Hacking the Five-String Banjo

Re-imagining the banjo with Bela and Supercollider

In this post Jonathan Reus introduces us to his augmented Appalachian banjo which was created during a residency with us in the Augmented Instruments Lab. The instrument brings together prototype Trill sensors, magnetic sensing and Bela.

Hacking the Five-String Banjo

In the summer of 2019 I was graciously received by Andrew McPherson and the rest of the Augmented Instruments Lab at C4DM in London for a series of micro-residencies. I’ve had a longstanding interest in “old time” American folk music since getting wrapped up in that culture a lifetime ago when I lived and worked in Northern Florida. You may have heard that Florida is the state where the farther north you go, the farther South you get.

A lot of that hands-on, material/social-oriented cultural ethos that I associate with Southern craft and folk art still sticks with me in the way that I approach digital music, in that I often see new technological approaches to art-making from a perspective grounded in materiality, sociability and egalitarianism. In some senses, folk instruments and music practices could be thought of as an archetype of the “convivial technology” that philosopher of science Ivan Illich described in his 1973 book “Tools for Conviviality”.

“Whenever different cultures meet, new instruments happen”

American folk instruments and music have transformed historically through convoluted evolutionary paths; passing via different geographic enclaves and waypoints, heterogeneous mixtures of cultural attitudes towards music and playing. The 5-string banjo is an interesting example of this. It’s an instrument that’s the result of a confluence of cultures and is representative of a complex history with extremes of deep inequalities based on race and class at one end, and the ambitions of elites and industrialists at the other. It’s one of the few musical instruments that I can really stamp as representative of American history and culture. Next to the banjo, what else? Maybe the electric guitar? The turntable?

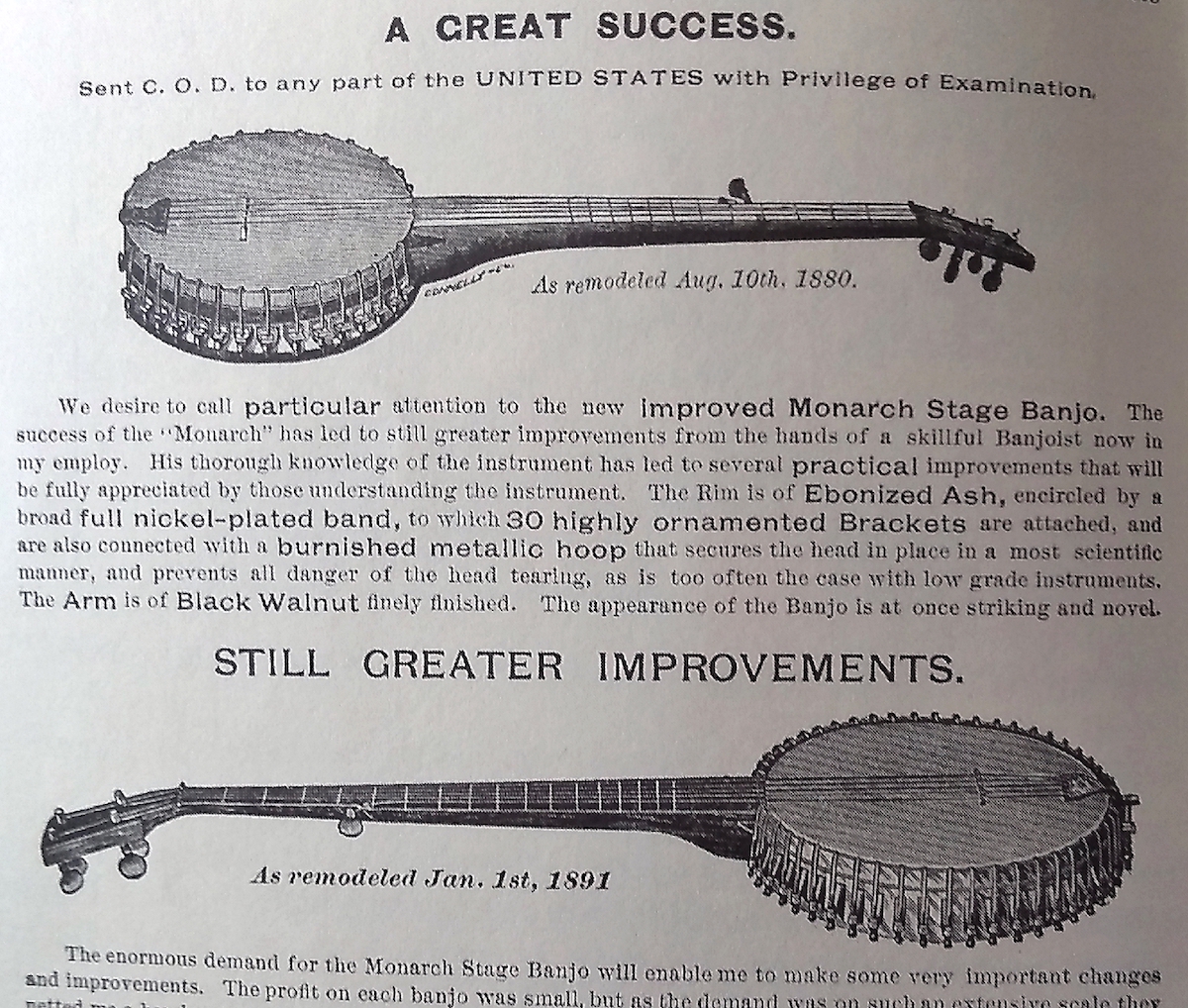

Despite its rustic aura, the 5-string banjo’s history holds within it modernist mythology. During a period in the 19th century there were certain (white) entrepreneurs who, through varied combinations of musical idealism and business opportunism, wanted to … for lack of a better term … “rescue” the banjo from its reputation as a crude and untamed instrument (a reputation strongly linked to its association with African music). The 19th century elite believed that civility came through the development of high levels of technology. The industrial revolution was in full swing, but the banjo’s story puts into relief the fact that this was not everybody’s revolution.

This is the time when the 5-string started morphing from all-wooden or gourd-based designs to the metal tone rings and steampunk-esque tension brackets that you see today. The push to industrialize and mass-produce the instrument also came at a time when the first truly American pop entertainment form, the blackface minstrel show, was coming to prominence and popularizing the banjo as an object of popular culture. Take one cup historical revisionism, mixed vigorously with romantic nostalgia, add two tablespoons of technological fetishism and garnish with a dollop of industrial capitalism.

Kalebas banjo from 1770 Surinam, the oldest surviving banjo from the American continent, Tropenmuseum Amsterdam: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.11840/609575. Five-string fretless banjo from the National Museum of American History.

While most modern banjos still sport a reduced version of the industrial makeover the instrument received in the late 19th century, there are specialty luthiers out there making pre-industrial banjos, harkening back to the kinds of instruments that would have been played in the Caribbean, on plantations, or by poor rural whites who worked side-by-side with slaves. These “mountain” banjos, a kind of a catch-all for any kind of banjo-like instrument made from wood, gourd or kalebas (squash), usually featuring more idiosyncratic designs - smaller and varied pot sizes, fretless and fretted, often home-made, with an ever-present fifth string.

Belanjo or Banjela?

I had started sketching out plans for a prototype hybrid/programmable mountain banjo a few months before coming to London. I was mainly interested in exploring how to build digital extended techniques that could expand on “stroke” styles. “Stroke” styles are a stringed instrument playing technique where the player strokes down with the back of their fingernails on to a melody string and then pulls up with the thumb on another string (usually tuned as a drone). English speakers colloquially refer to this kind of playing as “frailing” or “clawhammer”, but the origins of this playing approach, much like the origins of the banjo itself, are rooted in African musical techniques on spiked-lute instruments like the Akonting (see Daniel Jatta) or the Gimbri used in Gnawa music.

