The Book of Knowledge of Impractical Musical Devices

Three thought-provoking instruments made with Bela

In this post Yann Seznec introduces the Book of Knowledge of Impractical Musical Devices. This series of three musical devices are each guided by very specific rules which encourage players to reflect on their listening experience. Here Yann focuses on his auto-destructive work, Volume 3: Everything You Love Will One Day Be Taken From You.

Everything You Love Will One Day Be Taken From You

I had a conversation a few years ago with a friend who works in art conservation. She told me that paintings slowly decay, through the act of looking at them. The light that we need to see a painting is in fact destroying the pigments that we are looking at. Our eyes are killing the artwork. This made quite a big impression on me, and of course I started to think about how I could apply this to the medium that I work in most often - sound. Would it be possible to make a listening system that would slowly, but permanently destroy the sound through the process of listening?

Auto-destructive Art

This idea certainly falls under the category of “auto-destructive art”, and it has a great history - perhaps the most famous sound art example would be Alvin Lucier’s I’m Sitting In a Room. That kind of work influenced the idea significantly, but I wanted to update the concept to take advantage of new digital technologies that allow me to take it even further.

With William Basinski’s Disintegration Loops, for example, you can always start back at the beginning to listen to the non-destroyed sound. What if I made a system where there really wasn’t any way back, where each time you listened it would be irreversibly changed, each playback of the recording losing some of the original signal until it was gone forever?

Book of Knowledge of Impractical Musical Devices

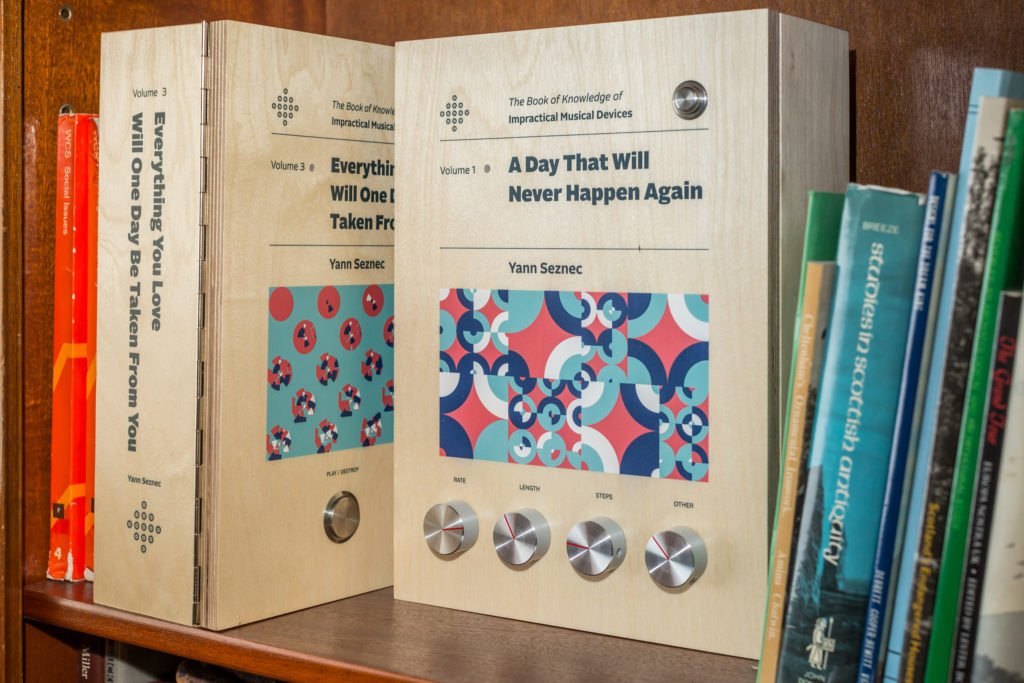

This ended up becoming a part of my Book of Knowledge of Impractical Musical Devices project - an attempt to make a set of musical instruments that took fundamental rules and limitations to their logical conclusions, often raising uncomfortable questions along the way. I made three instruments, which I called “Volumes”

Volumes 1 & 2

The first two volumes of the project are about memory and remembering and listening and forgetting. Volume 1: A Day That Will Never Happen Again takes the form of a rhythm machine that will never play the same patterns from one day to the next: an instrument with a fleeting memory that must be enjoyed in the moment. Volume 2: Here You Are, You Are Here on the other hand takes place as it’s main control parameter: depending on geographical location a granular synthesis engine will reshape and recompose the recordings stored on the instrument.

