Studio Olafur Eliasson and Bela

"Seeing yourself seeing"

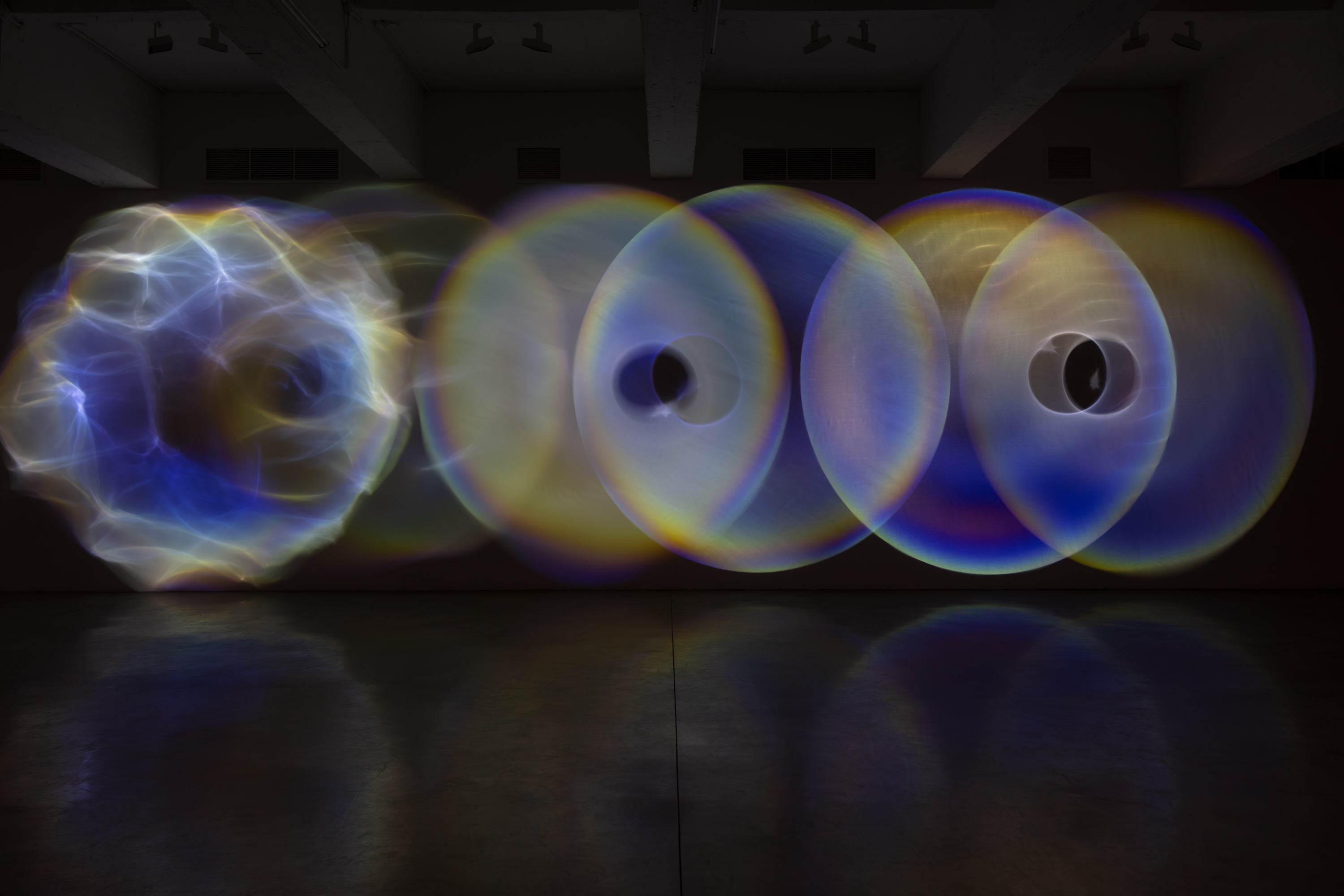

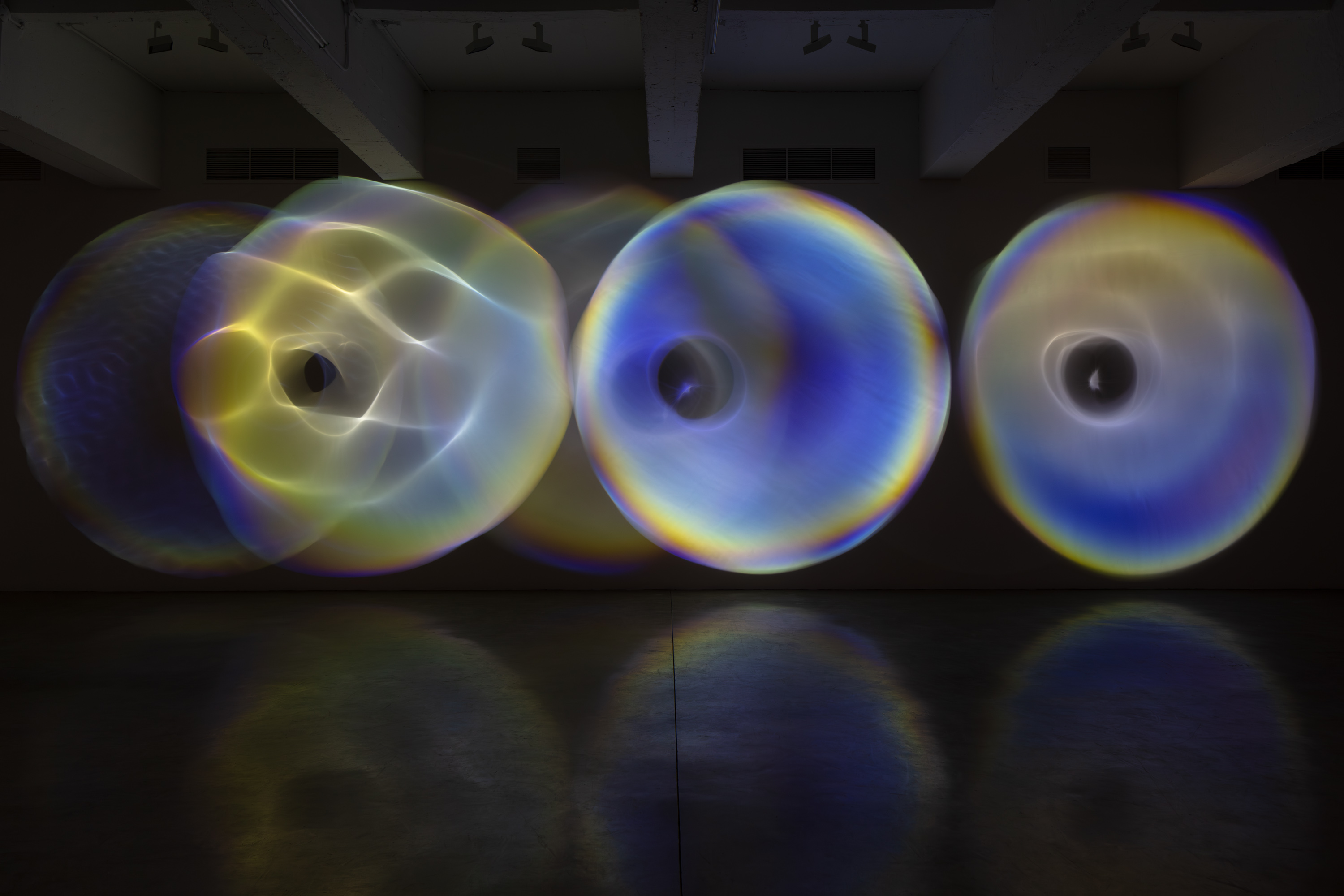

Olafur Eliasson’s installation Your psychoacoustic light ensemble premiered at Tanya Bonakdar Gallery in New York in summer 2024. It was a looping, generative sound and light work built from scratch by Eliasson’s studio team using mirrored foil, sine tones, directional speakers, multichannel audio, transducers, DMX lighting, and Bela running Pure Data, and was one of the gallery’s most attended shows to date.

For this interview, we spoke with two key contributors to Your psychoacoustic light ensemble: longtime studio head Matt Willard, who has been with Studio Olafur Eliasson since 2004, and Brazilian composer and sound artist Ananda Costa, who led the installation’s audio integration using Bela. Though Eliasson is often described as a “light artist” (he filled the Tate’s turbine hall with an artificial sun in 2003), his Berlin-based studio functions more like a collaborative lab, integrating dozens of people working across architecture, sculpture, science, engineering and sound. Here Matt and Ananda discuss how the studio has built its own sound vocabulary, the cost (and limitations) of directional audio, and what it means to balance Bach with sine waves.

Tell us a little bit about your background and how you started out working here.

Matt Willard: I’ve been working for Olafur since 2004. It was a much smaller studio then. I had just moved from New York where I had been doing art production and museum work. I also had a small audio practice.

Really? Did you go to art school?