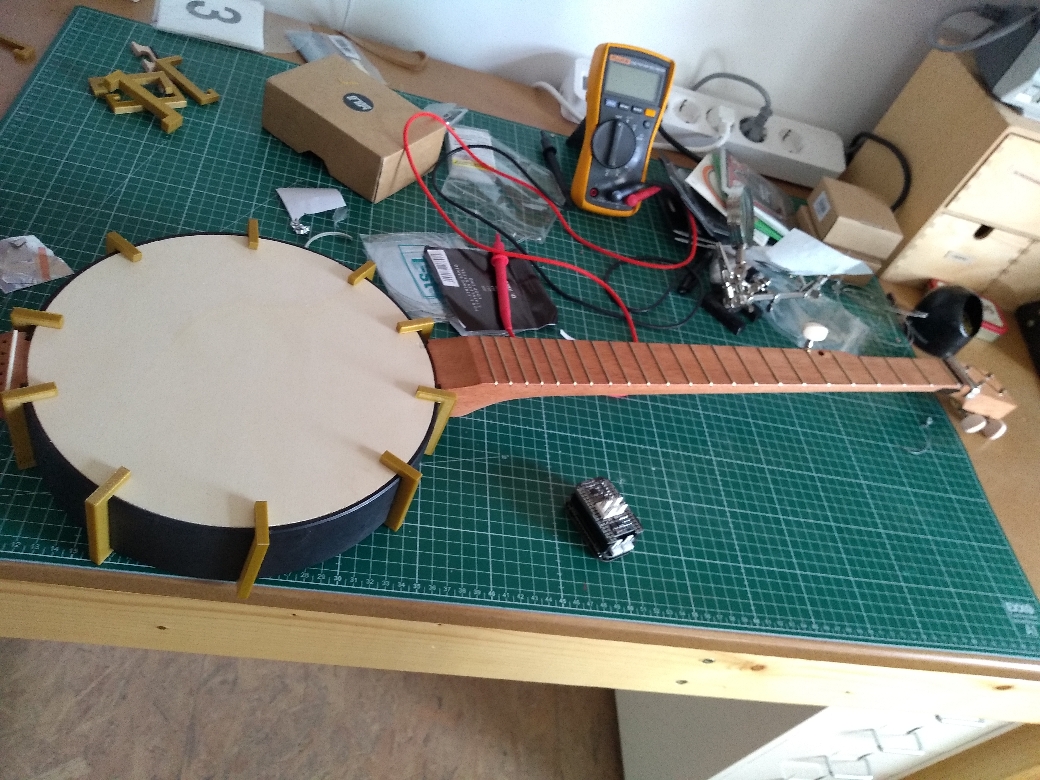

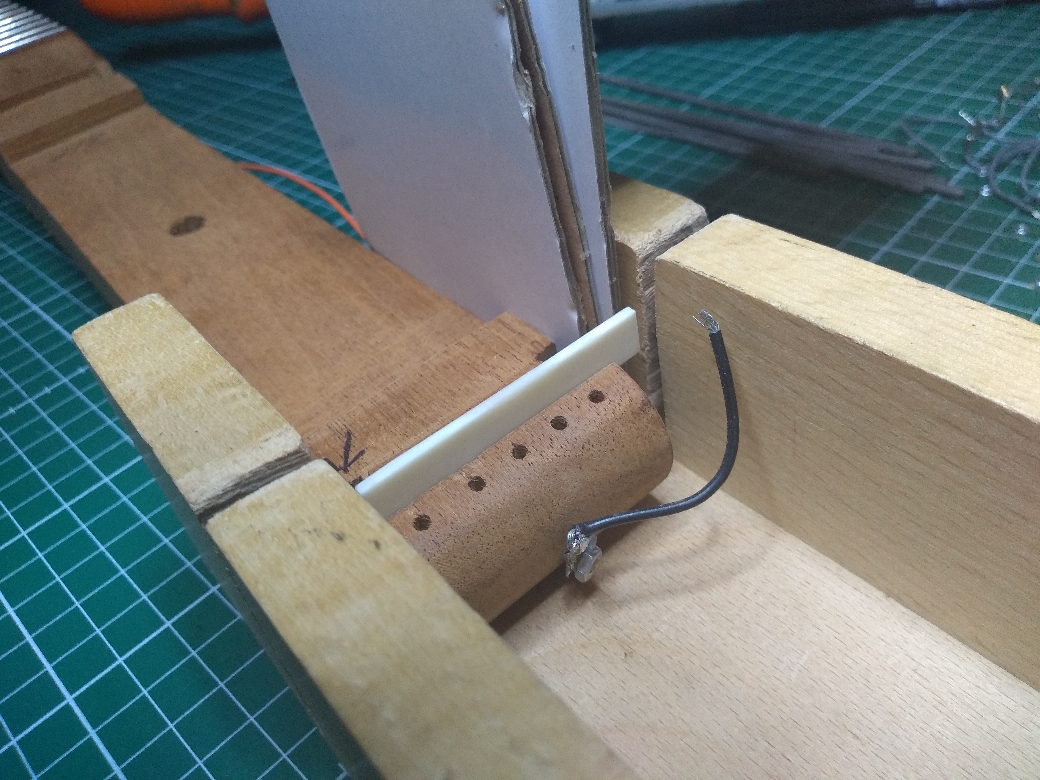

Partly assembled banjo with wooden head and 3D-printed brackets used for holding the whole neck+pot+head assembly together without glue.

To get started I found a lovely DIY banjo kit from the luthier shop Backyard Music. I chose this kit because, unlike most banjos, it doesn’t have a drum skin head, but rather a very thin piece of wood that can easily be modified or swapped out for other head materials. It also sounds surprisingly good, has a full-size neck, and can handle steel strings without a problem (important for the pickup design > see “Going Electric” below).

Right Hand Technique

Dana Immanuel and I in the studio at C4DM.

When I used to work at STEIM in Amsterdam, we would often have long and rich conversations around the studios about the needs of musicians in electronic music instrument design. At the time we considered ourselves explorers of new musical forms first, and engineers/designers second. From that music-first perspective, we often would say that you’ve got to find the “core” of your instrumental practice and that all technology would thereafter grow. For stroke-style banjo, the “core” is without question in the right hand.

Stroke techniques are sometimes called “knocking”, because of the way you knock on the head of the banjo like knocking on a door. It’s a more or less constant motion and you don’t want to ‘break rhythm’. While in London I teamed up with banjo diva Dana Immanuel, of Dana Immanuel and the Stolen Band, to experiment with possibilities for extended right hand techniques.

Skilled banjoists like Dana work the right hand at different positions up and down the pot and the neck while playing to vary the timbre and move emphasis from rhythm to melody. There is an especially important sweet spot for frailing near the 19th fret of most banjos (sometimes accompanied by a scoop carved into the neck). This is the location of some of the banjo’s noisiest natural harmonics, and is used for extra oomph when “clucking”, a technique where the down stroke of the right hand plays a sort of muted harmonic slap across the strings to vary up the rhythmic emphasis.

More generally, the closer the right hand is to the bridge, the more upper harmonics are created, generating a brighter, twanging timbre.

Trill and Magsense

From working with Dana it became clear that an old-time knocking banjo player potentially has some free bandwidth in their right hand that could be built upon. To do this I leveraged two technologies that were being prototyped at the Augmented Instruments Lab, the touch-sensing Trill and the magnetic-field sensing tech used to sense guitar picking motions in the Magpick.

