Towards Disabled Artist-led Music Technology

Using Bela for accessible music exploration

In this post Charles Matthews guides us through his work in accessibility, education and musical instrument design. He explains how Bela has become a tool-of-choice and shares his thoughts on the future of instrument development in relation to disability. Over to Charles.

Re-examining “Accessible Music Technology”

When the Bela team asked me to write a guest blog post about what I’m doing with the platform, I knew that it wasn’t going to be straightforward, particularly because I believe there’s a message behind most of this work that risks getting lost behind the fancy bleeps and flashing lights! For that reason I’d like to cut straight to the chase and present the essence of this post:

embedded computing is bringing adaptability to instrument development in ways that seemed like wild science fiction only a few years ago, however we need to work harder to open access up. Maintaining an open source approach is one way of going about this as to adapt and extend sit at the heart of access.

Bela in my work

I use Bela on a daily basis and have for the last couple of years. As an embedded computer designed to handle sound, it helps me move from making controllers toward making what I might more readily call instruments: self-contained objects that don’t require an expensive laptop sitting at the side doing all the hard work (and, in some cases, perhaps an implication of someone else operating that). This helps create contexts that de-emphasises screens places the focus on more tangible types of interaction.

A visitor explores an exhibition of instruments created by a group of Disabled students through the Hidden Sounds course at City Lit.

Screens and laptops are absolutely still relevant, as toxic as I might find them myself in situations that demand shared attention. That’s another blog post, perhaps. Maybe it’s more constructive to say that these new instruments afford different kinds of interaction. Less things to plug in (which can mean less barriers to setting something up independently), tactice feedback, and many more options to hand.

Avoiding disability dongles

Technology like Bela is rapidly becoming a key ingredient in making what we could call accessible music technology. It’s commonplace to use “AMT” as shorthand for this (the A is kind of interchangeable between accessible, assistive, or adapted) but I find myself increasingly questioning that label. We could argue that all music technology should be accessible, but in doing so, we run the risk of writing out the direct lived experience and cultural contributions of Disabled individuals and communities. What’s still often lacking in accessible music technology is the direct involvement of the people it claims to engage in the design process. In my opinion, if we approach Access first, rather than compromising with an abstract notion of accessibility, the conversations and inclusion we seek are more likely to take place.

Working within well-intentioned frameworks like Universal Design or Design Thinking, designers often lose their way by making generalised assumptions about accessibility rather than engaging in direct dialogue or inclusion. This can lead to the development of what Liz Jackson has recently identified as Disability Dongles: “a well intended, elegant, yet useless solution to a problem we never knew we had”.

Examples that Jackson has hilighted include gloves that translate sign languages into spoken English, and expensive wheelchairs that can negotiate stairs (I’ve held back on my opinions on equivalents in our scene, at least for now… it’s complex). These are items that place responsibility onto the individual to adapt, rather than addressing issues with the environment or culture — and furthermore push the existing solutions upon which they are based into being perceived as some sort of impairing or confining factor. They’re based on assumptions rather than conversation or direct involvement in the process; Disabiliy Dongles are the result of attempting to approach “accessibility” in abstract.

To avoid this problem, Jackson suggests an alternative to Design Thinking, which she calls Design Questioning (you can find out more through this video presentation and interview). Crucially, she highlights that situations involving a detached kind of empathy on the part of the designers leads to expectations of “design thanking” from the recipients or targets of this process. Along with more direct involvement we are seeking, there comes a responsibility to challenge, to ask the hard questions that are otherwise overlooked or smoothed over.

The “AMT” scene is, of course, prone to the same problems as so-called “accessible” technology at large. Digital instruments bring an immediate and highly adaptable approach to controlling sound. Yet accessibility in this context is still on occasion taken to mean the inclusion of a touch screen, large buttons, or a proximity sensor, while closing off the end user’s control of the functionality of these elements, or worse still, closing off other solutions that work perfectly well. Without dialog, the supposedly liberating aspects of the technology are prone to becoming barriers in themselves.

