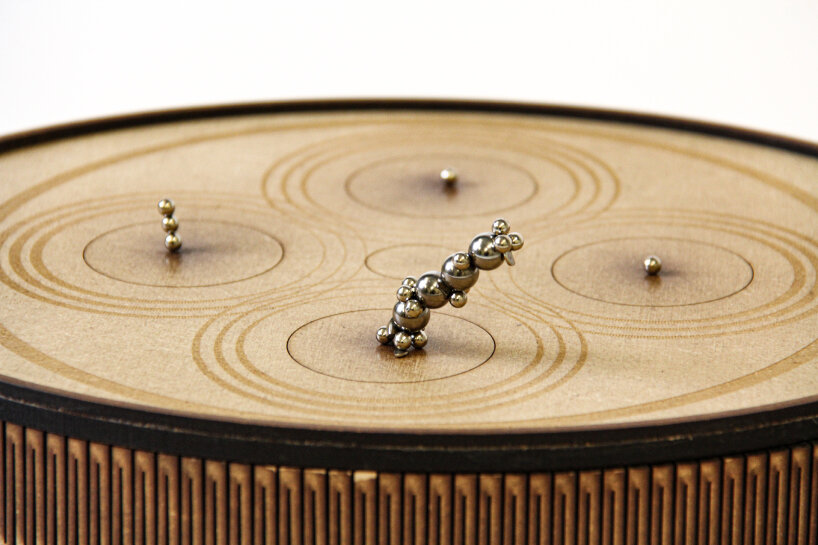

Stacco V1 made from lasercut plywood.

In this interview, Privato and Lepri discuss their journey in developing Stacco, the technology that powers it, and how to let musicians experience sonic complexity as an extension of their own body movements.

Nicola, tell me a little bit first about how you got started in instrument design and what inspired you to explore this intersection between technology, sound, and instrument building.

Nicola: Actually, my background isn’t in design or music technology. I come from jazz. I grew up as a jazz guitar player, running a music school near Venice, Italy, doing gigs for more than ten years. That was my path, but I started feeling a bit bored. Then COVID happened, and there were fewer options to play gigs or organize concerts. I had about two years of free time, and since I couldn’t play with other musicians, I thought, “Okay, I’ll try to make some software to play with.” So, I created a simple AI model to perform with, and the feedback was positive. That led me to study electronic music composition, and then I saw an opportunity with the Intelligent Instruments Lab, who were looking for people interested in this area. I applied, got accepted, and that pushed me further into a different way of thinking about music, notation, and instrument design.

Most jazz usually has fairly fixed parameters for improvisation—scales, harmony, dynamics—but improvising with electronic instruments has completely different parameters. Was there any feeling of having exhausted the parameters of improvisation with acoustic or electric instruments?

Nicola: In a way, yes. Jazz is also a very saturated, competitive, and underfinanced scene with more limited opportunities. I was also noticing that I was repeating myself in my playing, so I felt the need to step back from the guitar. Approaching electronic music opened up a different world. At the same time, computer music often doesn’t have the immediate visual feedback or gesturality you see in traditional instruments. So my approach became about bringing gesturality back on stage. With Stacco and my other instruments, the relationship between sound and gesture is very immediate and extemporary, which is something that comes from my jazz background.