Dana testing potential locations for magsense hot spots and Trill inlays.

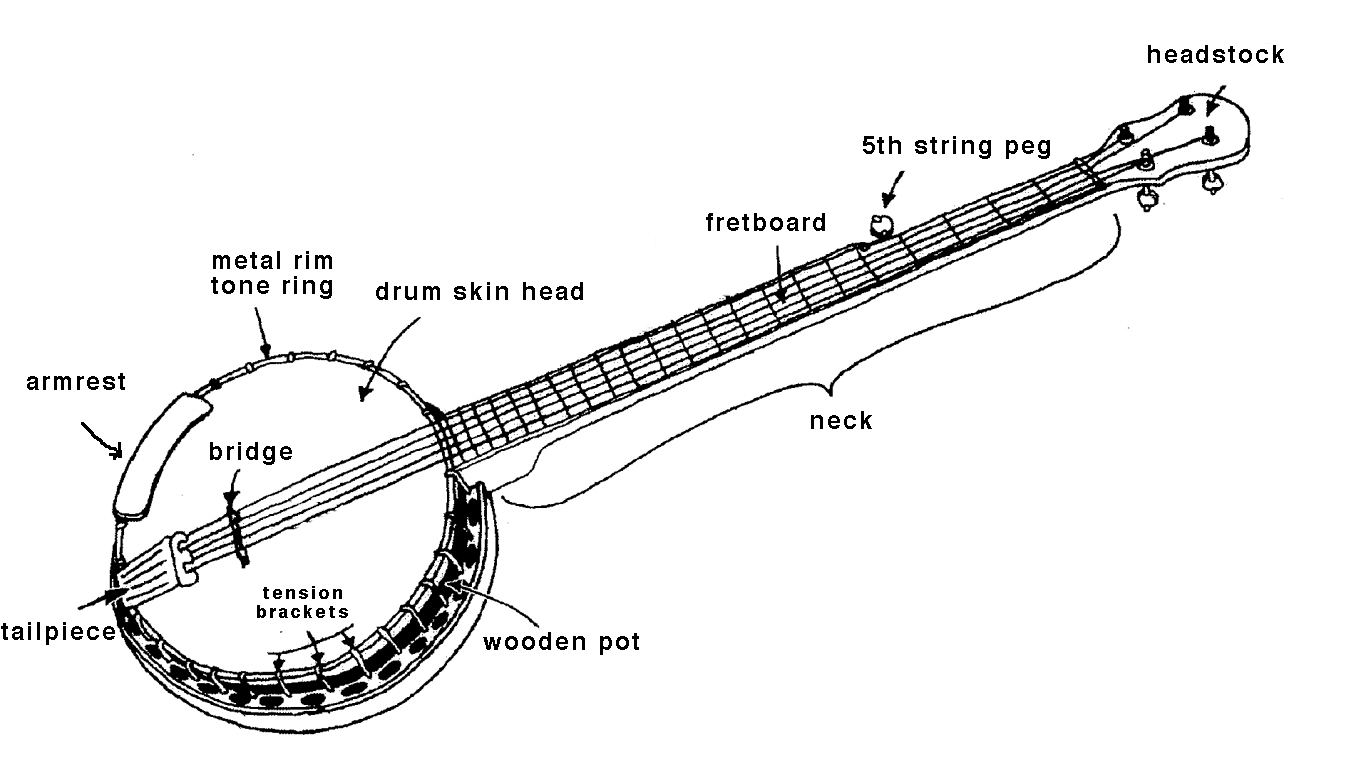

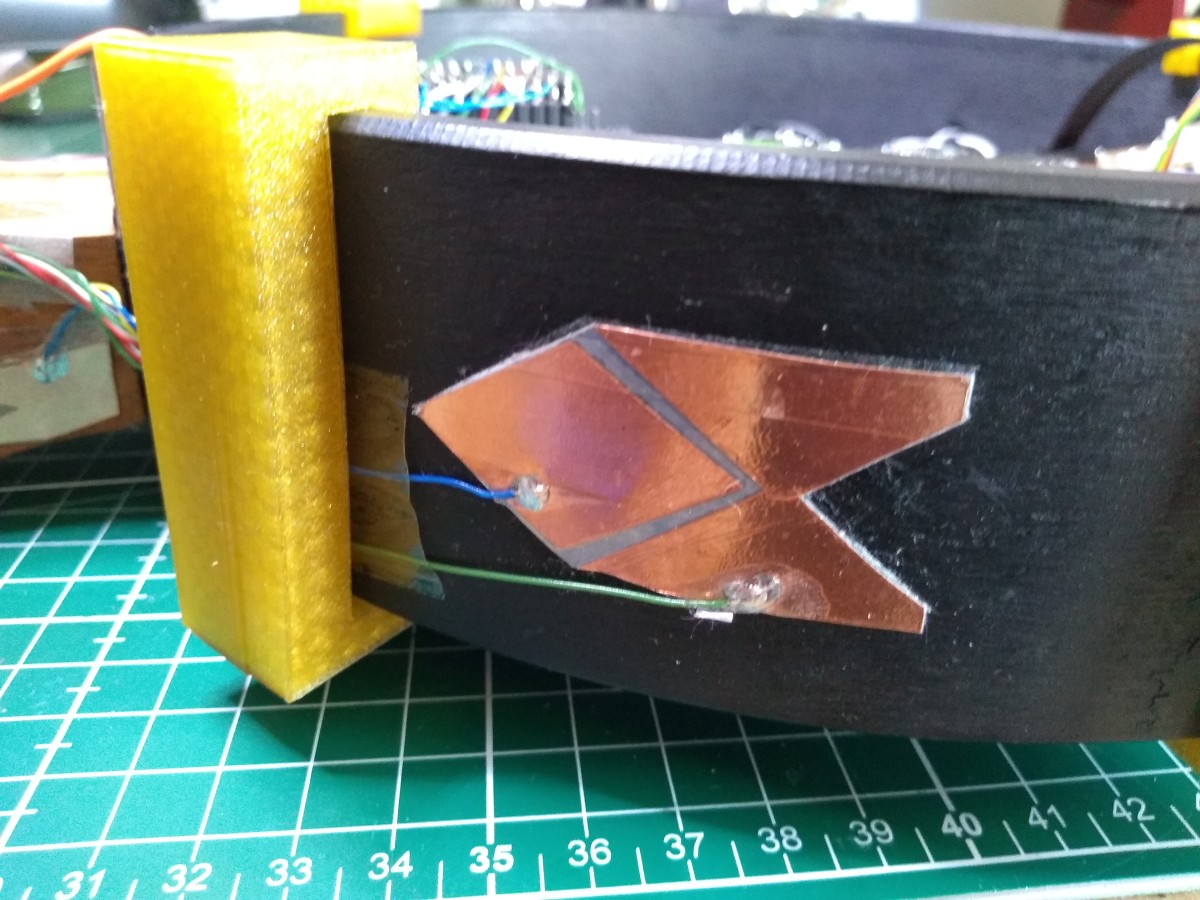

The magpick sensors were integrated into the head of the banjo to track frailing motions and knocking, while custom-made trill touch inlays were positioned at different places along the pot and lower part of the neck to function like extra strings that could be thumbed or scratched without breaking rhythm.

