Krzysztof Cybulski on Instrument Design

Interview with the Polish artist about his work and latest instruments

Creating new electronic instruments requires a delicate balance of technical expertise, craftsmanship and musical understanding. In this blog post we interview Krzysztof Cybulski who strikes a perfect balance between these 3 elements in the instruments he creates. We talk about the scene in Warsaw, his latest instruments and the tools he couldn’t work without.

The acoustic-mechanical-pneumatic

Hello Krzysztof, you first came onto our radar through your work with the brilliant Polish new media arts collective, panGenerator. Can you tell us about your practice and approach to instrument design and how it relates to your work as part of the collective?

panGenerator has been around for more than 12 years now, and creating some 30 projects with the guys has been a large part of my professional and artistic life, as you can imagine. Nevertheless, I‘ve always tried to maintain my separate, solo path, as some of my ideas and objectives aren’t exactly in line with panGenerator style, which I believe we’ve managed to maintain over the years.

Modular Process Music is a concept / set of instruments designed by Krzysztof to create improvised music in a new way.

In my solo work I focus on the functional aspect of the instruments and sound objects I’m building, although I have some idées fixes which probably make the matters more complicated than they should be. For example, It’s not difficult to carry out the spectral resynthesis of the human voice in real time in the digital domain, but it’s been done many times, so my own take on the idea had to be in a form of acoustic-mechanical-pneumatic device, because I must hate myself ;-D. I’m definitely preoccupied with the very process of sound and music creation, as well as the performative aspect of music. Another element is the focus on acoustic sound sources and traditional or even obsolete technologies, but seen from a contemporary perspective.

I’m not that focused on the design aspect of things I’m building, although I certainly want them to look good, but usually the final outcome is a combination of what I want aesthetically and how far I’m willing to stretch myself in terms of fabrication effort ;-).

You are working towards a PhD at the Chopin University of Music in Warsaw, how is the scene for experimental arts and technology there?

The university itself is a large institution, thus it has certain inertia against changes, and the department structure doesn’t necessarily reflect the reality and dynamics of contemporary music scene in Poland, but luckily there’s a number of people at the university who are progressive thinkers and doers. There’s CUEMS (Chopin University Electronic Music Studio) which organises cyclical electronic/new music concerts, which gather large, enthusiastic audiences. A lot is going on in terms of interesting interdisciplinary projects at the sound directing department, also a lot of experimentation (including some instrument building) takes place at the percussion department. They’re definitely opening up towards a more experimental approach to music.

A collage of images from one of panGenerators previous shows from 2020, ICONS. Krzysztof has been collaborating with panGenerator for 12 years now. Check out our previous blog post on ICONS: blog.bela.io/icons-by-pangenerator

As of Warsaw itself, it has a large and exciting experimental music scene, spanning a broad spectrum from contemporary composition, through experimental electronic, improvised music, to experimental jazz and rock; the boundaries between these categories are blurring, which is a fascinating process to watch and to be a part of. There aren’t many experimental instrument builders that I know of, though.