MW: No, I studied cultural anthropology with a focus on ethnomusicology in Austin, Texas. I moved to New York to continue ethnomusicology at CUNY, planning to study salsa in the city. But I ended up in the art world, working with sound artists. A friend and I had a little studio in Manhattan helping artists with sound work and recording improvised music. We had a gallery space next door. People came to use the reverb in the room instead of adding it digitally. We were using a Digi-001 interface and some inexpensive Russian mics, but it worked.

Ananda Costa: I’m a composer and sound artist from Salvador, Brazil. I studied music in Brazil. I moved to Berlin to research the theremin, and started studying different theremin players and their teaching methods. I didn’t plan to stay in Berlin, but then I came to the studio here as an intern in the research department doing support for Olafur’s artwork Research Map. Then the sound group formed and I happened to be there at the right moment. Nick, our sound designer, left for Iceland, and I stayed on. That was two years ago.

I compose all kinds of music: pop, soundtracks, ambient. I sing, perform, and have released albums. I’m trying to focus more on ambient music now. But I do too many unrelated things.

Matt Willard and Ananda Costa.

Can you give us a sense of the studio structure here? How many departments are there, and how does it all come together?

MW: Art making here overlaps with multiple disciplines, including architecture under Sebastian Behmann. The production team handles everything from watercolor and glass to oil painting, electronics, and woodworking. We also have a machine shop, glass and electric workshops, and a big metal workshop offsite.

There’s also public commissions, architectural pavilions–big projects like Fjordenhus in Vejle, Denmark and a virtual/digital department too, called Digital Body. Right now, that’s a small two-person team focused on multimedia and VR.

Then there’s the archive, finance, the kitchen–we eat together three days a week—communications, exhibition design, research and development, and IT. Olafur meets with team leads and sketches out ideas, which turn into prototypes until something gets made. It’s sort of a playground or experiment. For a long time, like in the sound team, we were just doing that.

As the sound team is kind of independent, it doesn’t clearly fit into a structure. Naturally, this led to some growing pains.

AC: The sound group came out of the Garden, the ground-floor space here. It’s meant as a place to experiment without needing a finished product. That’s where we began–just meetings, listening sessions, testing ideas.

MW: We had invited some guests, friends of Olafur’s from Iceland to come for a weekend workshop. In an extended weekend, we recreated the history of sound art by going through a series of experiments with piano string, piano wire, magnetic pickups attached, solenoids hitting objects. We all know that stuff, but we had to go through it to get on the same page about where we are and what we want to do.

So you had to develop a sound identity for Olafur Eliason’s studio from the ground up?

MW: Yeah. Olafur is a visual artist, known really as a light artist. He’s dabbled in sound before–there was a 2008 piece at Tanya Bonakdar Gallery in New York, which was a drawing machine based on a single string instrument. But Olafur is also a musician and plays guitar and was always drawn to music. But the vocabulary around sound here was still very visual. People talked about “beams of sound,” like light. That eventually led us to directional sound.

AC: We weren’t trying to innovate for the sake of it; it was more poetic curiosity. We experimented with directional speakers, theremins, foil, transducers, mirrors, wind, sounds of leaves–a lot of visual-sound crossovers. Just indulging. We even tried to get people’s attention from the rooftop with directional speakers.

MW: At some point, we started looking into Holoplot. We were trying to sort of recreate a really simple system because people kept using the light reference. They wanted to “shoot a beam of sound” but we were convinced it doesn’t work that way. Then we met Holoplot and they said it can work that way.

AC: But we had a content problem. We realized that while the tech worked, the question remained: what’s the content? That’s where things got complicated. I composed hours of test tracks with different instruments and approaches–just trying to see what stuck.

Did that content challenge carry into the installation Your psychoacoustic light ensemble at the Tanya Banakdar gallery in New York?

AC: Maybe it’s easier to talk about the process. Originally, it was about how to manipulate a viewer’s reflection using sound. That didn’t work quite as we expected. We were trying to get standing wave patterns projected using a theremin and a transducer on a shaking mirror. Eventually, we shifted to microphones and explored Chladni patterns. Once the New York show was confirmed, things accelerated. We didn’t know how many channels we needed, so we ordered as many Bela boards as we could get, the big ones with multi-channel capabilities. We thought it might be a 32-channel installation or several six-channel units. We knew we wanted light control too, so we started building a system that combined DMX and audio.

So Bela and Pure Data became central to the project?

AC: Yes. When the sound group started, Nick made a starter kit list, and Bela was on it. I had learned Pure Data in school and it made sense to go that route. Bela was compact, stable, and didn’t require starting up a Mac Mini or Ableton session. For installation work, you need something that just runs.