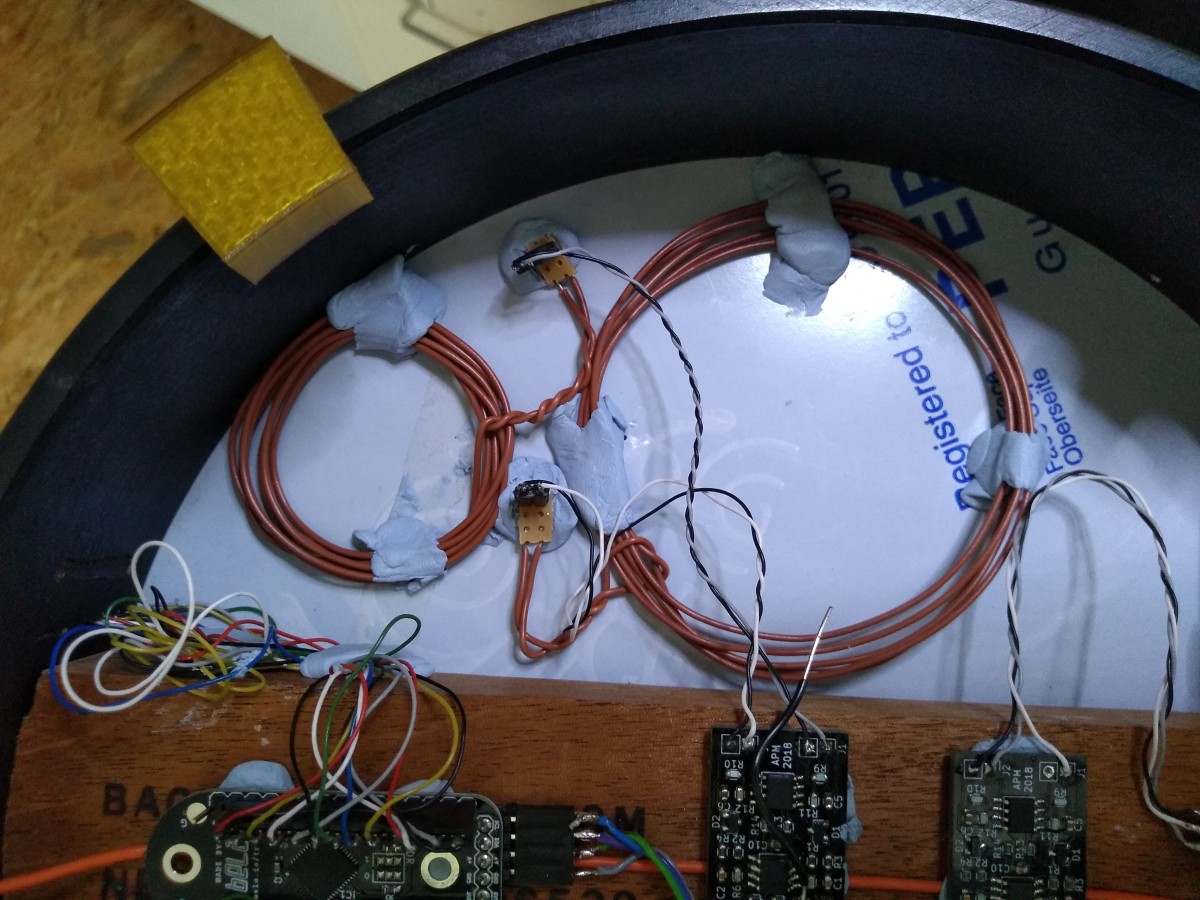

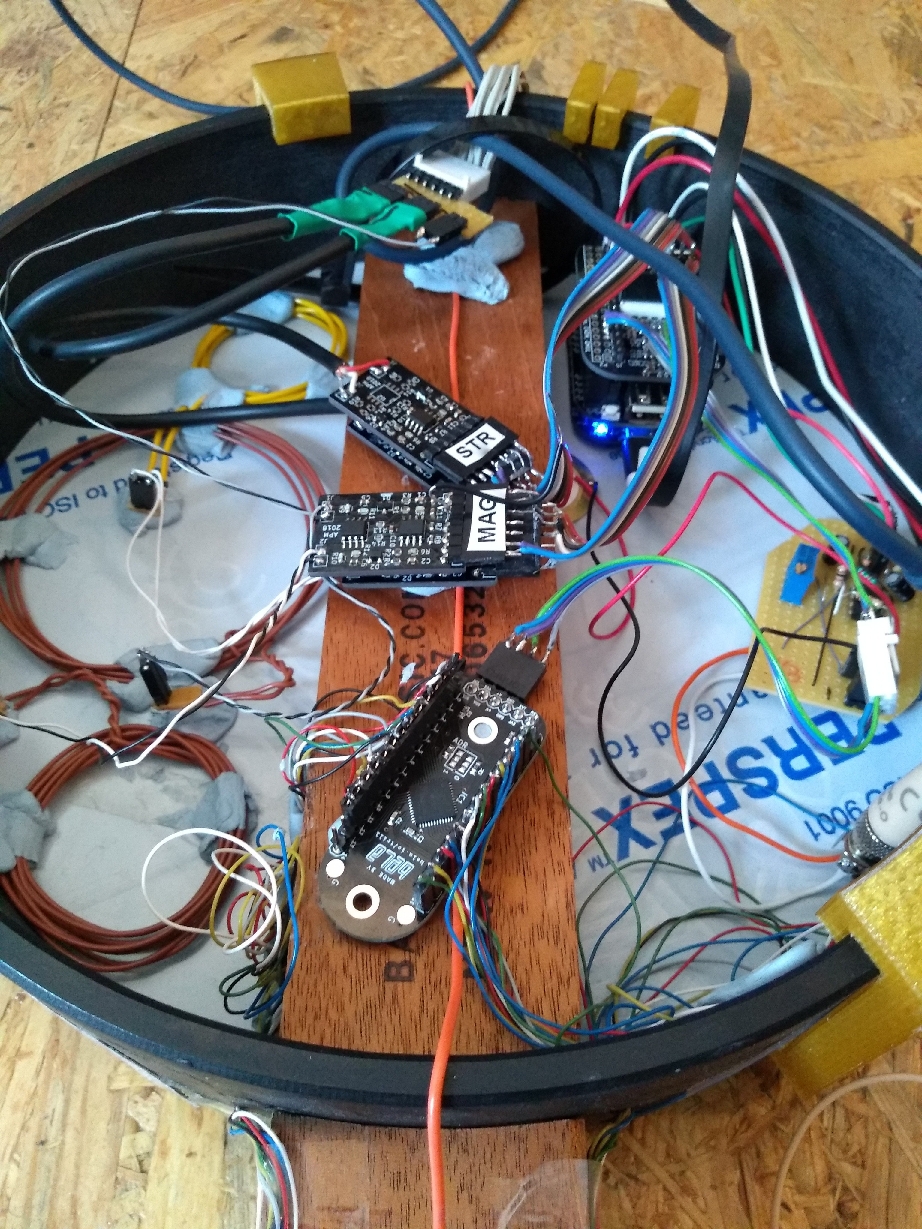

Inside of the pot of a later version of the protoype, with sensor coils on the back of the head.

Since I’m using SuperCollider for all my live electronic sound needs, I needed to develop some custom UGens for the Bela to be able to get the Trill sensor’s data into my signal chains. These UGens are available via my github page for anyone else looking to use Trill sensors with SuperCollider.

Sketching Trill Inlays

From the first time the Bela team introduced me to Trill I started thinking about making touch-responsive copper inlays for the banjo. I’m a big fan of the inlay work done on 19th century American folk instruments and furniture, and the kinds of ornamentation that was popular during the American Fancy movement. I had an Architect friend who told me once that modernist aesthetics have caused us to collectively forget how to be ornamental. I tend to agree. Take a moment to imagine a future for ornamentation.