Inclusive design through direct involvement

In many cases instruments are produced for therapeutic purposes or designed to be operated by people taking roles of facilitators or carers rather than allowing direct control, and these constraints are accepted as the norm. If a device can make a pleasant noise with minimal effort, that’s all too often regarded as a sufficient marker of success. Is this good enough? Perhaps in some fairly specific circumstances, because a very direct removal of that first barrier to engagement can be a way of bypassing cultural gatekeepers, of focusing on the communication and power that noise-making affords. There’s not much point in speculating without asking the musicians themselves. But when the default situation entails compromise, does this really represent the creative potential and voice of Disabled musicians? What other barriers are being created in this process? What of the expression found in years of practicing an instrument? This stuff is often hard, for a reason – access should not always imply easiness.

In the meantime Disabled people continue to innovate and adapt by hacking individual solutions, which all too often end up sitting outside the central flow of development, at times overshadowed by more polished products made by non-Disabled professionals.

Organisations like Drake Music, led by a community of Disabled artists, are beginning to address this situation with statements like “by and with rather than for” at the recent DMLab instrument hacking community relaunch. This echoes the “nothing about us without us” slogan adopted by the Disability rights movement in the 90s, and refocuses activities on the social model of Disability. Drake Music is currently pushing for more representation of Disabled people within the music education workforce, which will hopefully contribute to the reframing of technology as something that it is possible to create and operate directly. Work developed or led by Disabled artists often engages with what we might call the aesthetics of access - a positive recognition of what needs to be in place for an instrument or piece to work, integrated from the start, in a way that does not compromise the experience of the player or audience. Engaging with the aesthetics of access implies a shift away from dominant models or assumptions, and more direct engagement with Disabled culture rather than attempts to fix an impairment or blend in.

So what about this new wave of tools? By providing opportunities for rapid prototyping that don’t require constant attachment to computers nor people that are priveledged to self-identify as “techies”, I hope that technology along the lines of the Bela platform can help pave the way for more musical instruments designed and created by Disabled people. That is to say, “Disabled artist-led music technology” rather than just “accessible music technology”.

I don’t mean to suggest that these two ideas are mutually exclusive, but this is certainly a shift that I’m starting to feel in my own practice. I say this as the person usually identified as the non-Disabled partner in instrument building collaborations (although as a proudly neurodivergent artist, I should say that this is not always the case), and as someone seeking conversations around these issues of access and inclusion — and from engaging with Disabled culture and arts in my more personal experiments.

Bela-based projects engaging with access

Most of these examples have either been developed with the support of Drake Music or have been possible through contact with the DMLab community and hackathon events. None of this happened overnight. I worked on many projects around access over the years (some probably quite questionable) before what will be described below. It was contact with Drake Music, and particularly the collaboration with John Kelly described below, that really changed everything.

The Kellycaster

I’d rather hand over to John Kelly for an introduction to the Kellycaster:

The Kellycaster is a guitar, the concept and initial design of which came from John. It came into being through a process of collaborative design with some essential support from Drake Music (and with a physical form developed by Gawain Hewitt and John Dickinson). The Kellycaster has six strings that feed into a digital pickup. Rather than using the traditional fretboard to shape notes and chords, the Kellycaster features a chord library that John selects and modifies for a given song into a song bank. Then these chords are selected live whilst playing using a MIDI keyboard or similar device. Bela is used to pick up the volume of the strings and map them to chords.

An early prototype of the Kellycaster.

We’d made the initial prototype at a hackathon in a matter of hours, but the development process was not easy or quick by any stretch of the imagination. Trying to guess what was going to work for this instrument only got us so far: it took grit and tenacity on both sides to recognise that certain nuances were not coming through, and to find solutions in playing style or code without compromising the aesthetic.

I had assumed we were aspiring to create a self-contained instrument with an audio jack; something that could plug straight into a guitar amp. Although this is still a shared dream, we ended up maintaining a connection to John’s laptop as an access consideration. Using a familiar interface, John could drop straight into gigging with it, connecting controllers, and setting it up as he would any other digital instrument in his repertoire. The result was radically different from what I had pictured as a coder or hacker, and rightly so. As Donald Knuth once said, “premature optimisation is the root of all evil”.