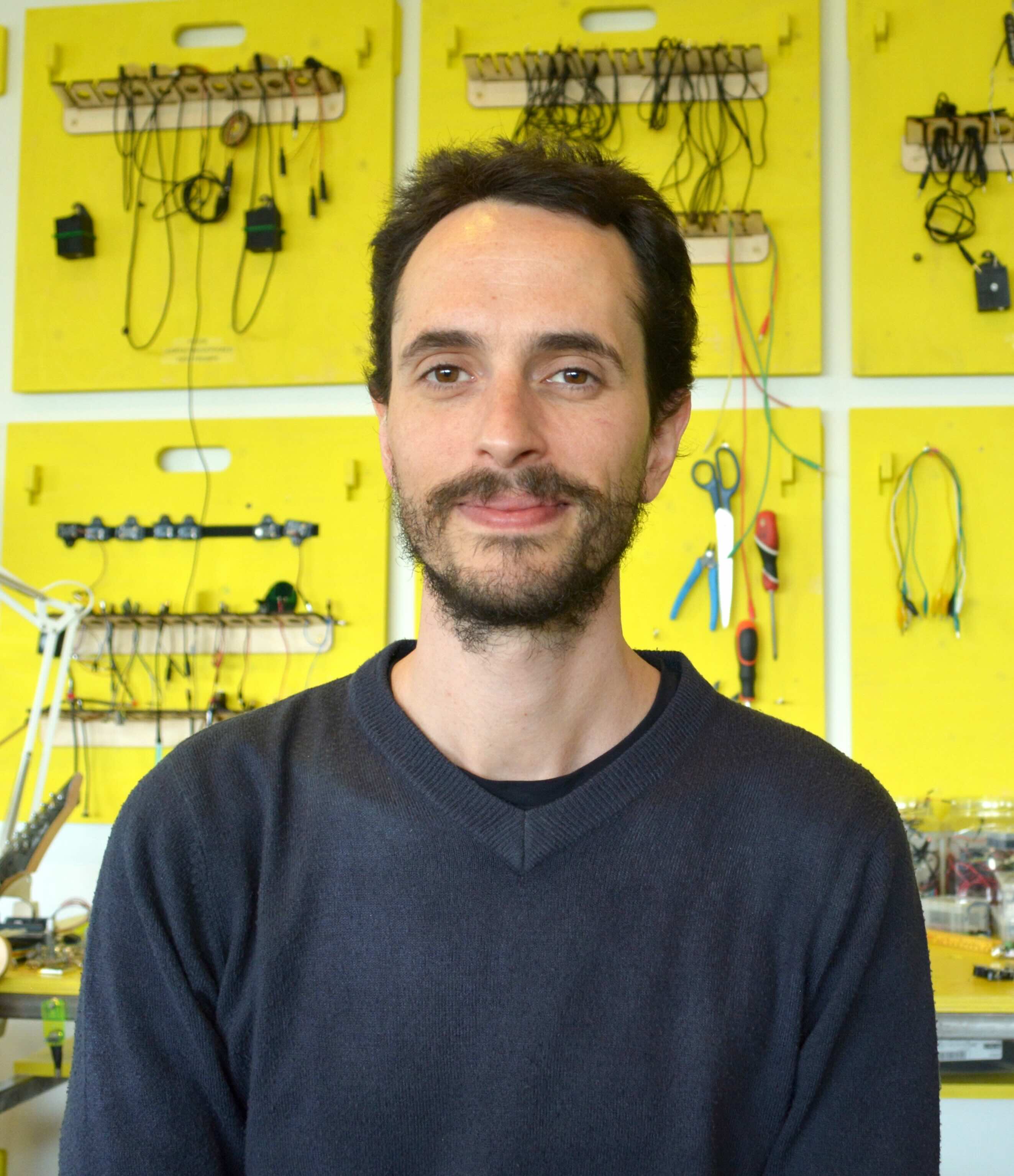

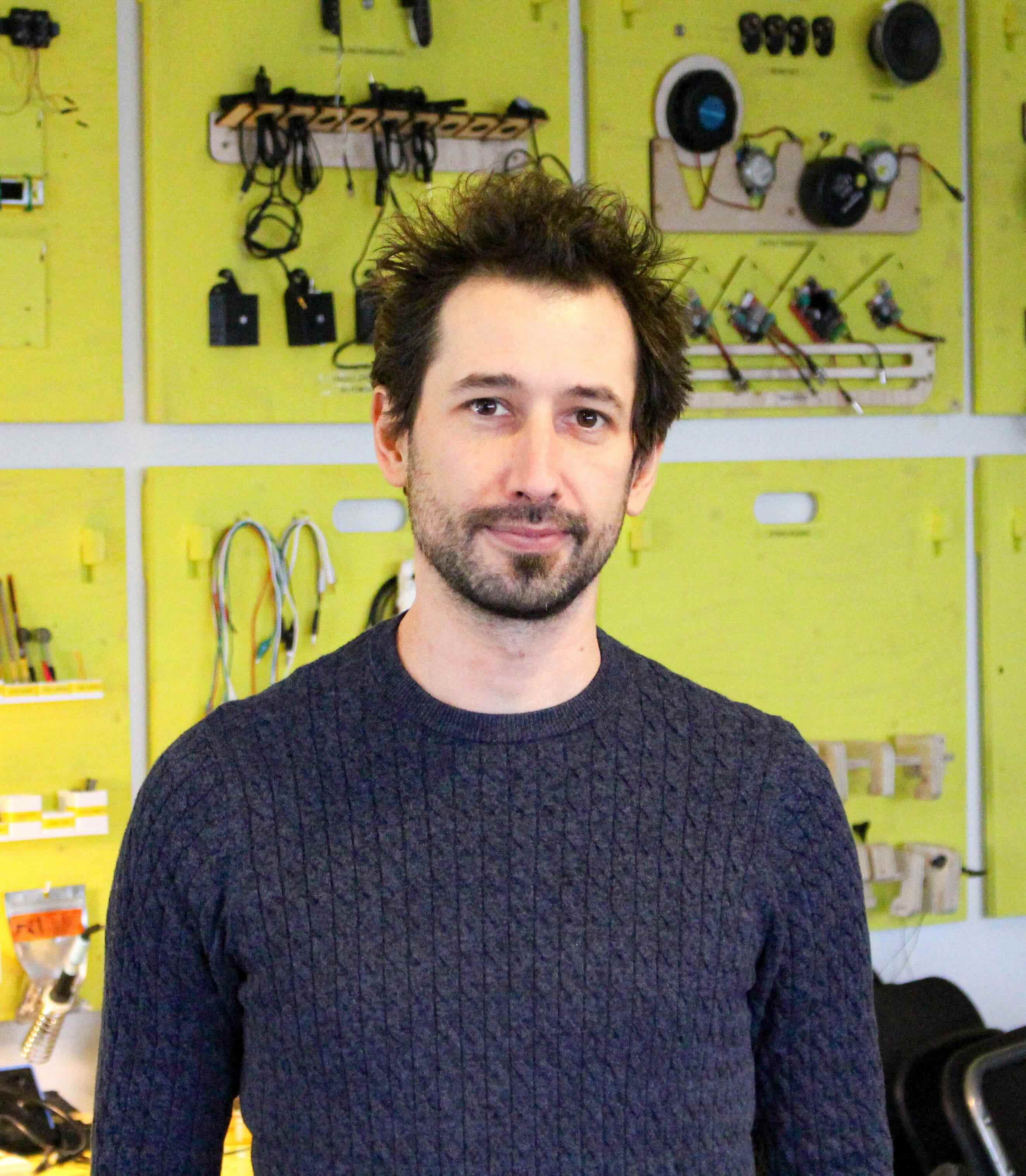

Giacomo Lepri and Nicola Privato in the workshop of the Intelligent Instruments Lab in Iceland.

Giacomo, can you share a bit about your background and how you came to design instruments?

Giacomo: I guess I share a lot with Nicola in that I started with piano and got deeply into jazz improvisation. Through jazz, I discovered free improvisation and electroacoustic improvisation. Electronics came into the picture when a friend suggested I apply for an electronic music course at the conservatory. At the time, I was based in Genoa, Italy, and it was one of those “what do I do with my life” moments. So I started studying electroacoustic music in a very traditional context – Stockhausen, John Cage, that kind of thing.

In time, I realized I needed real-time elements, like in jazz, where you’re living in the present. Composing in a studio and then playing a fixed piece just wasn’t my thing. Through that journey, I eventually found my way to digital musical instruments. A significant turning point was my time at STEIM were I did a master joint with the Institute of Sonology. That experience shaped my direction, solidifying my interest in building instruments that I could play and critically engage with. Another crucial experience was my PhD at the Augmented Instruments Lab where, on top of my artistic work, I started examining the social and cultural implications of new musical interfaces.