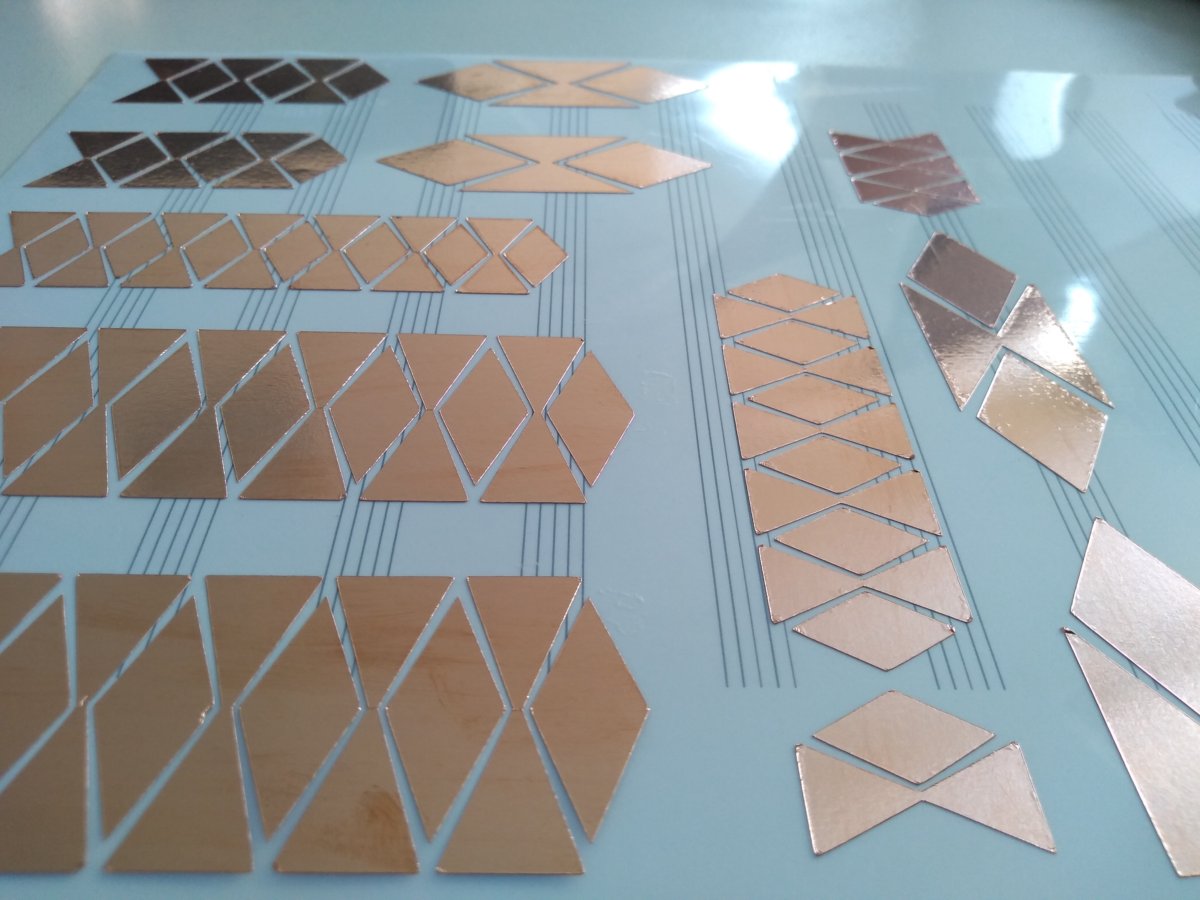

After designing some paper prototypes, taped to the banjo and testing the ergonomics of these along with Dana, I moved on to making some copper stick-on inlays using a vinyl cutter and copper foil. I also used the C4DM’s laser cutter to fashion a new head for the banjo from blue acrylic, featuring some ornamental patterns inspired by the Fancy aesthetic.

Acrylic drum-head fresh off the laser cutter at the C4DM's materials lab.

To attach the inlays I first transferred the cut foil to a piece of thin acetate using transfer tape. Once on the acetate each inlay segment was (carefully!) soldered to a thin-gauge piece of hookup wire. Finally, the whole thing gets ‘sealed’ to the acetate using a piece of transparent packing tape. The packing tape layer has the double benefit of both holding the assembly together and providing an extra thin layer of isolation on the copper, which makes the sensor response more linear when you attach it to a Trill craft board.

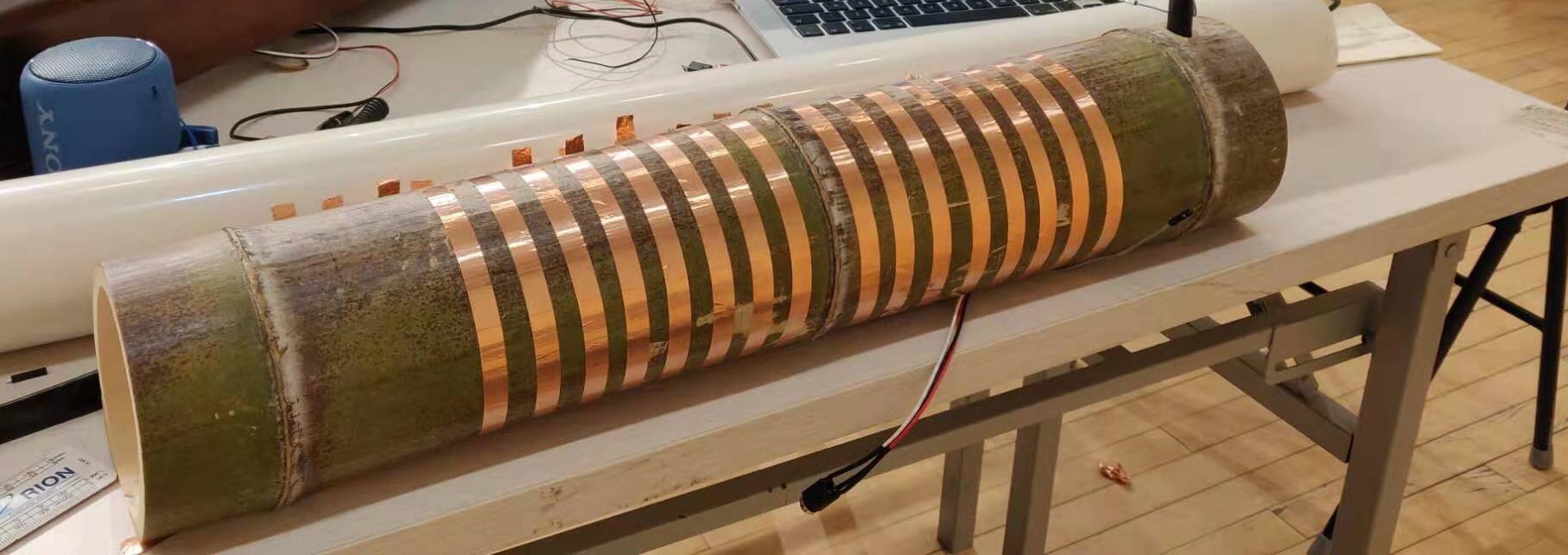

First copper inlays made on the vinyl cutter and then mounted on the banjo neck and rim.

After cutting out the sensor sandwiches from the acetate sheet they’re then attached to the banjo using some double sided tape. This works for now as a proof of concept and playability. For the future I’m still torn between either designing these as flex sensors and running a ribbon connector down the neck, or milling them out of copper plate and mounting the wires behind each segment. In either case, I’d like to give my router and chisel skills a brush up and set them into the neck.

