Scott Myles and the Instrument for the People of Glasgow

"Cycles of energy, sound and optimism"

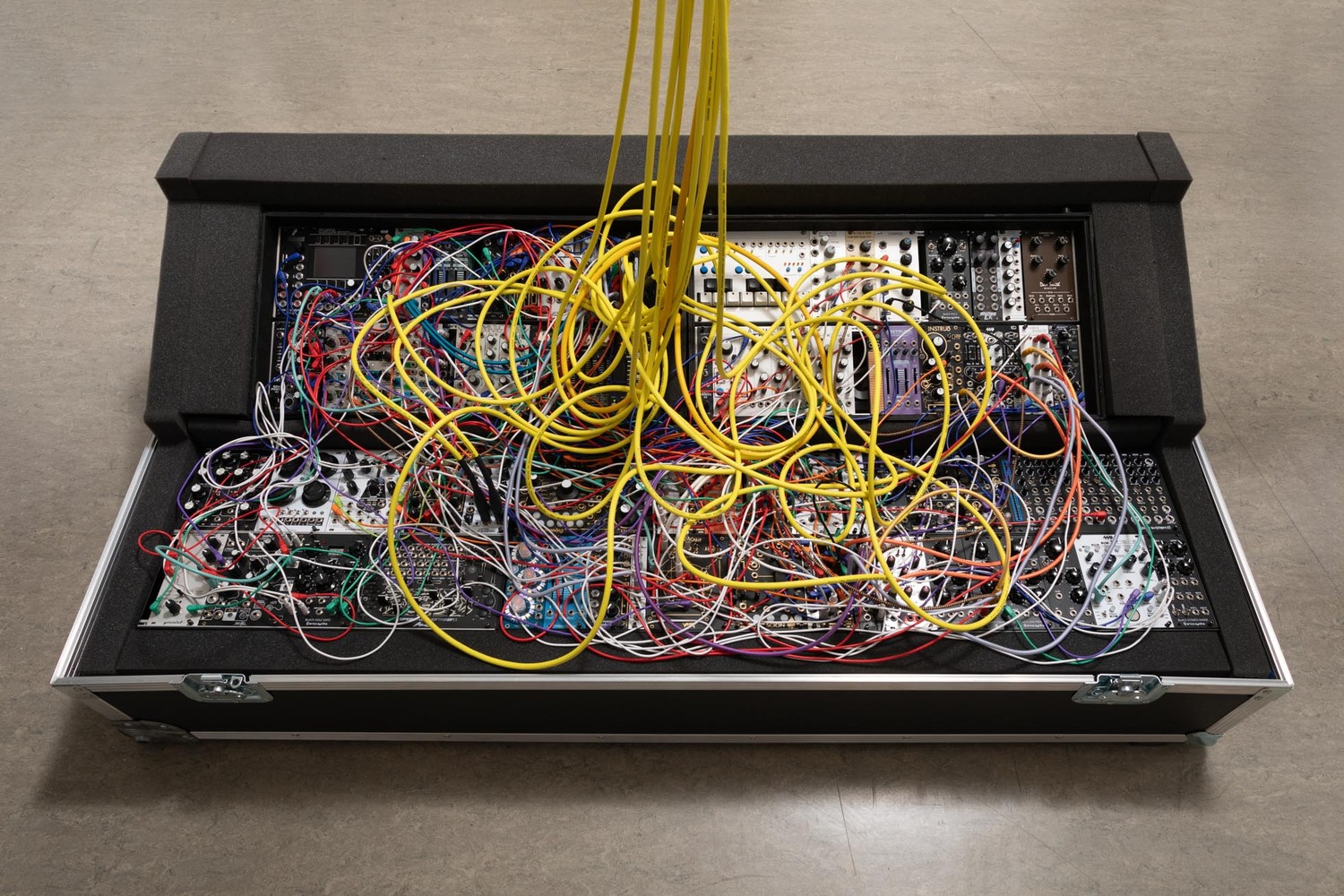

Recent visitors to the Glasgow Gallery of Modern Art (GoMA) found an unusual centrepiece to Scott Myles’ exhibiton Head in a Bell. Amongst prints, sculptures, paintings, sounds and moving images lay the Instrument for the People of Glasgow, a huge modular synthesiser comprimising entirely of modules donated by their respective companies, including our Gliss touch-controller. Despite the through-line linking electricity, human bodily movement, sound and modular synthesis, such large-scale instruments are marked by a problem of access. Instrument for the People of Glasgow addresses this directly. Built itself from donations, the instrument will be donated to the Glasgow Library of Synthesized Sound (GLOSS), becoming something of a public resource and circulating in what Myles calls “cycles of energy, sound and optimism.” We spoke to the Glaswegian artist about the thinking behind the piece and the exhibiton as a whole, and it’s broader implications for economic and politcal organisation.

Your artistic practice often engages with printmaking and sculpture. How did synthesizers enter your creative process, and what drew you to electronic sound as a medium?

The social sculpture is one moment within my practice, I wouldn’t say a culmination, because work is always evolving and themes, mediums recur. But it’s an artwork that’s arisen following many years of my exploring sound as material, and lately I specifically focused on sound synthesis. Getting into synthesis is akin to learning a new language. I like that it’s constructed from many parts, and patched together and interconnected-not unlike the way society functions.

How it fits my interests as an artist is that there are separate modules, that I’ve sourced as donations from all over the world. They’re coming out of a bespoke industry, and when patched together, they generate something powerful and infinite. There’s a live-ness to modular synths, a kind of understanding that things will rarely sound the same, or repeat, and this performative aspect interests me.

During my research I’ve come to conceptually understand something of the landscape of electronic sound. I’ve always loved music, and I use music in the studio to energise me at times, or as a companion. For example, when I play Elaiane Radigue’s Trilogie pieces created on the ARP 2500, I feel a kind of ecstatic presence. I find that droning sonic space a site I can work within for painting, drawing or print for example.