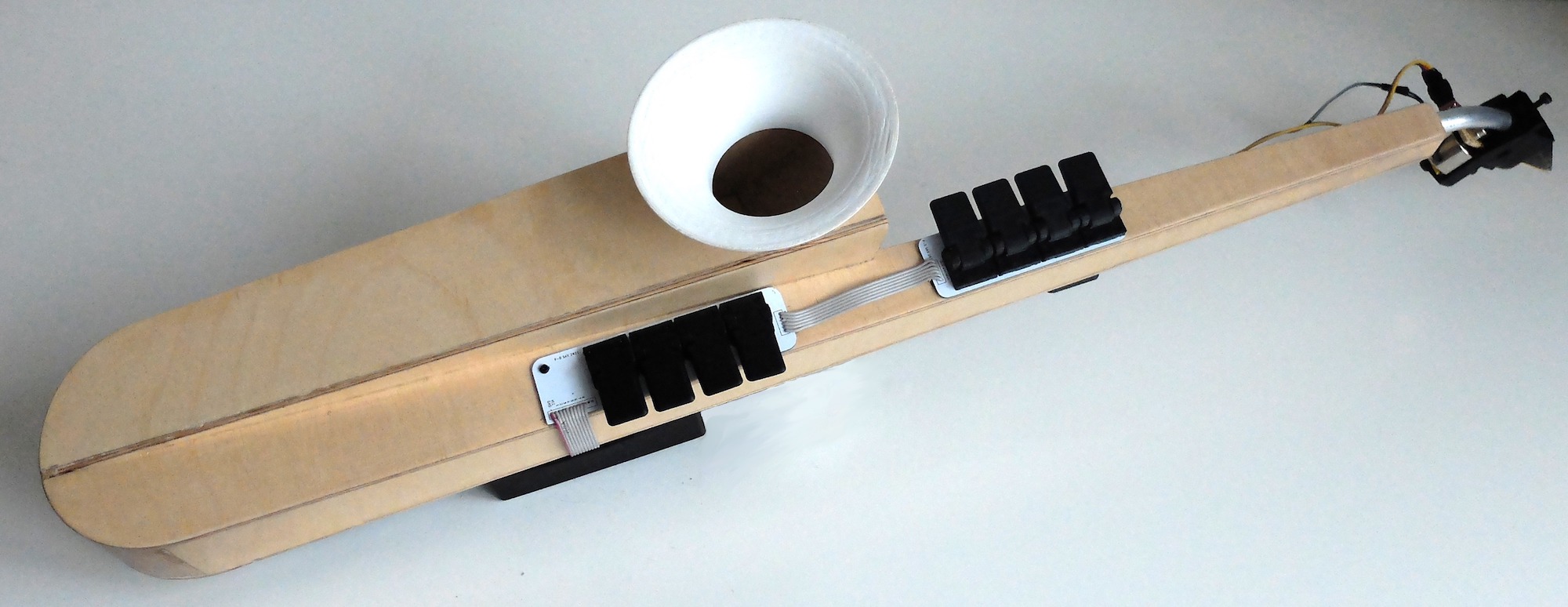

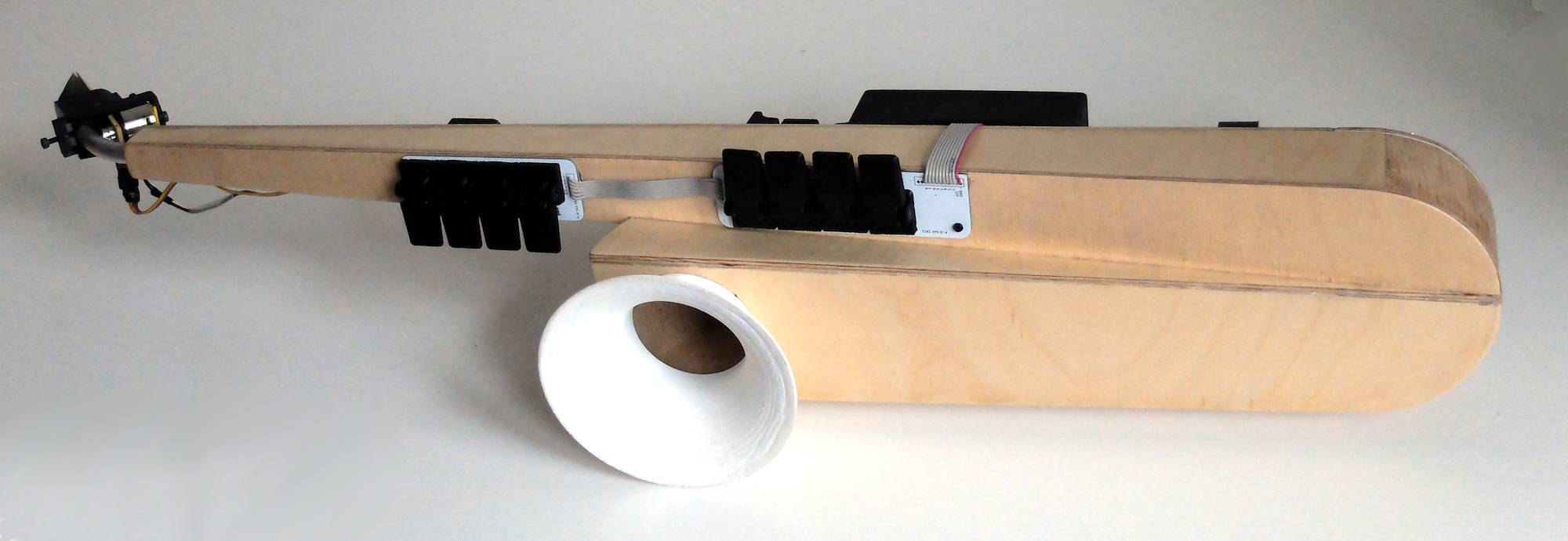

One of your latest instruments is the Post-digital Sax which you describe as a hybrid acoustic-digital instrument. Can you tell us a bit about the sax and your inspiration for building it?

It’s hard for me to track down the direct inspiration, but the main principle of operation is based on the general way in which the sound is produced in single-reed woodwind instruments. There are basically three necessary components to produce the sound: the air from the musician’s lungs, an elastic slice of wood known as the reed and a resonating air column residing inside the instrument’s pipe.