Going Electric

Now how about amplifying those strings? One thing I really love about stroke-style playing is the expressive dynamic variation most players put into it. Give a listen to this recording of Sourwood Mountain performed by Boone Reid. The dynamics ebb and swell, even on a per-string basis. Contrast this against the much more widely known 3-finger “Scruggs-style” techniques used in bluegrass and a lot of modern jazz-inspired banjo playing. These more modern banjo techniques are played using metal finger picks and produce a punchier, more consistent dynamic level (as well as offering higher speed and precision). Personally, I find that the Scruggs-like styles have dynamics kind of like a freight train; while stroke style is like a rain storm, diffuse and temperamental. The latter better fits my personality.

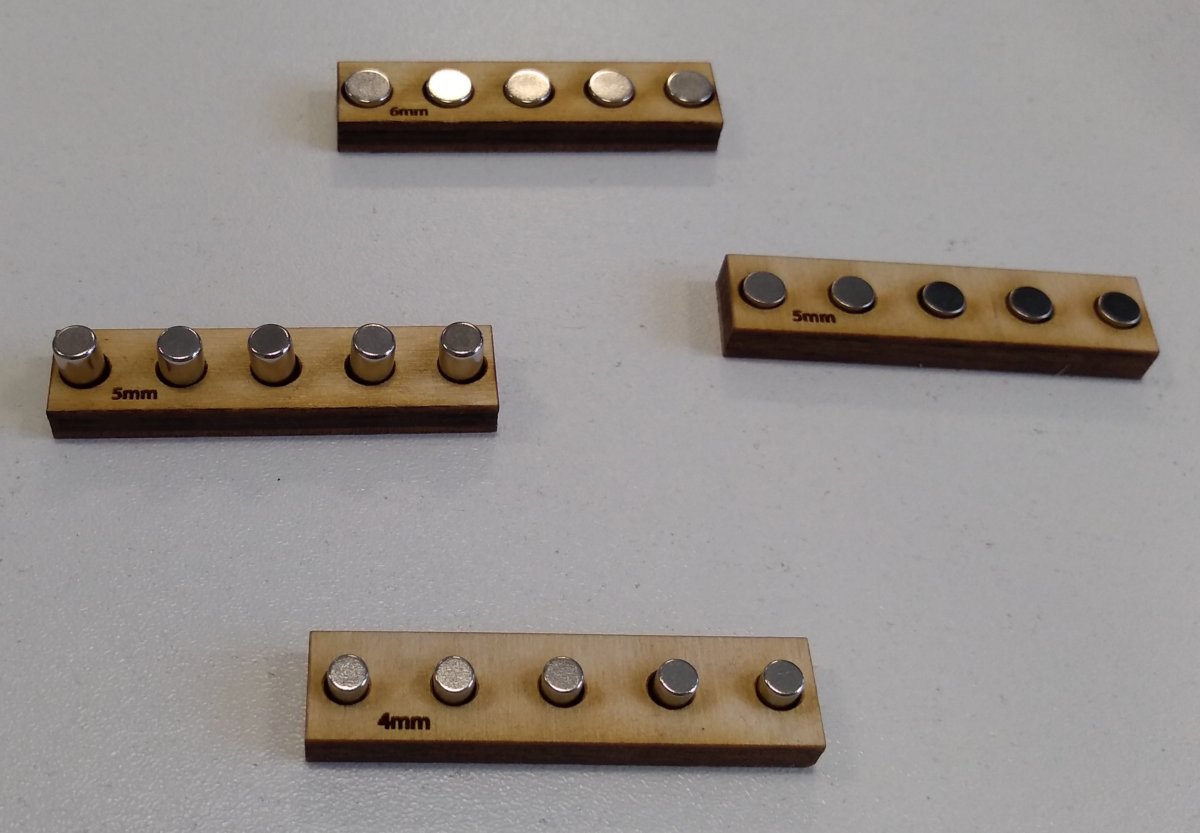

Lasercut frames to experiment with non-destructive mounting of different magnet sizes.

At the C4DM Andrew introduced me to the work of electronic luthier par excellence Laurel Pardue. She had recently finished work on the prototype of a new hybrid digital/acoustic violin called the svampolin. For her svampolin she uses a quirky electric pickup system based on Michael Edinger’s StringAmp which brings with it a couple exciting features like string signal separation and a minimal, non-invasive design (just stick a few magnets near the strings). Signals are picked up at the tail end of the instrument from the strings and created by placing fixed magnets in close proximity to where each string vibrates. It’s a bit like an inversion of the classic electric guitar pickup design.

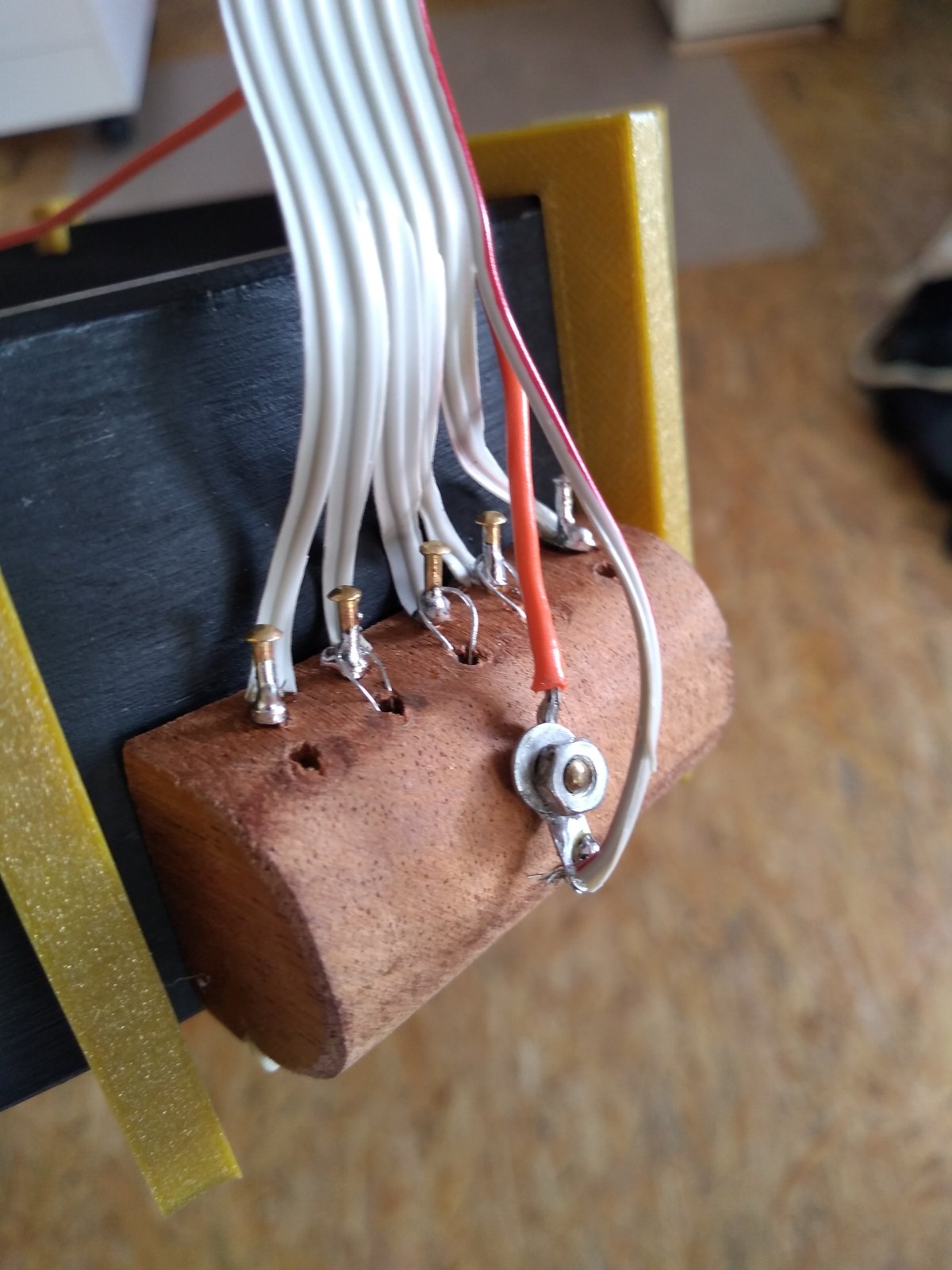

Installing a bone tail to replace the conductive fret built into the kit.