Some of your previous work plays with ideas of authorship, repetition, and gesture. Do you find modular synthesis shares a similar conceptual framework, where patching becomes a form of iteration and transformation?

The modular synthesiser fascinates me because it’s so close to the rawness of electricity, which is of course close to the human body that requires electricity to function. One’s own instrument is a series of decisions, however my project for GoMA was inspired by John Cage’s idea of chance operations. The title of my solo show, Head in a Bell, came from my writing about a photograph of Cage listening to the sound of a bell at a temple in Japan.

As someone with a background in visual and conceptual art, do you think modular synthesis can function as a kind of conceptual practice in itself?

My original idea back in early 2023, was to build the sculpture to be shown within GoMA, and afterwards donate it to Glasgow’s Mitchell Reference Library. The Mitchell reference library has study (carell) rooms that people can rent for small sums of money, to practice playing instruments. For me one elephant in the room around modulator hardware is the cost. I had the idea that it could be interesting to build an instrument from free donations, and donate the sculpture to the Mitchell Library, whereby anyone interested in playing and experimenting with the instrument could access it free of charge by borrowing it within the library. I think of my action of asking a little, from a lot of people as an egalitarian model of economic organisation. My artistic strategy is applicable to other contexts and scenarios, for example politics.

Have you explored DIY or custom instrument design?

At one stage several years ago, I bought a soldering iron, and was learning about the components that are assembled within hardware modules and synthesisers. Frankly though, it felt a bit overwhelming. A helpful introduction and access point to understand sound synthesis modules from a technical perspective though. I find the side and back view of each module as exciting as the faceplate! In hindsight, I think I’ve been trying to learn about modular synthesis because it fascinates me as a symbol of potentiality. A cheaper way to engage in sound experimentation would be via software plugins and the like. I think I was trying to get closer to the source though i.e. electricity. Something very alive.

“Instrument for the People of Glasgow” is described as a ‘social sculpture’ comprised entirely of donated Eurorack synthesizer modules. Could you elaborate on the process of gathering these donations and how this collective effort influenced the project’s development?