By half way through the project, I made a point only to work on the code while we were together. It was almost certainly a textbook example of how not to do design in the conventional sense, but it got us to where we needed to be. These processes we worked through together have given us both tools for future projects. And, perhaps most importantly, we’ve come out this still speaking to each other.

John: “we have come so far and the journey continues, our dream now is an instrument with a jack connection to plug straight into an amp and of course implementing the ‘Boogie Bar’. [n.b. for the layperson: this means we’re finally going to replace the biro we have sellotaped to the guitar body with a proper joystick]. You can read a lot more about the guitar and development process on John’s blog and watch a video exploring our collaboration above.

Planted Symphony

This project took place as part of the London Liberty Festival in 2017, and was a collaboration between Drake Music and Arts and Gardens. We had a few R&D meetings, led by artistic programme leader Daryl Beeton and a design group of Disabled and non-Disabled artists, in which we explored some rather outlandish ideas – many of which would have been prohibitively expensive to realise even a few years prior, and most of which made it into the final piece. Incorporating Bela, Raspberry Pi, and Touch Boards meant that we could bring sample players and proximity sensors to an outdoor setting, entirely battery powered and for the most part weatherproofed.

Among the instruments were seed clocks that responded to breath, switches that could be walked and wheeled over to play samples, handheld devices that sang melodies in response to the colours of plants and flowers, and trees with capacitive sensors that sang back when visitors hugged them. These were all applications for which we’d usually rely upon a computer or a hardware sampler, which instead fitted neatly into a cardboard or Tupperware box. They weren’t objects that I would necessarily describe as “accessible” instruments, but they certainly presented a new combination of access options in this context. And they were a key element in an immersive experience through which the audience could engage in a piece of music, decide which area they preferred, and start dialog with musicians and guides on how to participate if the access options didn’t quite fit.

This experience informed a project at Belvue School as part of Youth Music’s Exchanging Notes programme, which we dubbed “music outside the classroom”. Together with young musicians, we ended up dismantling the sampler from Planted Symphony, embedding it in a Lazy Susan, which became a permanent box for the school’s music classes.

We also took similar devices outside for spontaneous development as part of the ImPArt performing arts summit in Remscheid, Germany, last year.