It makes sense that you both come from a jazz and improvisational background considering the strong improvisational and aleatoric possibilities built into Stacco. Can you talk about some of the early projects or experiments that led to the design concepts you’re exploring with Stacco?

Nicola: I like to think of Stacco as a hybrid, where my take on playing with magnets meets Giacomo’s. We both somehow ended up working with magnets. Before Stacco, I created an instrument called Thales, which also used magnetism but in a more tactile way. It involved two controllers with magnets facing each other, repelling each other. So when you try to join the controllers, you feel this kind of invisible interface—an emergent phenomenon from the magnetic interaction. That experience fed into Stacco. It’s also where the idea of “magnetic scores” came in—scores where you interact with magnetism as a kind of notational layer. With Stacco, we took that idea further, where you can throw magnets at it, and they attract, allowing you to manipulate a three-dimensional space. Stacco has four of these elements inside.

Giacomo, how did you bring your own approach into the design of Stacco?

Giacomo: For me, it started with an instrument I created called Chowndolo, which is based on a pendulum augmented by magnets – a kind of tribute to the composer John Chowing with references to the work of William Forsythe and Takis. It creates these weird oscillation patterns that are somewhere between chaos and control. It’s visually striking, with tiles you can place under the pendulum to create patterns, almost like a score. I was also inspired by the field of media archaeology, which looks at the origins of media, in this case the pendulum as one of oldest devices conceived to measure time. I mean, isn’t a metronome just an inverted pendulum?. Also, electromagnetism is fundamental to all electric devices, and working with it lets us rediscover that core technology, turning the invisible into something tangible.

With Stacco, Nicola and I didn’t set out to work with magnets together; it just happened. We both shared a history working with magnets in musical settings, and when we met at the Intelligent Instruments Lab we shared a fascination with magnetic shapes. We started exploring spherical magnets and it immediately clicked. Being open to our environment and materials, we were able to create something unique. The spherical form works well because it allows for unpredictable movements, rolling under your hands and interacting with magnetic fields in unexpected ways. It’s an intuitive way to play.

Nicola performing on Stacco.

Stacco is played using a series of spherical magnets, but of course any shape could work. How did you decide on the sphere?

Nicola: It was really a matter of trial and error. We experimented with magnets of very different shapes. For me, the concept of a sphere became central—it was part of my story, in a way. I already thought of Thales controllers and the repulsion between them as a sphere. Even though it was invisible, to me, it was always there, so I was already biased toward that shape. Naturally, it felt right to see that sphere materialize in the instrument.

I think Giacomo had the idea of creating a design with a raised edge all around, so you could throw a sphere and let it roll around, eventually settling on one of the attractors. You can use other shapes, but they don’t work as well; spheres are the most functional and the most fun. They slide under your hands, rolling unpredictably, sometimes interacting with the magnetic fields in surprising ways. So the sphere offers the most engaging and accessible way to play Stacco, but there’s a vast sea of possibilities beyond it.

Another way I found to play with Stacco was by using a magnet embedded in a ring, which repels the attractors inside the instrument. This setup turns Stacco into a kind of theremin—you get close, feel the magnetic field pushing back against your hand, and use that resistance to calibrate your movements. With practice, you start to identify different points around the instrument and can reliably return to them, guided by the repelling magnetic field.

Stacco V1 with stack on magnets.

So let’s talk about Bela. I know that’s part of the instrument construction. Can you tell me why you chose it for Stacco?

Nicola: There are several layers to that decision. When we started, we were at the University of the Arts and had access to various sensors, boards, and other components. We chose Bela because it’s designed for low latency, which was essential for embedded synthesis directly on the instrument. Initially, we considered using a microcontroller, which worked fine to detect data from the sensors, but they didn’t have the computational power we needed. Bela gave us the balance we were looking for — it’s low latency, supports embedded synthesis, and provides audio inputs for DSP.