In terms of real-time; I created the Instrument for the People of Glasgow sculpture using donations from companies I approached in Berlin, first visiting Superbooth in May 2023. I handed out letters to the exhibitors and had many great conversations - with Bela for example! The first person to say yes was Girts from Erica, and the last donated modules arrived last summer (2024) from Andreas at Schneidersladen in Berlin. For over a year small boxes arrived at my studio containing small and beautiful electronic modules, speakers and other tools from many countries around the world. My artwork could not have existed without the generosity of all the companies who donated.

In the same way the modular thing is comprised of many individuals making up a collective scene, my show also involved collaboration, and community. The full list of contributors are listed on the museum wall, and I designed and printed 22,000 posters with designer Daphne Correll that picture all donations. The poster is freely available to take away from my installation during the 7 month run of my exhibition. Back in 2009, I titled an artwork of mine ‘social sculpture’ when I made a solo show in Cologne. My sculpture back then was a nod to artist Joseph Beuys’s attempt at combining art with politics. The phrase “social sculpture” is a phrase used to describe an expanded concept of art and was invented by Beuys, who was a founding member of the German Green Party. The term embodies an understanding that art can transform society - something I really believe in.

The instrument processes live audio feeds from GoMA’s air circulation system. What inspired you to incorporate the building’s ambient sounds into the synthesizer, and how do you feel this integration affects the visitor’s experience of the exhibition? And why the air?

I was invited to make a solo exhibition in Gallery 3 at GoMA. As my ideas developed, and the idea of presenting my sculpture in the space grew, I became aware of a sound already present in the gallery spaces. This sound in Gallery 3 emanates from an out-of-sight air exchange handling system that sucks air out of the space and sends fresh air from GoMA’s plant room back in. I collaborated with another artist Oscar Prentice Middleton to produce the sound aspect of the installation. Over a year we’d meet in my Glasgow studio, building up the instrument, experimenting and talking about what we might do. Our collaborative piece is called Air is Moving and involves us taking the Instrument for the People of Glasgow and micing up GoMA’s plant room. Cables bring the signals down to the instrument and over the course of seven months a live sound feed is presented.

It’s a modified version of the Museum itself, the shifts in climate and the exchange of air in the galleries. Accompanying the sounds are other artworks: a large painting titled Able Inhaled (an anagram of ‘Head in a Bell’) depicting the unseen plant room. The viewer might perceive similar systems at play throughout my show and collaborations. Air enters and leaves the galleries, literally facilitating and mimicking breathing. The modules are circulating too-they’ve come into my ownership, but only temporarily. Hopefully viewers perceive these cycles of energy, sound and optimism, all present within the space.

You’ve mentioned plans to donate the instrument to the Glasgow Library of Synthesized Sound (GLOSS) after the exhibition concludes. How do you envision this transition impacting the community, and what role do you hope the instrument will play within GLOSS?

I was speaking to people about what I hoped to do, and learned about ITEM workshops, which is a project by musicians Lewis and Suzi Cook from the band Free Love here in Glasgow. GLOSS is a community interest company that has just started up in Glasgow, and is the first electronic music library in the UK. I met with Lewis, and decided that GLOSS should be the destination for my sculpture, once the exhibition at GoMA closed. The instrument will be available via this non-profit, artist-led and community based organisation. They’ll be able to provide access to the instrument as part of their activities with education, workshops, performances etc. Of course, my hope is that I can re-present the sculpture in another location in future, leading to new collaborations and sounds. I’ve actually just been approached by Greenpeace at Glastonbury, and we’re discussing if the instrument can go down there, and a new project can be initiated. I like the idea of the flight case losing or accruing modules, and accumulating signs of use. Perhaps it resurfaces in 20 years within another installation of my work. Instrument for the People of (insert your location here)! That would be a wonderful thing.

To learn more about the Glasgow Library of Synthesized Sound visit their website: https://www.gloss.scot/.