Getting the pickup system to work was a lot of trial and error, and required learning a bit of basic lutherie to remove some frets and fashion a non-conductive bone tail (most banjo tail pieces are made from metal). For the moment the fixed magnets are embedded into a wooden frame and stuck to the head with blue tack so they can be adjusted to different locations. In the future I’m looking to get them out of the way of the right hand by embedding them into the neck.

Left: modified hoop-string tail system for picking up signals from the strings. Right: inlay prototypes mounted on the banjo neck and rim.

What’s Inside

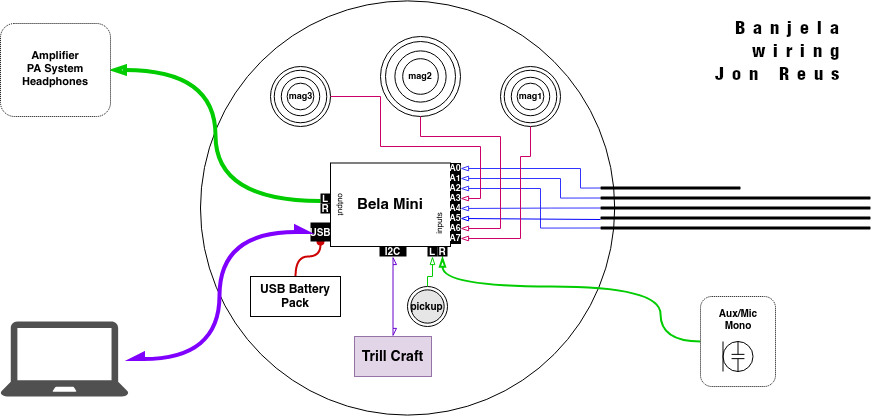

Inside the banjela is a Bela mini with its analog inputs used to full capacity: there are five independent signals (one for each string pickup) going into 5 analog inputs, three magpick sensors going into the remaining 3 analog inputs, and the copper inlay sensors wired to a Trill craft, connected to the Bela mini via I2C.

Banjela backside, here shown plugged into a laptop via USB for reprogramming.

The whole thing is a stand-alone hybrid electronic instrument, powered by an off-the-shelf USB power bank. There’s a single stereo 3.5mm headphone jack output that combines the banjo’s acoustic signal with reprogrammable DSP and synthesis, written using the SuperCollider music programming language. The banjo can be reprogrammed live, or live coded, if you hook it up to a laptop via USB.

Acoustic Signals: Voice and Pickups

The Bela mini’s highest quality audio comes in through the main stereo inputs, which go to a specialty audio codec chip instead of the lower quality ADCs used by the 8 general purpose analog inputs. I reserved these two channels for capturing the acoustic sound of the banjo.

One stereo input is dedicated to a piezo pickup attached to the banjo’s head right behind the bridge. This allows for creating a mix between the acoustic sound and electric pickups in software. The second channel of the stereo input is left open to plug in whatever you like - opening up the possibility of feeding instrument signals from other musicians into the banjo for analysis and processing.

I was most interested in using this second input for live sampling and processing of voice. American folk music tradition nearly always involves vocalizing in as many ways as there are individuals. Hollars and work songs are remixed into gospel and blues. What European music calls “untrained” is more a deafness to the connection between music and lived experience.

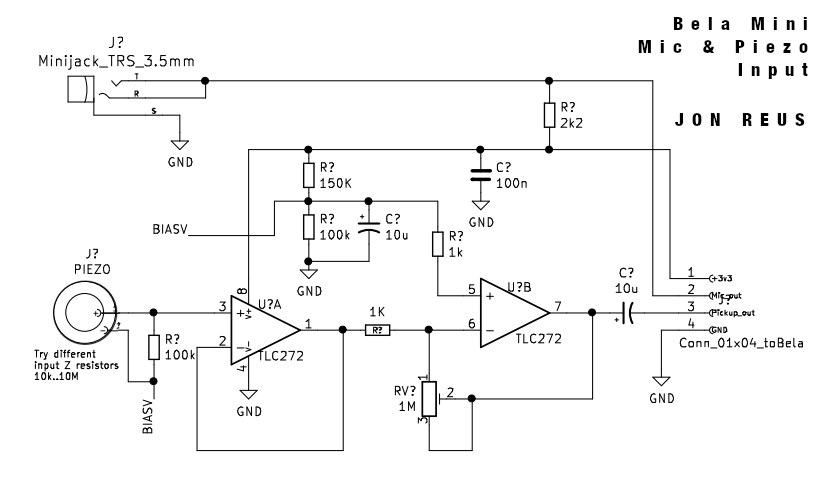

Stereo input pre-amp and mic power circuit.

I built a combined pre-amp circuit (powered by the Bela mini) that provides a high-Z interface for the piezo pickup and also a powered input for electret microphones. For voice work while playing, there are a number of affordable head-mounted condenser microphones, or you can build your own. I’ve been using the t.bone Headmike, which is a discount model designed to be compatible with Sennheiser “EW” wireless mic systems. Most of these microphones need a bit of power to work ~ the Bela Mini’s 3.3V supply is just enough, fed through a 2.2kΩ resistor.

Embedded Processing: A Bird’s Eye View

That’s a lot of signals going in and out of that little Bela mini. Wouldn’t it be nice to see what’s coming in from the banjo somehow?

The Bela team had just released a new browser-based GUI system when I was doing my residency, and naturally they were happy to recruit me as an alpha tester. I wanted to have a dashboard for the purpose of debugging signals and making sure everything in the banjo was working hardware-wise. So, starting with some of the examples provided in the Bela IDE, I started building up a signal visualization system. At the time there were some things I needed to visualize that weren’t available in the examples: such as needing to view audio waveforms coming in from the strings, and being able to split up a single Trill craft sensor into multiple segments.

For these use-cases I built out two new GUI widgets and then started arranging them visually so that they more-or-less matched their arrangement on the banjela.

All in all I had the following that needed to be represented:

- one microphone signal

- one piezo pickup acoustic signal

- five audio signals, one for each of the five strings

- three magpick sensors on the head

- one trill craft broken into five segments (two long segments on the bottom of the neck, one on the top by the thumb, and two small segments on the pot)

Stereo input pre-amp and mic power circuit.

Anyone out there is welcome to use my GUI widgets in their own Bela projects. You can find them on github here.

Sound Design and Songwriting

For a first attempt at songwriting for this instrument I made a suite of three songs, each exploring different extended techniques.