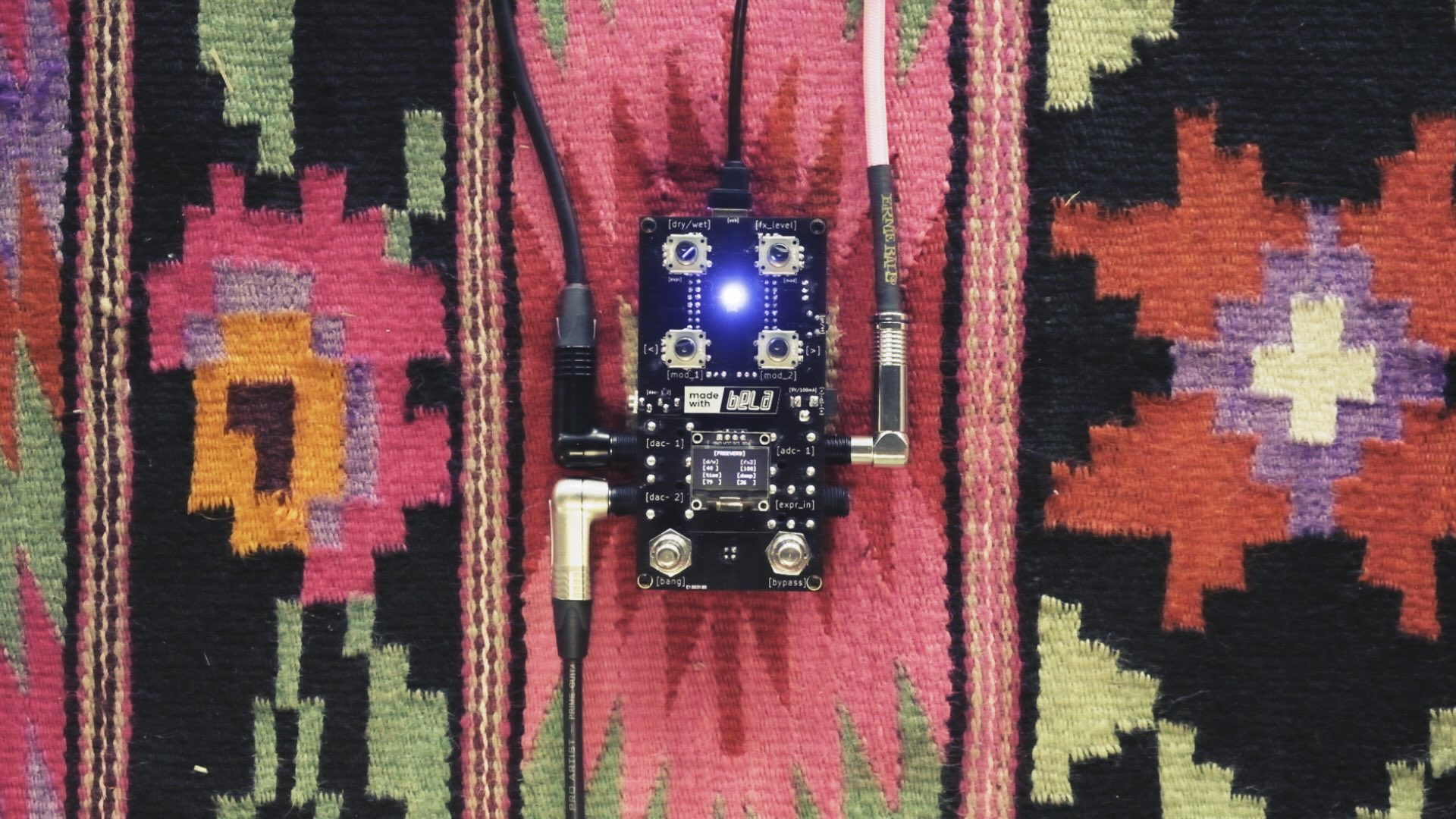

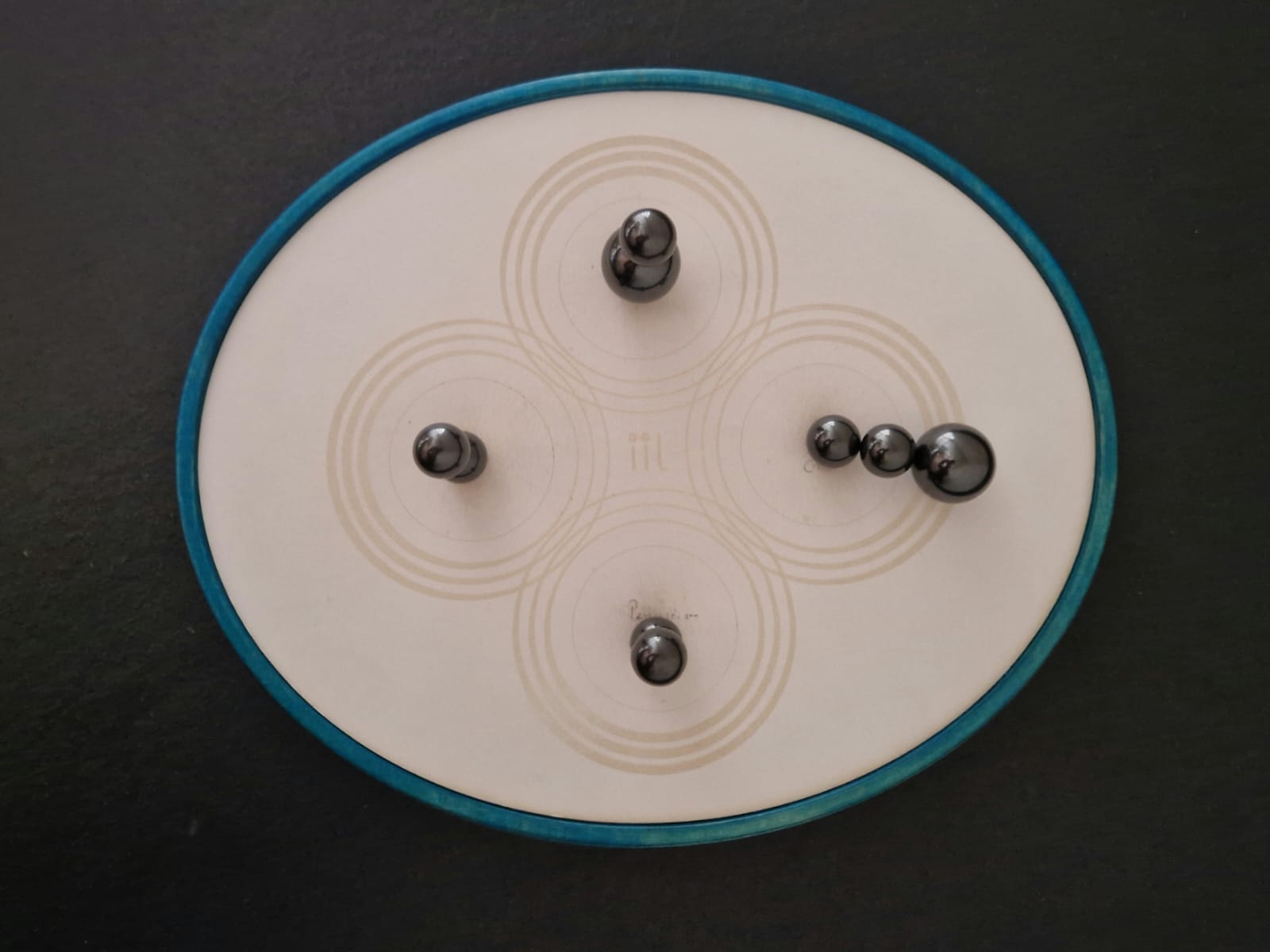

The inners of Stacco showing the 4 hall sensors paired with fixed magnets. The hall sensors output a voltage which changes depending on the surrounding magnetic field and they are connected directly to the analog inputs on Bela Mini which is used for sound generation.

Our first patches used Pure Data. We would do embedded synthesis with an FM syntheser and other simple sketches. But over time, things evolved. Working at the Intelligent Instruments Lab, it was natural to introduce AI into the project, so now we’re using Stacco in two ways: for embedded synthesis on the instrument and by forwarding data to a laptop. For the neural audio synthesis, we forward data to the laptop because Bela isn’t equipped for it yet. If a future version of Bela could handle that, it would open up even more possibilities.