Instrument Maker

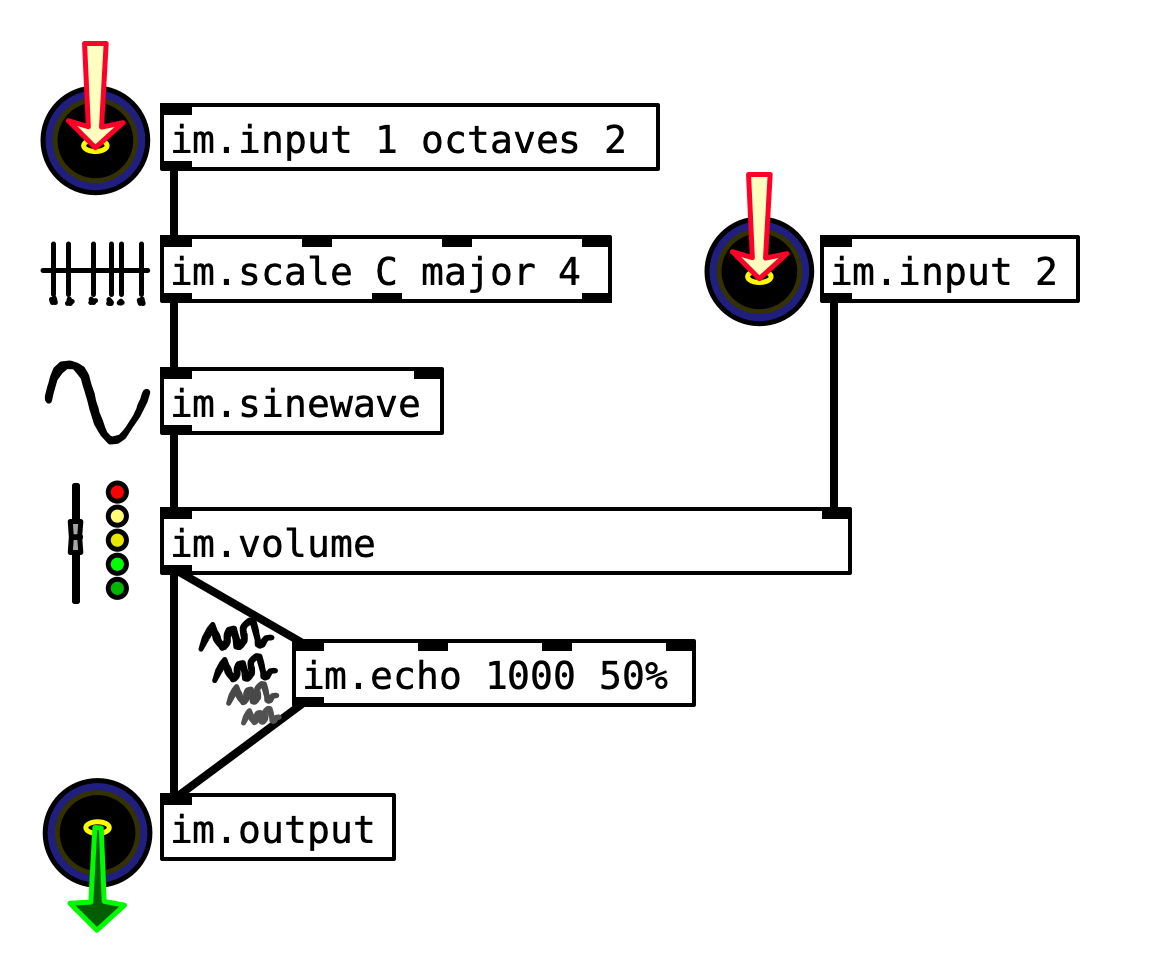

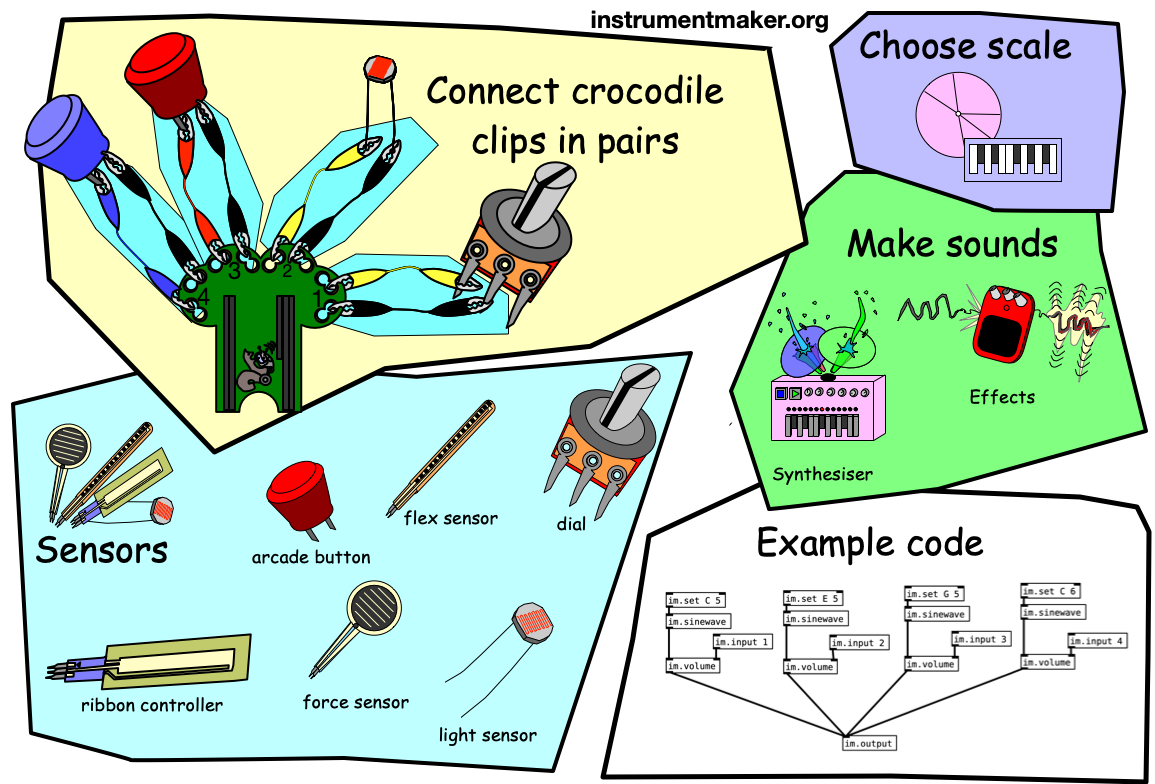

Instrument Maker is a sprawling project designed to open up instrument development. At its core is a library based on the visual programming environment Pure Data. This has expanded to include a set of AAC-style symbols and custom hardware (currently used to adapt… you guessed it… those wonderful Bela boards). It builds upon existing repositories developed in a variety of contexts: instrument building for Drake Music and Wac Arts, teaching in universities, and, of course, those late night experimental sessions for their own sake.

Most significantly, the code for Instrument Maker has come together in collaboration with Gift Tshuma — a professional Gospel musician and Disability rights activist based in Montreal — through our development of a series of workshops to address the pervasive divide between developers and Disabled performers. These will launch at DMLab this October as part of our project “Blurring the Boundaries” (funded by the British Council and Farnham Malting’s New Conversations programme). You can read about our Montreal events with MilieuxMake at Concordia University here.