Volume 3

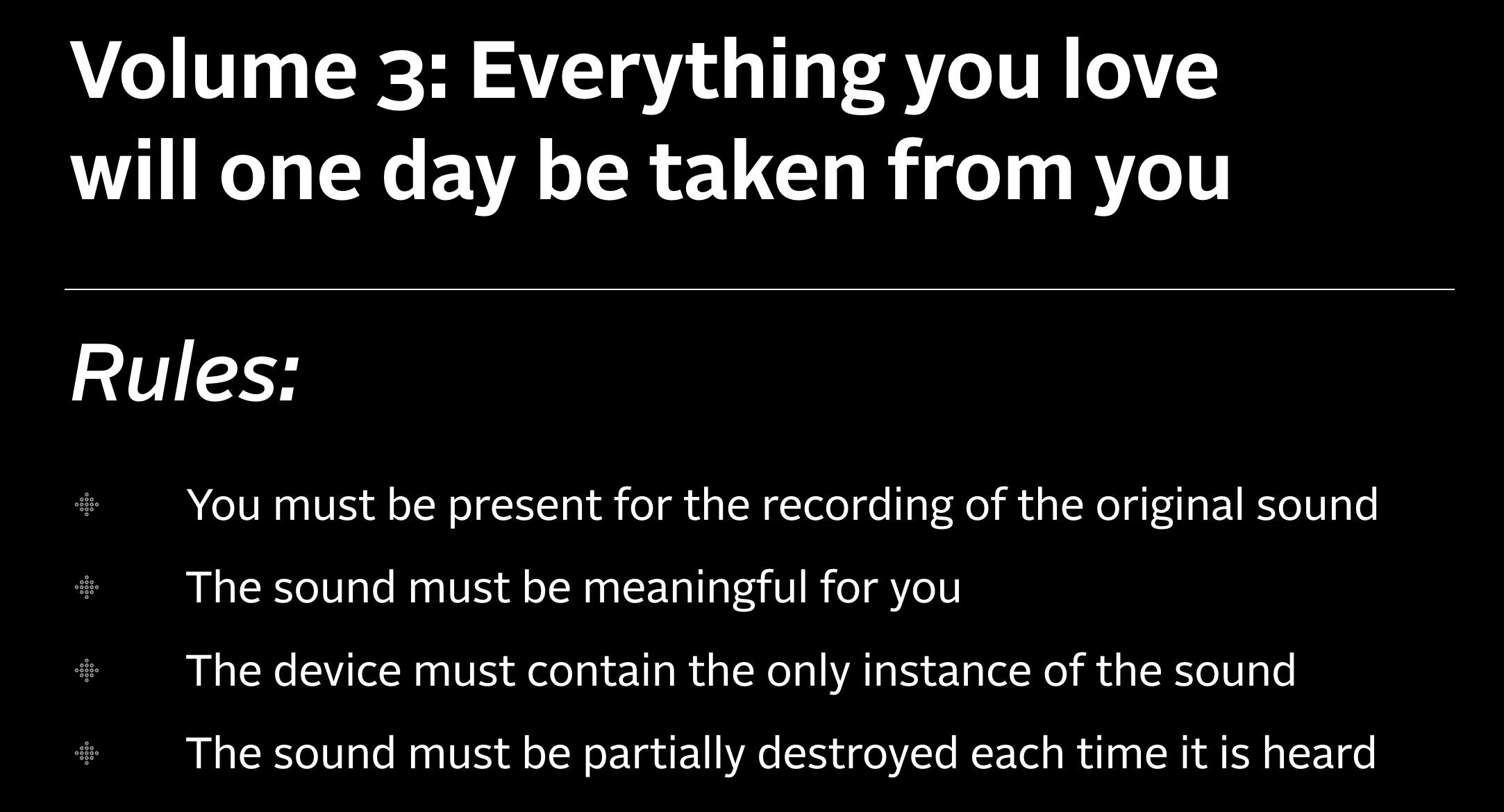

Volume 3: Everything You Love Will One Day Be Taken From You is the focus of this post. Each volume had a set of rules that guided my design - here are the rules for Volume 3:

Of course a lot of issues arise when you start trying to design a system like this. How can I make sure that the sound is completely destroyed? The first step was to consider how to add the sound into the instrument. Loading a sound from an SD card or some other external source is problematic, because it means that the original sound will likely survive somewhere. It’s surprisingly challenging these days to make sure that a file exists only in one place - when I record a sound on my handheld recording machine it will stay on that SD card for ages, and the file itself is probably recoverable even after I delete it. Once I put it on my computer it will be automatically uploaded into the cloud in various ways, and probably copied onto a backup drive - each of these virtually guarantees a life beyond what I can control. I realised that it was absolutely crucial that the file that was being destroyed needed to be the only copy in existence. If there was any possibility that the sound existed elsewhere the destruction would have no emotional power whatsoever.

Construction

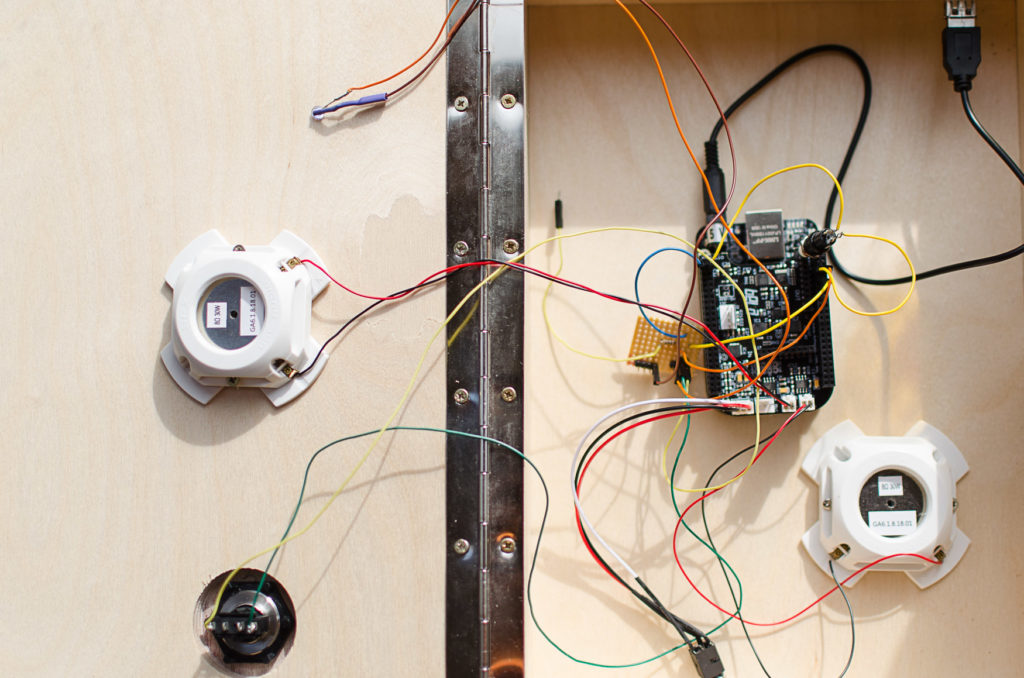

That was probably the point at which I decided to use a Bela for this instrument - the high quality built-in audio inputs provided me the perfect solution to this problem. The instrument could have a microphone input for recording sounds directly into the destruction system, ensuring that no other copy of the sound exists.

Similarly, I realised that if there was a headphone output then the resulting sound that the instrument makes could be recorded at near-perfect fidelity, and this could potentially ruin the integrity of the experience. I also thought it would be best to make the interaction as seamless as possible, and putting headphones on (or plugging into speakers) can really slow things down. So I decided to use the amplifier output from Bela to send sound to vibration speakers, which would be attached to the housing of the instrument itself. The object would become the speaker.