You use neural audio synthesis with Stacco – how does it work?

Giacomo: Neural audio synthesis is a machine learning technique where an algorithm is trained on datasets to identify patterns that we can’t easily see as humans. We use it in two main ways: one is to have the algorithm replicate an existing sound in real-time, and the other is to navigate a complex, multi-dimensional sound space.

With Stacco, we mostly use it in this second way. There’s an entanglement in neural audio synthesis—when you manipulate one control input, it affects the others. This creates an unpredictable quality, almost like the algorithm has a life of its own. You don’t have traditional parameters like pitch or volume. Instead, we built Stacco to mirror this digital entanglement in the physical space, using overlapping magnetic fields that affect each other. It’s about creating a physical interface that allows musicians to intuitively experience these complex algorithms.

Our approach is really about embodied understanding. Instead of trying to explain the algorithm in a rational way, we’re allowing musicians to interact with it physically. It’s almost like training your body to “feel” the algorithm.

Stacco V1, the instrument can be played with all sorts of magnetic objects.

That’s quite different from how AI is often depicted in music these days, where the process is hidden and simplified to deliver polished results. You’re emphasizing complexity and making it sensory.

Giacomo: Exactly. Instead of simplifying the AI, we’re making its complexity accessible to the senses. It’s about using our bodies’ own intelligence to grasp something we might not understand analytically. Musicians already have a kind of physical intelligence from playing their instruments, so we’re tapping into that.