My idea was to remove the third element out of the equation and force the reed to vibrate at arbitrary frequency by the means of an electromagnet. Then, I thought, you could send a digitally controlled alternating electrical current to the electromagnet, and this way you should be able to control the pitch of the sound by digital means, while preserving the ability to influence the volume and timbre of the sound with breath and embouchure. When it came to prototyping, it wasn’t that difficult to get the reed to vibrate, but it required a lot of fine-tuning to actually build a playable mouthpiece. All in all, it took three major prototypes and a number of revisions of individual elements to get the current version of the instrument, which is now fully playable and can be considered an acoustic instrument, at least in terms of how the sound is created (no speakers whatsoever).

As for the digital aspect, I’m only starting to explore the possibilities - apart from the obvious ones, like various mappings of the instrument’s keywork to different musical scales, many different interventions and alterations are possible, like those known only from electronic or digital instruments - phrase looping, arpeggiator and such. Of course, you could always use an external microphone and digital delay/looper to transform the sound of an acoustic saxophone, but in the P-D Sax you could repeat the phrase in terms of musical notes, while still preserving the ability to influence the timbre and volume. Eventually the instrument will be a part of a small ensemble of similar, digitally controlled acoustic instruments.

We can’t wait to see the full ensemble! And so technically, what’s inside of the P-D Sax?

There’s a Bela Mini, obviously, which runs a relatively simple Pure Data patch - at least in terms of the audio it produces - it’s really just a monophonic pulse wave. More important for me was the possibility to analyse the audio input, so the instrument could listen to its surroundings and adapt to it in various ways.

Apart from Bela, there’s the electromagnetic mouthpiece, the keys with continuous action, making use of hall sensors and small permanent magnets to sense the keys’ position, and a small thumb-controlled joystick to modify the phrase looping feature. As Bela has only 8 analog inputs, I’m using a Teensy board, functioning as a midi device, for additional analog signals from the joystick. It’s rather simple, but the trick to make it work was to fine-tune a number of small nuances. For more technical information check out this NIME 2022 paper.

You’ve been building instruments for a long time now. When did you first come across Bela and how did it fit into your practice? How do you use it now?

I don’t really recall a particular moment in time, although Bela was definitely something I was looking forward to. For a long time I wanted something which wasn’t a laptop but could run Pure Data patches (or patches built in any other environment, for that matter). The first device of this kind which I’m aware of was the Nord Modular, then there was nothing new for a long time, and all of a sudden this kind of embedded-computer style devices started popping out one after another. First there was the Axoloti, then the Owl, Organelle, and then PiSound and Bela came to my attention around the same time, which was probably some five years ago.

Memo/move in the above video is part of the Modular Process Music project and also features a Bela Mini inside for audio processing.

For me Bela, and especially Bela Mini has the perfect level of openness: you can use it almost instantly by running example patches from the Bela IDE, but it doesn’t dictate any particular usage scenario or form factor: no fixed pots or audio inputs/outputs, but if you want any pots or other sensors, you just attach them to the board Arduino-style and their signal is readily available inside a PD patch in a form of additional adc’s. It’s brilliant, really. The only thing I struggled with in the past was the issue with FFT based modules, like fiddle~ and sigmund~, which I tend to use a lot - they’ve caused a large number of drops in the audio thread - but it has now been largely resolved (Giulio Moro has been very responsive to the issue reports on the Bela forum and really dedicated himself to resolving them). Also the extended range of buffer sizes helps a lot if you’re using these modules extensively and your particular patch can deal with slightly larger latency.

What is favourite tool (physical or digital) which you couldn’t work without?

As you’ve probably noticed already, I’m addicted to Pure Data and - well - it would be really hard for me if it wasn’t around. PD runs on just about anything, and even though its interface is a bit austere, it’s really a great tool. Although I know my way around writing basic code (which is a necessity when you’re using Arduino or Teensy), it’s much easier for me to think in patches than in code - probably a common trait in people with musical background - the data-flow programming metaphor seems just more natural when you’ve had experience with modular synths, or even just guitar stomp boxes.

Do you have any particular favourites from the instruments you have created in past?