At a certain point, of course, one needs to accept the limitations of the rules that are set for any project - certainly someone could point a microphone at the instrument to record the sound, or plug Bela into a computer and copy the PD patch containing the sound, but these things seemed both insurmountable and unlikely. I did, however, decide never to make any videos of the instrument in action with the final sound.

Destroying Sound Through the Act of Listening

The next important thing was to work out how exactly the sound would be destroyed. I decided to use the software tool I was most familiar with - Pure Data (PD), partially because I am very comfortable using it and also because of the ease with which I could run the software on a Bela without any worries about stability or performance issues. I love the IDE system for loading patches, and how quickly you can get it up and running.

But destroying a sound in a satisfying way is surprisingly tricky! I decided early on that I wanted a button that could be held down to loop the sound, and on every loop the sound would degrade slightly. My first attempt at this was to simply write little bursts of random noise into the sound buffer on each loop, essentially placing a few random values into the sound wave. This was surprisingly (to me) unsatisfying. It ended up just sounding like digital crackle, which in many ways made the original sound even more clear, because my ears would focus on the underlying sound. It was also extremely inefficient and would slow the patch down significantly because the quantity and range of numbers to write sequentially to the buffer was pretty enormous. Back to the drawing board.

After some experiments I decided that perhaps it would be most effective to cut it up, rearrange it, mix it around so that the glitches and destruction would be on some level recognisable as part of the original sound. In some ways I was thinking of this like a photograph being destroyed by being sliced apart and put back together, always keeping the original shape but fundamentally changing the image until it was just noise.

The method I settled on to achieve this was a type of wavetable playback. So I set up a wavetable to play the sound - this wavetable starts straight, so the first time the sound is played it is unchanged. However on each playback a “glitch” is written into wavetable. This glitch is a line but can have any slope, a range of lengths, can go either direction, and can start at any point along both the X and Y axes. This will of course change the playback of the sound, but it will still be the sound itself playing back, just in a somewhat broken way.

The output from this playback is sent to the speaker, of course, but it is also sent into the buffer at a slight delay, to overwrite the original sound. One of the unintentional consequences of using this method is that the wavetable playback is slightly offset on each loop, which means that the glitches can continue to change the sound and also the sound slowly fades away - I’m still not completely sure why that happens but it is an amazingly effective thing to hear. This works super well even with a stock sample like a snare drum…something about the repetition and rapid degradation pushes it into something like “I’m Sitting In A Room” on steroids.

Book binding

With the software more or less finished I concentrated on the interface. I made a few different cardboard prototypes, and eventually housed it into a cigar box. I made a video showing it in action, which attracted a great deal of lovely attention on Instagram, and some hilarious feedback on YouTube.