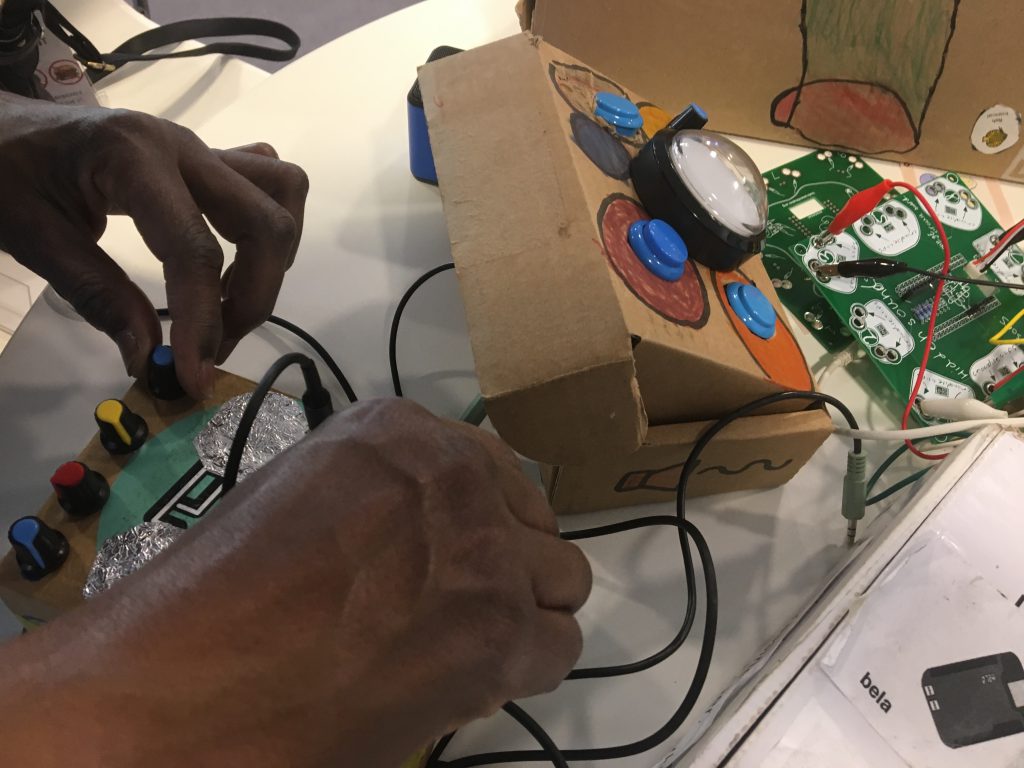

Gift Tshuma (left) and Charles Matthews (right) exploring paper-based technology during a mini hack challenge, with some of the more polished results displayed underneath.

We wanted to fill a gap we’d noticed in currently available resources. During an excited conversation about the potential for enhanced accessibility through “dataflow” programming, Gift challenged me to make a two minute demonstration video of the instrument making process. Of course, I failed — there was just too much to explain to even make a few oscillators play notes from a scale. We went on to discuss how we could develop a set of tools and abstractions to help establish quick, solid introduction.

Our aim is to find a situation where the spark of excitement — the raw potential in that moment in a hackathon or workshop — is led by an even distribution of power for everyone involved. We want to create something to challenge gatekeeping and the existing barriers around assumed knowledge as well as more practical barriers to code.