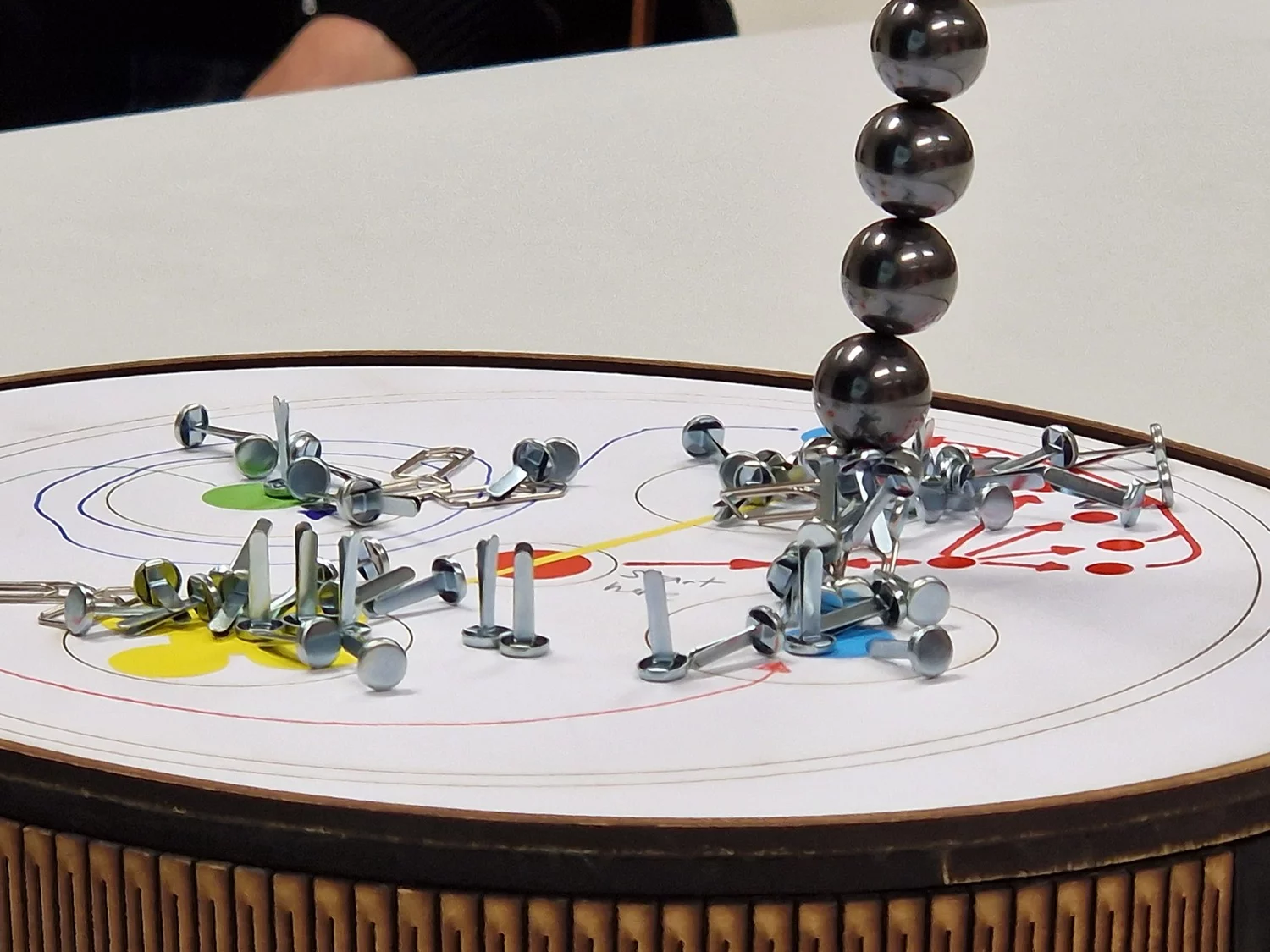

Can you tell me about notation and composition with Stacco? I find it fascinating that you’re incorporating notation directly onto the instrument. Has anyone been able to play from a pattern or score placed on Stacco?

Nicola: Yes, we’ve run a few workshops, and someone could create a clear score, which others were able to reproduce. The temporal element can vary based on the composer’s intent. Some composers want to set boundaries for exploration, rather than dictating specific timings. In that case, it’s more like jazz improvisation within a defined space.

There’s also the concept of “latent space” in AI, where the sound features from a dataset are distributed across a multi-dimensional space. Stacco can help you reach specific points in that space, and a score can act as a guide to navigate those dimensions. This lets musicians explore different “sounds” in that latent space by following the score.

Stacco V2 with 3D printed case.

Could you use Stacco to play classic notation or traditional music?

Nicola: Potentially, you could. It depends on how the sensors are mapped. You might be able to replicate specific pitches, durations, or dynamics, but for neural synthesis, it’s more complex. If the dataset doesn’t include a full pitch range, for example, then you have gaps in the musical scale. Stacco’s strength isn’t in playing traditional melodies—it’s about exploring sound in a non-traditional way.

Giacomo: For me, there’s always this friction. Why build new instruments to play old music? We already have great instruments for traditional melodies and rhythms. I think it’s more interesting to make new instruments for new kinds of music, whatever “new” means.

Stacco as a graphic score.

In terms of production, how many Staccos are out there? Are you making more?

Nicola: Right now, there are three Staccos — two version 1s and one version 2. We’re currently building another for a composer named Robert Laidlow, who’s working on a piece for the BBC Orchestra where the soloist of that piece will be using Stacco. We’re training models on the BBC archives so that Stacco can navigate different orchestral sounds. – strings, percussion etc. It’s an exciting project, and we plan to continue experimenting with the design. Lots of other people are reproducing Stacco on their own – we have a repository on Github so everybody can build it.

Giacomo: We’re still in early stages. Nicola talks about version 1 and 2, but for me, it’s like version 0.01 and 0.02. It’s very fresh – we’re still in the beginning phase.

Have you considered making Stacco accessible for musicians with disabilities?

Giacomo: Not specifically, but it’s an interesting idea. The instrument is very sensitive to micro-movements, thanks to Bela, and the spheres can be moved easily. There’s potential for accessibility-focused applications, and it would be great if someone wanted to take Stacco in that direction.

Nicola: Our focus has been on artistic and technological questions, but Stacco’s openness and fluidity could certainly lend itself to different accessibility applications.

A huge thank you to Giacomo and Nicola for agreeing to this interview and for their generosity in sharing their work. To find out more about their work check out their websites: https://www.giacomolepri.com/ https://nicolaprivato.com/.