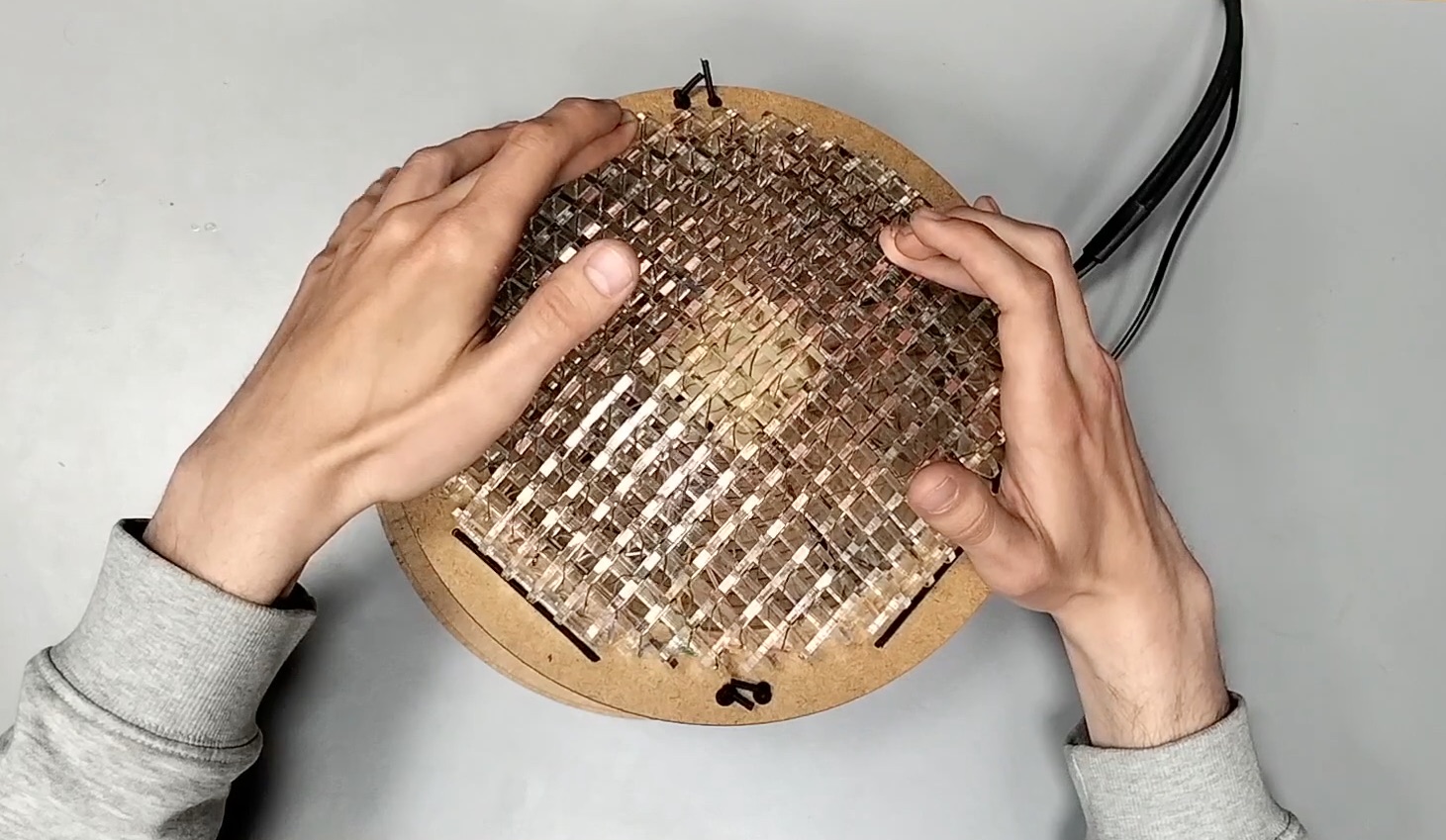

I think that would be the Acoustic Additive Synth, which builds upon the idea of spectral resynthesis, but in a physical, acoustic form. I like how it combines the centuries-old techniques of organ and bellows building with a modern implementation of the Fast Fourier Transform, microcontrollers, servomechanisms and digitally fabricated mechanical parts.

Some of the design problems had to be resolved with a combination of modern and traditional approaches, like the proportional air valves for each of the pipes - the resulting mechanism consisted of a crossbreed between the organ curtain valve and Rolamite, operated by a RC servo - a quirky little device, really, which proved to be a perfect solution. Similarly, the servo-controlled swanee whistle-inspired pipes were a mix of old and new, which worked out just right. It all summed up to a device which could be used both as an instrument and an interactive installation, and the sensation of hearing glimpses of recognisable vowels in the combined sound of a couple of acoustic pipes is really thrilling (how come, no speakers?)

And finally you have any advice for someone wanting to get started with instrument building and new media art more generally?

I think if somebody has an urge to get into any of these areas, he/she is already half way there - the basis of this business is a deep interest in the very matter of it. Even if you just spend time browsing through videos of various instruments, installations and such, you’re gradually building a sense of what’s possible and what can be done with today’s technology, and that’s a great starting point. Obviously, there’s a considerable amount of craftsmanship involved, so it’s advisable to take a basic course of Arduino / Pure Data / soldering / digital fabrication / woodworking etc., which luckily can be mostly learned from free online resources these days. The most important part is to try and make as many projects as possible - this is where you learn the most, really. If you’re almost done with your prototype, but there are some issues stopping you from completing it, it’s the strongest motivation to learn something new ;-)

A huge thank you to Krzysztof for agreeing to this interview and for his generosity in sharing his work. To find out more about his work visit his site. Top photograph of Krzysztof was taken by Mikolaj Zajac.