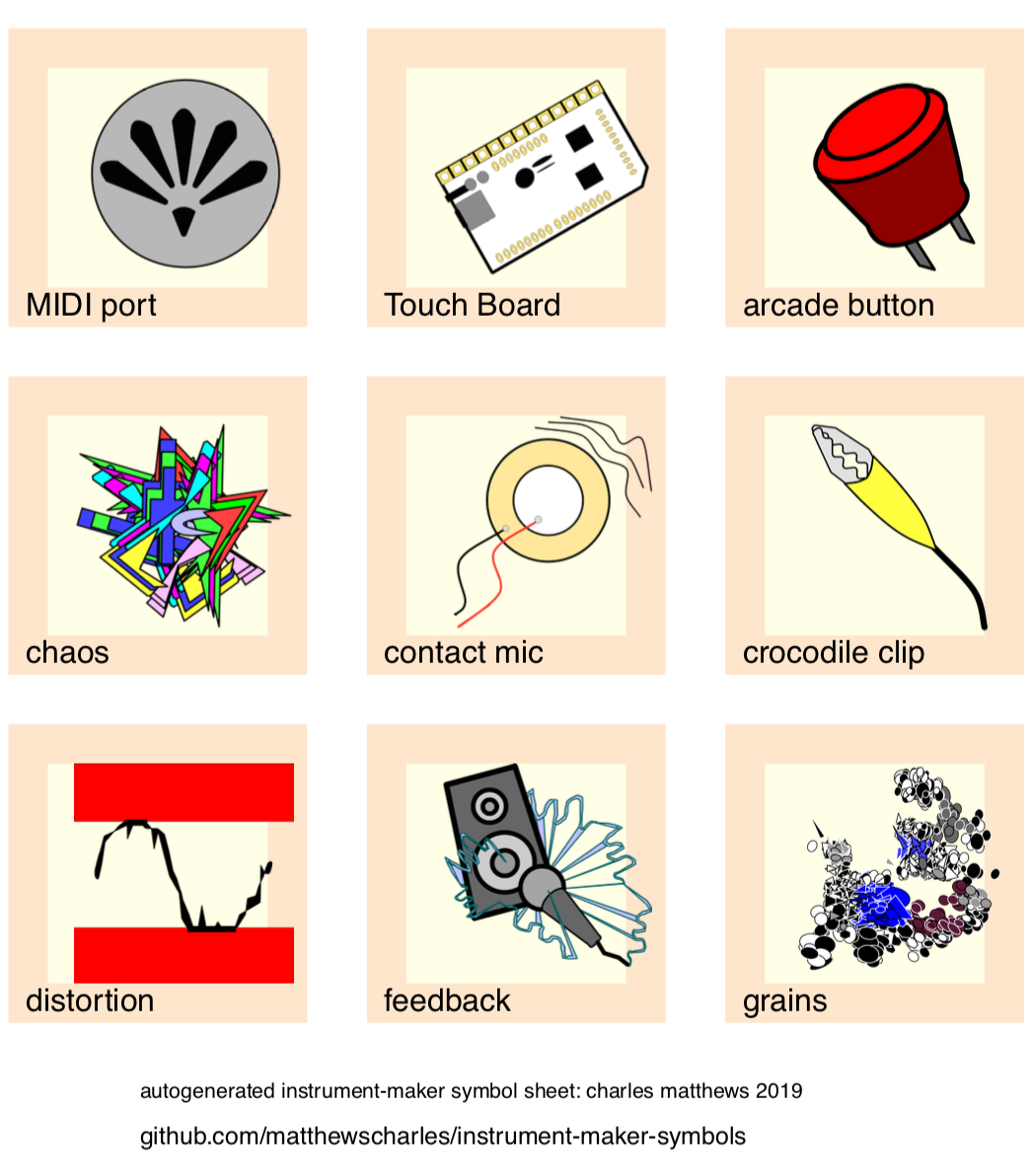

With time, we started to add options for screen reader access, easy read versions of the code, and alternatives to the typical mouse-and-keyboard interfaces upon which this kind of programming environment usually relies. In parallel, the Hidden Sounds sonic arts group at City Lit had started requesting symbols, which we developed together, and eventually turned into a whole collection to complement the code.

Establishing entry points

As a facilitator, I’ve often wondered whether we may as well be learning to code when we’re operating iPad apps and setting presets in a typical school workshop. Before we even make a start, upon the appearance of a computer or circuit board, the feedback I’ve noted from many adults around either format is often quite similar — something along the lines of: “I won’t be able do this, I’m not a technical person”. This is of course a perfectly valid concern, and not everyone wants to become a developer, but I’d like to see how we could challenge this established role, or perhaps any potential divisions around who can and should access the inner workings of these instruments.

A set of colourful symbols used for Instrument Maker.

So the introductory process we’ve worked out for Instrument Maker is very much based on how we’d try to find a comfortable, unpatronising path into these situations, with the goal of making music placed up front: setting out the parameters to make music in an individualised manner, through a series of questions — either in person or through simulated dialog with a computer — which gradually leads into exploring more conventional code if so desired.