Mapping and sound synthesis in this case was a pretty elaborate process, and is way too much to go into here. But below is a small example of SuperCollider code that shows off a couple of my sound design tactics.

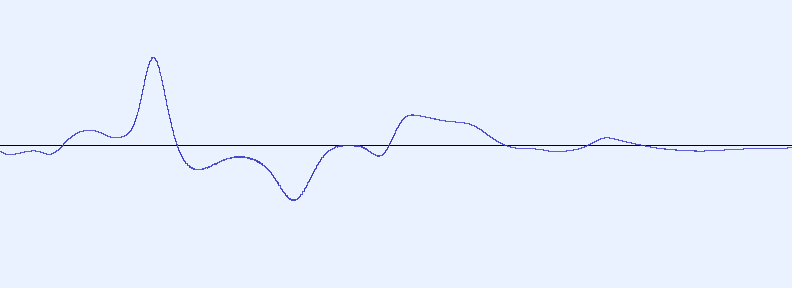

Here I’m mapping the Trill segments above and below the neck to synthetic strings. And using the magpick sensors on the head of the banjo to control forward/backwards sample playback of percussion instruments.

Waveform of a single right-hand stroke captured by the magpick sensor. This signal gets mapped to forward and backward sample playback.

~smpl_path = "/usr/local/share/SuperCollider/sounds/a11wlk01.wav";

~buf = Buffer.read(s, ~smpl_path);

~in = (mic: 3, pickup: 2, s1: 6, s2: 9, s3: 8, s4: 5, s5: 4, m1: 11, m2: 10, m3: 7);

~tr = ( // trill segment ranges

ntop: [0.01, 0.3104], slide: [0.5171, 0.7242], nbottom: [0.7579, 0.8621],

rimtop: [0.3447, 0.4138], rimbottom: [0.8964, 0.9311],

i2c_bus: 1, i2c_addr: 0x38,

noiseThresh: 30, // int: 5-255 with 255 being the highest noise thresh

prescalerOpt: 1, // int: 0-4 with 0 being the highest sensitivity

);

~jo = {

var strings, mag2, trill, touch0, vstringtop, vstringbottom, smpl, mix;

var buf, bframes, spos;

var t_top, t_bottom, t_mag;

strings = In.ar(~in.pickup, 1);

mag2 = In.ar(~in.m2,1);

trill = TrillCentroids.kr(~tr.i2c_bus, ~tr.i2c_addr, ~tr.noiseThresh, ~tr.prescalerOpt);

// virtual plucked strings on top and bottom of Banjela neck

t_top = (trill[2] > 10) * (trill[1] >= ~tr.ntop[0]) * (trill[1] <= ~tr.ntop[1]);

t_bottom = (trill[2] > 10) * (trill[1] >= ~tr.nbottom[0]) * (trill[1] <= ~tr.nbottom[1]);

touch0 = [Gate.kr(trill[1], t_top), trill[2]]; // pos, size

vstringtop = Resonz.ar(Pluck.ar(PinkNoise.ar, Changed.kr(t_top), 0.2, touch0[0].linexp(~tr.ntop[0], ~tr.ntop[1], 50, 1000).reciprocal, 25.8, 0.5, mul: 6.0), [60, 300,2200], 0.1, 10.0).clip;

touch0 = [Gate.kr(trill[1], t_bottom), trill[2]]; // pos, size

vstringbottom = Resonz.ar(Pluck.ar(PinkNoise.ar, Changed.kr(t_bottom), 0.2, touch0[0].linexp(~tr.nbottom[0], ~tr.nbottom[1], 100, 2000).reciprocal, 20.8, 0.4, mul: 6.0), [90, 1300,3200], 0.1, 10.0).clip;

// mag signal mapping to sample playback

buf = ~buf;

bframes = BufFrames.kr(buf);

mag2 = Lag2.ar(mag2, 0.1).linlin(-0.02, 0.02, -1.0, 1.0);

t_mag = Trig1.kr(mag2.abs > 0.4, 0.1);

mag2 = mag2.abs.explin(0.4, 1, 0.2, 0.05);

spos = EnvGen.ar(Env.new([0, 0, 1], [mag2, 1.0], \lin), t_mag, bframes, 0, BufDur.kr(buf));

smpl = BufRd.ar(1, buf, spos, 0.0, 2);

// Signal Chain

mix = Mix([smpl, vstringtop, vstringbottom, strings]);

mix = Limiter.ar(LeakDC.ar(mix), 1.0, 0.001);

mix * 1.0;

}.play(s, outbus: 0, addAction: \addToTail, fadeTime: 0.01);

Future Thoughts

Well, there’s still a lot of design work to be done. Now that I’ve got a prototype it would be great to make it more sturdy and solid. I’m also beginning to experiment with translating the Banjela extensions over to a standard banjo.. I think the main question there would be mounting of the embedded electronics inside the pot in a way that doesn’t disturb the natural vibrations of the drum skin.

Artistically I’m looking to further explore an extended sonic language for the banjo that carries with it a sense of multi-temporality. Making it possible that the multiple music histories of this instrument can co-exist and perhaps project towards the future. I’m also thinking about how these extended techniques and augmentations could work to making the banjo into a sculptural object - for example, autonomously playing banjos (and other drum or spiked lute-like objects) filling a space, or creating a virtual social communion of sorts.

3 folk songs was the premier performance with the Banjela which took place at IKLECTIK in London, performing with members of the Augmented Instruments Lab and Kuljit Bhamra. A big thank you to all those who supported me at the Centre for Digital Music and elsewhere with great discussions, conceptual and technical support, including: Andrew McPherson, Lia Mice, Laurel Pardue, Dana Immanuel, Duncan Menzies, Giulio Moro, Adán L. Benito Temprano, Giacomo Lepri, Jack Armitage, Charlotte Nordmoen, Francesca Ter-Berg and Fedor Tuinisse. In addition, I want to express extreme gratitude to the Dutch Creative Industries Fund who supported the travel and stay costs of my residency through a development grant.

About Jonathan Reus

Jonathan Reus is a Dutch-American composer-researcher, born in Manhattan NY and thereafter raised in Amsterdam and then Florida, where he became involved in the American folk-art scene. Years later he moved to the Netherlands where he worked at the adventurous performance-technology lab STEIM, developing a uniquely intimate practice cutting across the disciplines of music, performance art, science and digital culture. His work uses collages of technologies past and present to reflect the simultaneous times and histories we inhabit.

He has received commissions as a composer, performer and installation artist by Slagwerk Den Haag, Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, Club Guy & Roni and Asko-Schönberg ensemble. Most recently he composed the music for and built a large-scale tape machine instrument for the nationally-touring production Brave New World 2.0, based on Aldous Huxley’s dystopian novel.

In addition to his artistic work, Jonathan has tirelessly demonstrated his support for local, bottom-up artistic initiatives and novel artist-education formats through curation and community organization. Since 2013 he has worked as a founding member of the non-profit cultural initiative iii in The Hague. From 2015-2019 he organized and curated The Reading Room, at STROOM Den Haag. In 2017 he organized the first Berlin-based Algorave at transmediale festival, along with the performance program The Instrumental Subconscious, showcasing experimental musicians working with self-made instruments. And in 2016 he helped to design the Digital Media bachelors program at Leuphana University’s Center for Digital Cultures, where he won the teaching prize for cross-disciplinary education for his courses on computational literacy through sound and body.

Jonathan is an experienced researcher in the field of electronic music instruments and sonic interaction design. He recieved the W. J. Fulbright fellowship for his work in the research of new digital instruments for music. He has also lectured on the topic of performative sound and technological mediation at academies of art and design, music conservatories and universities.