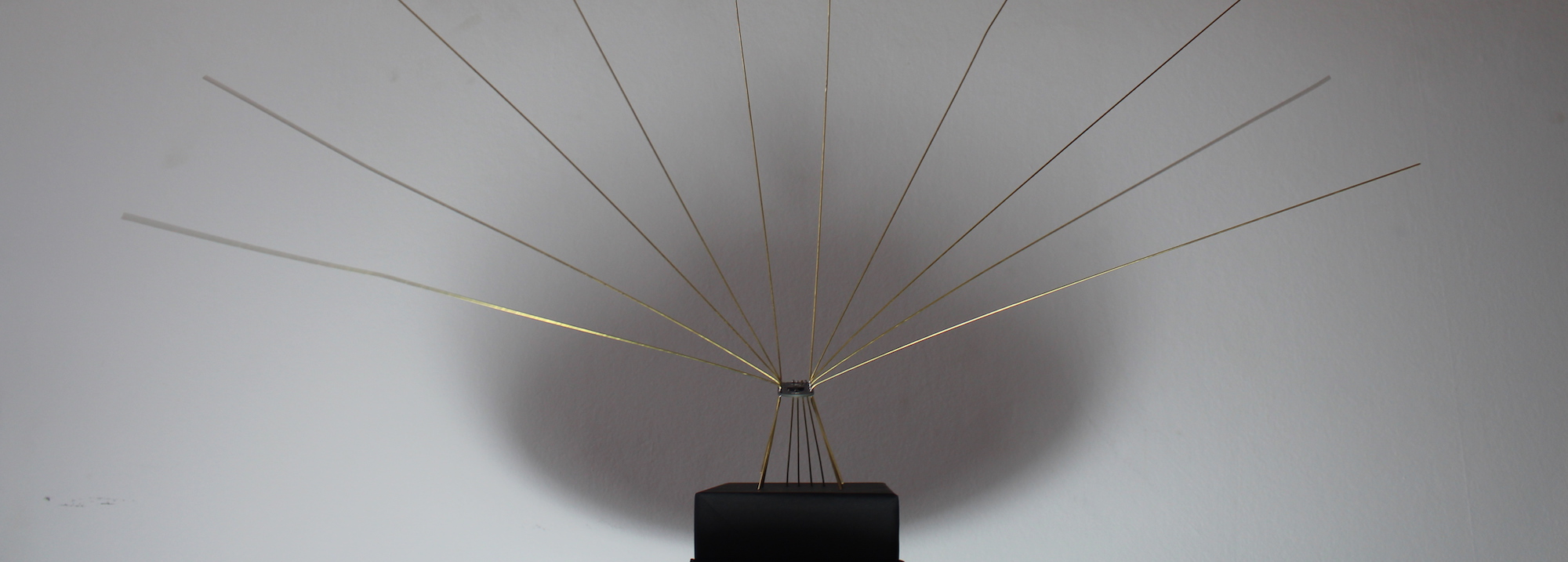

The final stage was to integrate it into the Book of Knowledge of Impractical Musical Devices project, with a wonderful design by Tommy Perman printed on handmade wooden boxes. The final design used a single large metal button labeled “Play/Destroy”. The button for recording a new sound is hidden away inside, along with the microphone - this is deliberately hard to access, because I wanted the act of recording a new sound to be very rare.

The project as a whole is deeply focused on documentation and sharing, so the project website has all of the code and plans for making it yourself (as well as an essay outlining the conceptual reasons for it). This website is perhaps the most crucial aspect of the project, and it’s the part that brings it most closely in line to one of the biggest influences on the work in general - the 12th century Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices by Al-Jazari. I realised very early on that the project should not only be open source technically, but also conceptually. Most of what I accomplished in the project has been technically achieved by people across the internet, and could be cobbled together in the same way that I did by googling and checking different forums. However the thought process is not something that people tend to elucidate.

However of the three instruments I made this was also the hardest one to document, because I didn’t want to make a video that showed the sound that the instrument contained. I ended up finishing everything to the point where it worked but did not have a sound, and then making a video where I show myself recording a sound that isn’t important to me (see the rules above!). So I had to bend one rule in order to show people the project on the internet.

Once I was finished with the video I took the instrument home in order to completely finish the project by recording a sound that was somehow important to me. I had it in my living room and I was playing with my son the next morning, which was a part of our daily routine that I thought would be nice to capture. I brought out the microphone and just as I pressed the hidden button to record him he became interested in the object and said he wanted to press the button (which called a “beep”). It immediately started playing back his own little toddler voice saying “press the beep”, and the longer he held it down the more it was already being destroyed. That moment was already being lost. I thought I was emotionally prepared for this, but I can assure you I very much was not. That was the moment where I knew the project was complete, and I think it’s the moment where it felt like it had succeeded.

About Yann Seznec

Yann Seznec is an artist and musician whose work focuses on sound, music, physical interaction, games, and building new instruments. Recent projects include residencies at the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum, the Floating Cinema in London, Playable City Lagos, and Timespan in the Scottish Highlands. He has performed at The Roundhouse London, Mutek Montreal, Melbourne Recital Hall, Liquid Rooms Tokyo, Köln Philharmonie, Fak’ugesi Johannesburg, and more. Much of his work involves building custom instruments such as musical pigsties, slinky instruments, candle-based sound installations, electromechanical mushroom spore reactors, and more. You can find out more about his work on his website.

A huge thanks goes to Yann for sharing this project with us.