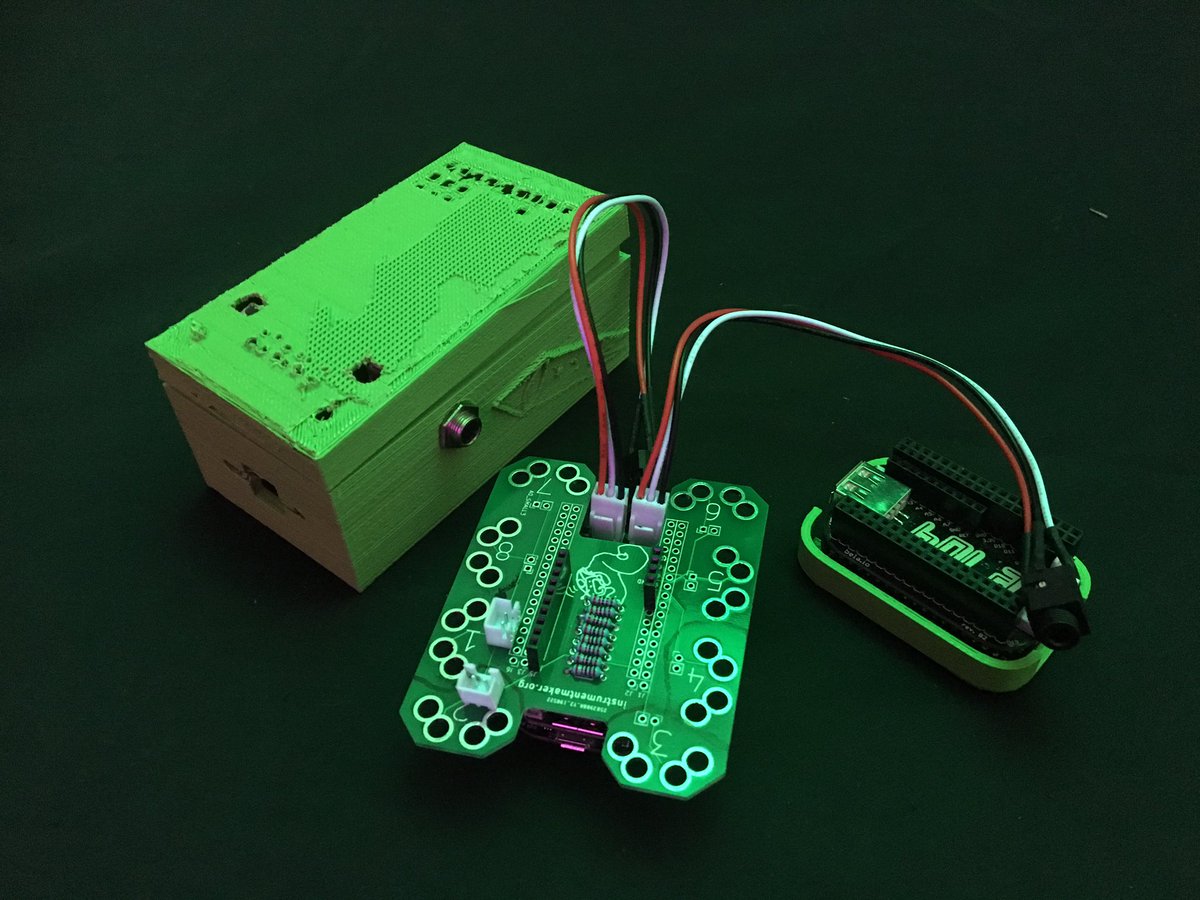

To accompany the code, we use a home-made board that fits on top of the Bela as a sort of shield or “capelet”, with a typical “voltage divider” built in (this is a simple circuit to read the values of a sensor, but not exactly the easiest thing to get to grips with in a first session). Just like the code, this gives us a solid starting point in a workshop or demonstration for some immediate practical outcomes.

Robyn Steward has been instrumental in pushing this forward; we used Instrument Maker to develop her wireless effects pedal (which Robyn has named ‘Barry’), as part of her recent Emergent commission for Drake Music. We recently collaborated on an iPad app development workshop using this code, and the opening statement Robyn wrote on our worksheet is particularly striking: “it’s OK to make mistakes, making mistakes means you’re learning something”. This is an essential qualifier to add to the message so often touted in overtly “accessible” contexts, ie. “this is stuff easy, anyone can do it”.

Robyn's pedal 'Barry Mk3' at a recent performance night curated by QMUL's Centre for Digital Music.

The point is not to attempt to simplify everything, although this can be part of a solution. Simplifying is not good enough if the capacity to adapt and expand is closed off in the process. And this can be downright counterproductive if the results are presumptuous or condescending.

In this kind of endeavour, the real work for a developer lies in creating a way through the objects that help create a learning experience for those that want it, without getting in the way of those people who have the experience and confidence to get stuck in straight away. This isn’t the sort of thing that can be guessed or worked out through “empathy” – it’s only going to come about through conversation and direct involvement. And furthermore, there should be space to approach the technology independently – sometimes the best way of creating access can be through adopting an open source approach.

And of course, not everyone seeks independence or aspires to be an audio programmer. In fact, it can be damaging and frustrating to present a false impression of independence, an implication that everyone could do this unsupported. Rather, we want people to know that the possibilities are out there, and that these shifts in power can take place.

That’s it for now… please let me know what you think of all this (the most immediate way is to tweet me at @matthewscharles).

You can learn more about Charles’ work on his website: ardisson.net and at instrumentmaker.org.