MW: We were also dealing with a studio renovation, moving between buildings, testing setups in storage rooms. It was very nomadic. We were always in the way.

AC: The Bela setup made it easier. It boots directly, no GUI, no extras. We also integrated DMX lighting via Arduino, using serial communication with Pure Data. It wasn’t the most elegant solution, but it worked quickly. In the end, we created a fully expandable system, even if we didn’t use every feature.

How much did the tech shape and support the content? Or did the ideas shape the technical decisions?

AC: Well, we had to translate Olafur’s idea for a sound work. We are essentially translators and are always trying to anticipate his ideas. It’s like composing. You can have ideas, but the instrument you write for changes how those ideas manifest. With tech, it’s the same. We knew we wanted sine waves for generating visible Chladni patterns. Everything else followed from that. We had lots of conversations: do we want this to be generative? Do we want it to be a composition? Do we want it to be something that is not musical at all–just sound without any kind of melody or harmony?

MW: What was unusual was how the piece grew. The work drove the creativity, not the other way around. Accidents in setup would yield unexpected results. We’d go down a path, and Olafur might steer us somewhere else–sometimes into Bach.

AC: I think an interesting or funny moment would be when we were really into visualizing beats between sound waves and we were trying to go really like the most extreme possible beat, like 0.001 difference in two sine waves so we would see the whole developmental thing and Olafur comes here and he wants to listen to Bach. There we are doing this super mathematical composition thing and we were like, what do we do now? It was a lot about understanding how to combine Bach with this more technical thing that for us was really interesting and beautiful. But sometimes the most interesting, beautiful math-related sine wave approach didn’t sound great. Bach sounds great but didn’t always visually produce the best results. So it was always trying to balance these two things: what looks good and what sounds good. And it was clear Olafur wanted music.

MW: We had mirrored foil stretched over a frame, with a transducer playing a sine wave. But because of the nature of the mirror, the timbre was so affected. So you had a sound of a cello. It really became this beautiful sound out of a sine wave. A guy came to document the show and he said “Just send me the audio tracks.” And we’re like: it’s just sine waves. And we saw him make the connection–that the audio track is the one in the room right now.

AC: It’s the sound of the mirrors in that room and it sounds in a particular way. When we try to get the soundtrack from Pure Data, it doesn’t quite work.

So you essentially built instruments?

MW: Yes, we built a speaker system to reflect the sound in the purest way possible. It was funny when Ananda sent the audio files to me and the photograph of the waveforms. It’s just like caterpillars and sine waves.

Was ambient music part of your thinking?

AC: Definitely. I love ambient music, and it aligns with Olafur’s work–slow, contemplative, open. It leaves space for you to interpret. It’s not happy or sad; it lets you decide. That openness mirrors how people engage with his visual work. It’s not background music. Ambient asks you to be present. It doesn’t induce feelings; it reflects them, like a mirror. And mirrors are literally part of our installation.

What was the starting point conceptually for the New York show?

MW: Seeing yourself seeing. That’s a recurring theme for Olafur. We wanted sound to manipulate the viewer’s reflection. But technically, it didn’t quite translate. So we went back to experimenting with mirrors, sine waves, projections and motion. Nothing was fixed. We just knew we needed flexibility–and we over-prepared. We brought everything.

And what came out of that?

AC: A 32-second looping composition made in 24 hours. Olafur wanted a finished piece at the last minute. We reduced everything down to six frequencies–one per instrument. I created generative elements and synchronized DMX lighting to amplitude. It was an intense process, but it worked. People thought it was a five-minute piece. It just looped so seamlessly.

MW: It helped that the visuals distracted from the loop–the mirrors shaking, lights moving, the physical presence of the sound. Visitors became part of the piece. It was one of the gallery’s best-attended shows. Long lines. Great press. Very rewarding. We spent the summer in a dark room, barely seeing daylight. Sleep-deprived, caffeinated. Also, when no viewers were in the gallery, I wanted the sound off. We wanted to put motion detectors in the room and in the entrance, so we would know if somebody’s present.

AC: One night, trying to implement motion detectors to turn off the sound, nothing worked. I was convinced my career was over. But in the end, the gallery staff said, “Just leave the sound on. We like it.” Looking back, we built instruments. Not just transducers, but whole systems that transform space. Mirrored foil, sine waves, transducers–it made sine tones sound like cello. We documented everything. The studio has a huge archive of Pure Data patches. None of it is lost.

MW: And all the hardware was off-the-shelf. Lighting stands, basic mounts. We didn’t even know the budget until afterward. No one told us to stop. We just made the thing we had to make.